«we position ourselves to be real ignorant but in turn this motivates us to get out of this ignorance»

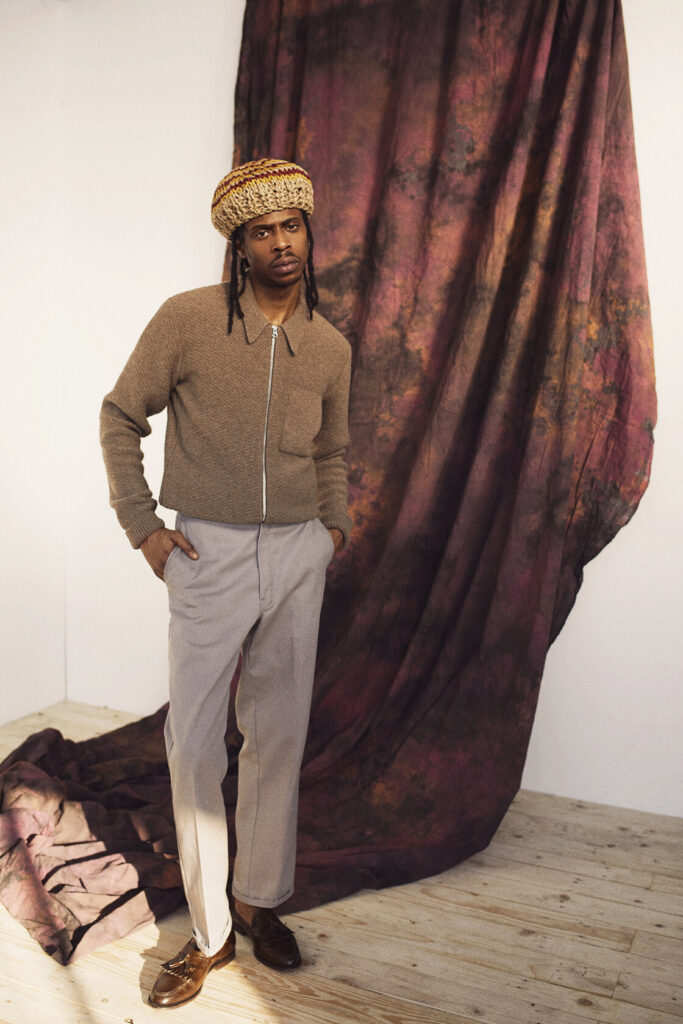

Formafantasma, led by Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, is an Amsterdam-based design studio that focuses on investigating the ecological and political responsibilities of their discipline. By placing research at the core of their practice, they create a holistic approach that aims to reach back into the historical context of material used by humans, and outwards to the patterns of supply chains that have been constructed to support and expand its use. Formafantasma’s work often investigates material’s effects on the biosphere and their survival in relation to human consumption.

NR had the pleasure to speak to Andrea and Simone for this issue. The conversation explored their practice’s journey thus far, the processes behind the research and commercial sides of their practice, and what they’re looking forward to in the future. They spoke in depth about designers responsibilities to understand the impact of the materials they use, and that they should be more transparent about the impact of their work. The duo placed emphasis how the lack of communication between practices, corporations and consumers often prevents meaningful large-scale changes to shift the industry towards a more sustainable future, and highlighted the role that designers can play in facilitating better communication in this process. Our talk also covered the Geo-Design masters course the pair currently lead at the Design Academy Eindhoven, which started its first academic year this year.

Andrea and Simone it’s a pleasure to have you with us today and thank you for this opportunity to have this conversation with you. I want to start by asking you about how you met and your journey together as Formafantasma so far.

Simone Farresin: Me and Andrea met in Florence during our bachelors studies. Andrea is younger than me and he really cares to say that. I was in my final year and I was starting to lose interest in design in terms of product design and object based design. When we started to hang out we were looking at many other things. We were going to art exhibitions together, we were traveling around in Italy checking out things we were both interested in. We started living together and realized most of our conversations were design related.

Andrea Trimarchi: And he was helping me throughout my projects. So we started to work together on projects, starting mostly with ones related to graphic rather than product design, which was quite fun because it was something we were doing in our free time. We decided to make this into a more programmatic experience, and while this process was happening we decided to apply to Eindhoven together. Strangely enough we applied with one portfolio for both of us, so the only way to take us was as a duo. And of course we were really interested in what was happening in design in the Netherlands, specially at Eindhoven, because there was an entire generation that were our generation that had studios there, and had created a community around the design field.

SF: It was different in Italy were although there was a fantastic history in design that continues till today, nevertheless the heritage from the past felt extremely heavy. And the Dutch have a tendency of looking forward instead of looking back. This was a reason were we wanted to come here, and its been an extremely informative period. Specially our time in the Design Academy (Eindhoven) were we always say that we received just the questions we needed. We were full of energy and potentiality, but we didn’t know were to channel that, and in the design academy the questions were raised were extremely critical, and in Dutch fashion quite brutal at times. Nevertheless it was invaluable experience because we were asked existential questions for designers rather than focusing just on how something is produced. For example “Why would you produce this in this moment in time?”, “How does it relate to the past development of the design discipline?” and “Where do you position yourself in the world as a designer?”. Although these questions can be overpowering for some, we felt that they were empowering us and encouraged us to establish an agency, and therefore became quite formative for us.

AT: And it really prepared us to the extent that the day after we graduated we opened our studio, and we started Formafantasma and so on.

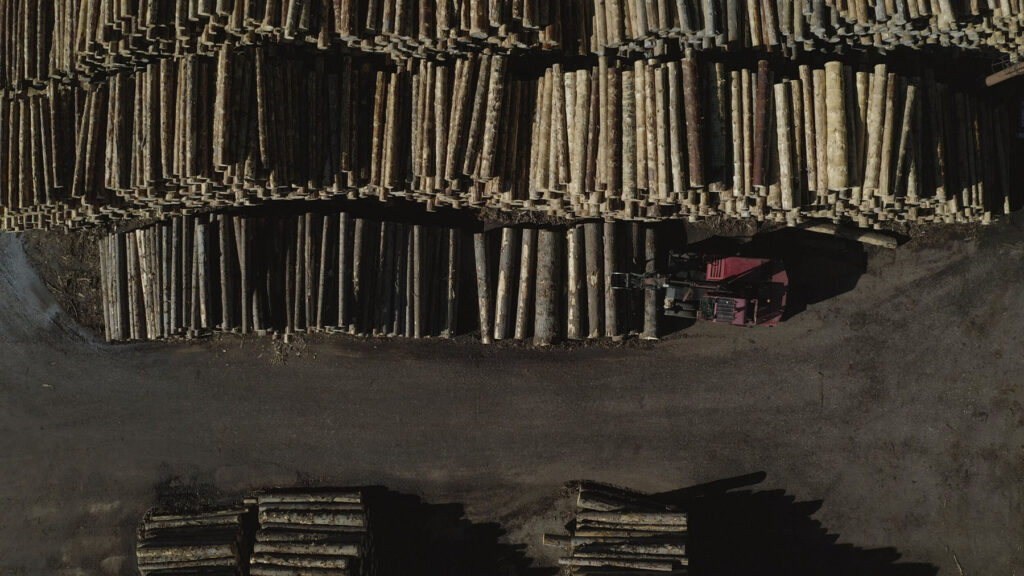

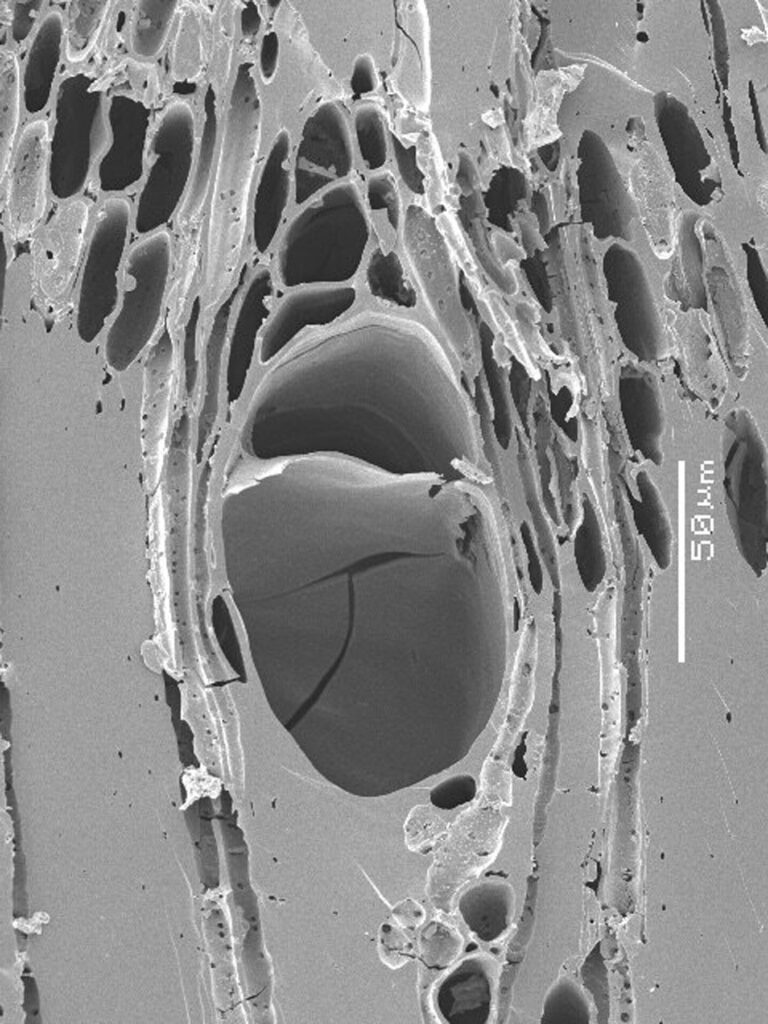

I realize that its the 11th year anniversary of your studio so congratulations on that. As an aspiring designer it’s quite informative to look at your progression throughout these years, and how you’ve managed to position the research and commercial sides of your practice in a way that they inform each other. My most recent experience of your work was Cambio (Serpentine Galleries, London), and the project focuses on the use of wood as a material in the industry, and the impact it has on the environment. To me this project highlights the emphasis you place on reaching across different disciplines, and engaging with a variety of practitioners in your research development process. Can you explain why this outreach is vital to this process, and what quality it brings to your research driven work?

SF: I think it’s because when we look at the macro picture within which design preforms it becomes inevitably vital to reach out to other practitioners outside of our field to understand that macro view better. We are more and more interested in looking at design as not only a means to deliver services and products, but rather looking at design in a much bigger infrastructure. Which in relation to materials includes resourcing, distribution, refinement, transformation, recycling and so on. When you start to look at design within this broader system you can begin to question what design can do and cannot do, and in this process reaching out to other practitioners is a way to better understand the implication and consequences of design.

AT: Also because there is this big narrative that design can solve problems, and in a way it can. But it is important to acknowledge that it’s also true that it can’t simply because we don’t know a lot of things, and the only way of acting on this is to reach out to people that are much more informed than us. So in a way we position ourselves to be real ignorant but in turn this motivates us to get out of this ignorance.

While going through Cambio and the series of interviews you conducted, one of the things that resonated with me is that it was felt in some way that your interest in these ecological issues is driven by the consequences of being designers. This idea that a sense of responsibility transcends into establishing a holistic approach throughout your practice. To further understand this dynamic, what outcomes do you aim to achieve from your research driven work? and what is your process of reaching out to your partnerships to input this research into practice?

AT: Firstly I want to say something, I believe a problem within design is that it is complicit in a way in the disaster we are witnessing. This in turn makes the discipline quite interesting, and whatever we do that is not perfect it can’t be perfect because it sits between exploitation and the destruction of the world. It is in this liminal position were we see all things happening.

AT & ST: Potentiality and also disaster.

SF: Some of the projects we’ve done recently, for example Cambio and Ore Streams, are good models to display our way of operating when we do research. For us it is a way to present ourselves with an expertise that not necessarily people think we have. What I mean by this is that in a way these projects are responses to the questions we never receive from our partners.

The questions we pose ourselves when we develop those projects are the questions we would wish to receive, and the challenges we would wish to be asked. But we are using this to show that we hope that the conversations we have with our more commercial partners , and partners in general, can grow in this direction. I think the more people get to know us, the more the questions we receive become sharper and pertinent for what we can do. Of course it is still a struggle because the infrastructure we were talking about before is not necessarily easy to penetrate, so even when you work with a partner, that does not mean that partner can make a change in that system even if they show willingness to. Nevertheless we always know that there is plenty that you can do as long as you accept the limitations of your own discipline.

AT: I want to add that while in Ore Streams it was much more difficult to get in contact for instance with electronic companies, with Cambio it made a complete difference because it was much more possible from a design perspective in terms of design companies. For instance, right now we are in discussion with a company that we are essentially continuing Cambio as an internal RND (Research and Development) were we are trying to apply the same ideas we discussed in Cambio within the industrial production realm. Even if a percentage of our research would be re-applied in this context we would be in any case really happy. We are beginning to see this shift in mentality.

Companies are starting to approach us because of the ways in which we work, as opposed to before were they were more interested in the more superficial side of the business and how our products were looking.

Nevertheless I think the a balance between the two needs to be established, and platforms were research is shared are definitely important. For example when we did Cambio we conducted a lot of interviews, read a lot of content and we could have kept to ourselves. But then what is the purpose? So when we put together the website we wanted to say that we’ve only represented a percentage of the topic, but it is up to the audience, if they are interested, to continue to look more in depth into the topics presented in our work. It is also a responsibility we must have to current and future generations, to be much more generous.

I think that this process of sharing was truly felt in the on- going conversations happening throughout Cambio, whether through the digital material or events taking place at the Serpentine. This seems like a good point to discuss the Geo Design masters you are currently running at Eindhoven. What a time to launch a course considering the current situation we’re living in!

SF: Tell me about it!

It would be great to further discuss your experience in Geo design thus far and your ambitions for the course. Also, to ask you how you think the pandemic has effected our relationship with ecology as designers, and shifted our approach in resourcing materials?

AT: It is unlucky to start this year, but in the Netherlands we’ve been lucky to do a lot of in person teaching considering the current situation. We had a whole first semester in person and now we are starting to do that again. Our experience of teaching has put more urgency on us on speaking of these certain issues and bring reform to the way in that we teach.

SF: I would wish that more journalists would talk about Covid in relation to ecology and the climate crisis. I think most of us are aware that they are linked, but a great outcome of this situation is that it’s made the climate crisis physical and embodied. We are taking a virus around and because of it closing our environments, which has made it physical and this point is important. Sadly not enough discussion is going on about it. The conversations have been more about what you can do with a virus, and again compartmentalizing knowledge. It has not been about the ecosystem but it has been about the virus. But how can you look at the virus without looking at the ecosystem? It is clearer and clearer that entanglement is the way to look at things in terms of knowledge, development and so on. This is the most visible part of the pandemic.

In terms of design education the pandemic has made it very clear that design is an extremely humane discipline that needs physical interactions. Therefore, I think education online doesn’t work for design because it is not only about the passing of knowledge, but more about conversations, interactions, exchanging energies and having a connection to materials. I went back to teaching physically the other day at the design academy, and it was a joy to be able to do that again.

I think it has so much to do with human-scaled exchanges and the body language through which we communicate in a physical environment. As a student myself, these types of proxemic interactions are something I miss the most. I wanted to ask you on behalf of myself and many other aspiring designers at the early stages of their practice, what climate do you see us going into? and what insight or advise can you share with us to help shape our mindset for moving forward from this point?

SF: It is a difficult question. I think that it depends how you look at education. If you look at education in terms of forming professionals, I don’t necessarily believe in that. We don’t believe in professionalizing someone for a Job or a task. It is not the way we consider education, although there are other institutions that do that. I think as an advice it is important to keep the discipline closer to yourself.

AT: Don’t Compromise. For me this is extremely important because when you graduate you tend to gravitate towards whatever work comes into your hands because you need to survive. But most of the time this causes you to shift focus on the things that matter to you, and especially in the beginning you should never do that. I believe the most radical things you can do in design thinking should happen in the beginning because things get more sophisticated as you move forward.

SF: Some people think that you should be humble in the beginning and aim higher later, but it is the opposite way around. Because the more you grow the more you have necessities than in the beginning. When you graduate you have less compromises and responsibilities towards others than later on in your practice.

AT: It is really important to analyse with a clear focus the reality of design. When we started it was 2009, right after a huge economic crisis, and we knew that to us it wasn’t even important or interesting to work in big companies. Of course we enjoy collaborating with certain companies, but it is important to realize that system of design is more based on royalties and lower pay. I think that this has become more relevant now than even before. I think it is important to understand that design as a discipline is tough and not for everybody, and it is also quite important to say this as a teacher to your students. The ones that go to much more of a authorial side are maybe the one percent, and there is nothing wrong with being in the other 99 percent and working for others. It is totally fine. The problem with universities nowadays that they aims to fulfil this idea that everyone can be an author.

I wanted to conclude by asking you about what you’re looking forward to in the near future? And what direction do you see your practice moving towards from this point?

SF: Let’s start from what is very close by. Cambio will travel, and its expanding in the way it was mentioned before by Andrea. It is travelling to Tuscany and it will expand there, and then to Switzerland and it will expand there as well into a new section, were we will do a extended third version of the catalogue. We are hoping for it to also make it to Mexico, but with the current situation that is a bit more uncertain and difficult to plan. But there is a touring of the exhibition. In terms of our practice in a much longer term, lets say the next ten years, we wish to continue working in the way we currently are, but possibly making the research projects more radical, and the commercial projects more commercial so we can make the radical projects more radical. And in the meantime find ways to input the research that we do. So not only present them and make them available to others. But also find applications for them.

Andrea and Simone I want to thank you both for your time and for joining us for this issue. It has been such an insightful conversation, and I look forward to following the development of your work and practice.

AT & SF: Welcome! it’s been a pleasure and we look forward to the issue.