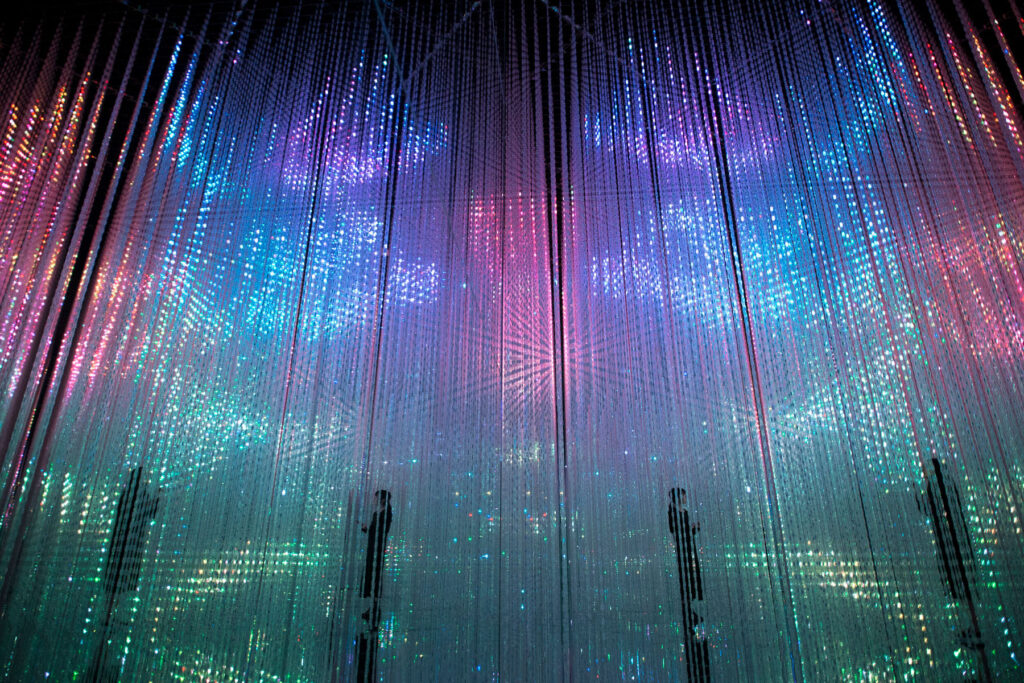

It is stated that teamLabs work fuses together art and science but can you ever really have one without the other?

A: We have always liked science and art. We want to know the world, want to know humans, and want to know what the world is for humans.

Science raises the resolution of the world. When humans want to know the world, they recognise it by separating things. In order to understand the phenomena of this world, people separate things one after another.

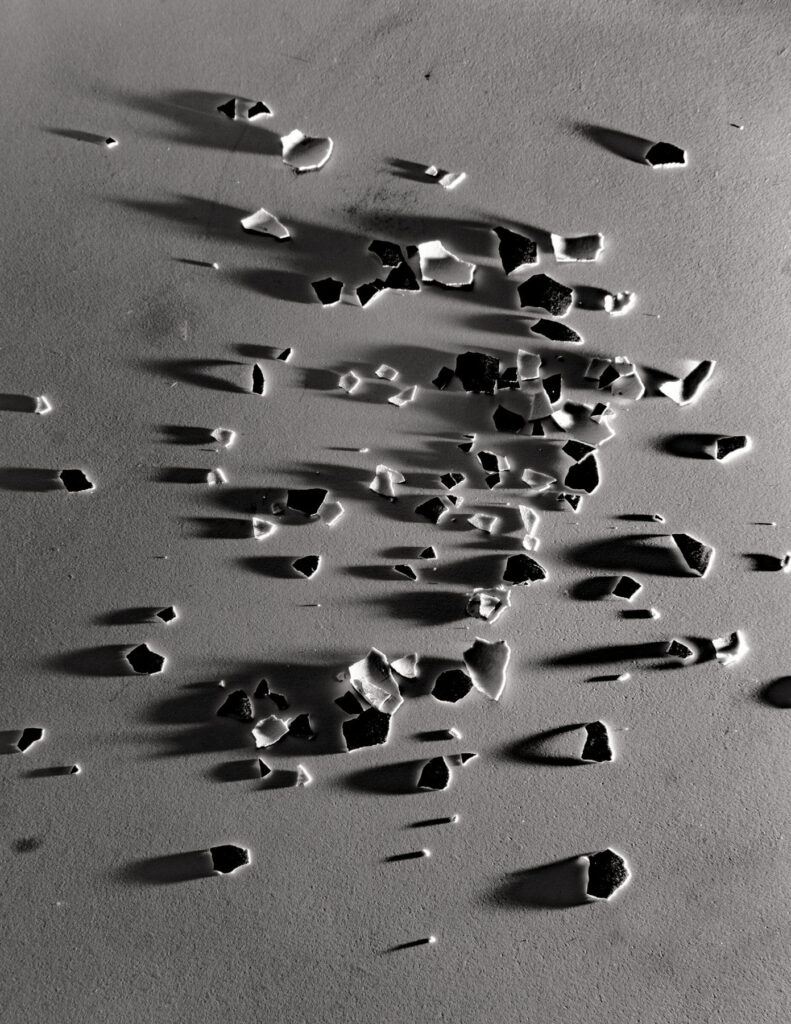

For example, the universe and the earth are continuous, however, humans recognise the earth by separating it from the universe. To understand the forest, humans break it down into trees, separating the tree from the whole. Humans then cut the tree into cells to recognise the tree, cut the cells into molecules to recognise the cells, and cut the molecules into atoms to understand the molecules, and so on. That is science, and that is how science increases the resolution of the world.

But in the end, no matter how much humans divide things into pieces, they cannot understand the entirety. Even though what people really want to know is the world, the more they separate, the farther they become from the overall perception.

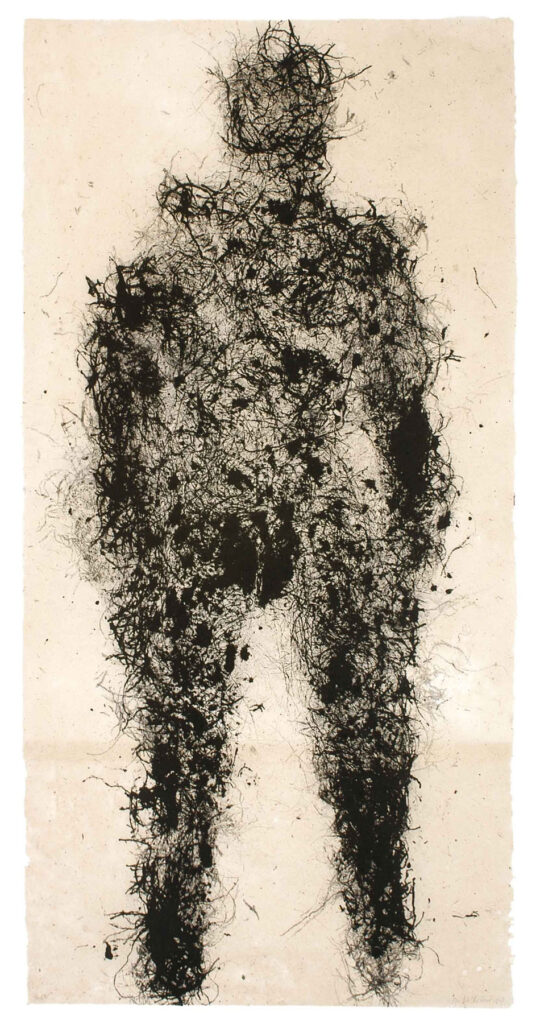

Humans, if left alone, recognise what is essentially continuous as separate and independent. Everything exists in a long, fragile yet miraculous continuity over an extremely long period of time, but human beings cannot recognise it without separating it into parts. People try to grasp the entirety by making each thing separate and independent.

Even though we are nothing but part of the world, we feel as if there is a boundary between the world and ourselves, as if we are living independently. We have always been interested in finding out why humans feel this way.

The continuity of life and death has been repeated for more than 4 billion years. However, for humans, even 100 years ago is a fictional world. I was interested in why humans have this perception.

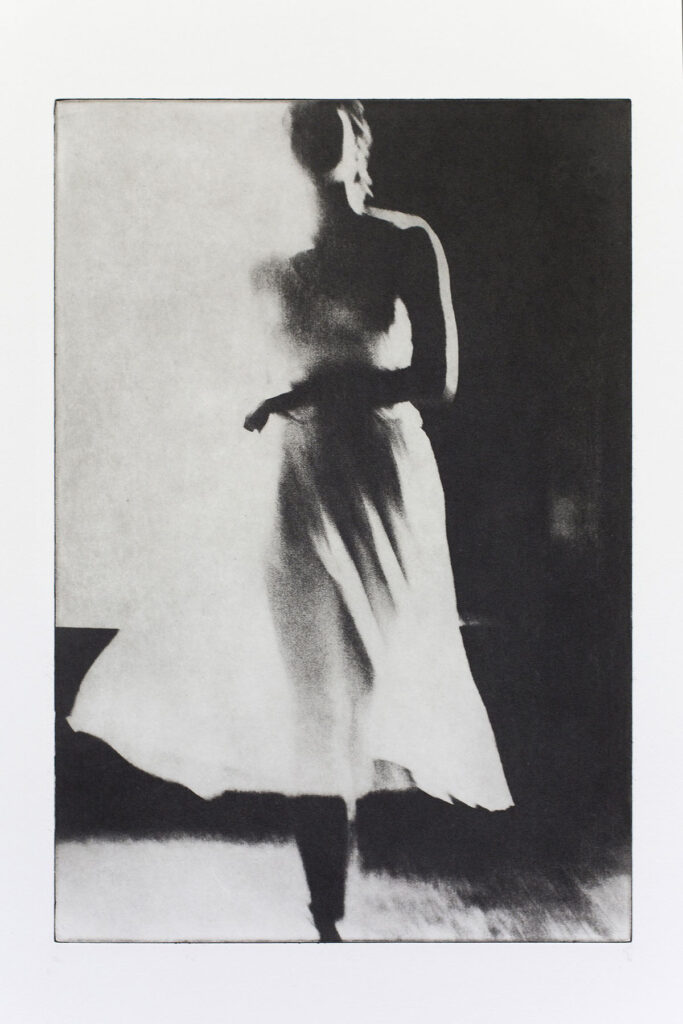

How can we go beyond the boundaries of recognition? Through art, we wanted to transcend the boundaries of our own recognition. We wanted to transcend human characteristics or tendencies in order to recognise the continuity.

Art is a search for what the world is for humans. Art expands and enhances “beauty.” Art has changed the way people perceive the world.

Groups move by logic, but individuals decide their actions by beauty. Individuals’ behaviours are determined not by rationality but by aesthetics. In other words, “beauty” is the fundamental root of human behaviour. Art expands the notion of “beauty”. Art is what expands people’s aesthetics, that is, changes people’s behaviour.

It may be the whole world or only a part of the entirety, but it is art that captures and expresses it without dividing it. Art is a process to approach the whole. And by sharing it with others, the way people perceive the world changes. Through the enjoyment of art, the notion of “beautiful” expands and spreads, which in turn changes people’s perceptions of the world.

Everything exists in a long, fragile yet miraculous continuity over an extremely long period of time. teamLab’s exhibitions aim to create an experience through which visitors recognise this continuity itself as beautiful, hence changing or increasing the way humans perceive the world.

So we can say that there is no boundary between science and art in our activity. Both of them are ways in which to recognise the world, and both are important to our aim.

Is there a specific teamLab work that stands out from the rest and if so why?

A: Our most recent works often stand out because our output is a result of accumulated knowledge and experiences.

But of our many exhibitions worldwide, one that holds a special place in our hearts is the annual outdoor exhibition teamLab: A Forest Where Gods Live in Mifuneyama Rakuen in Kyushu.

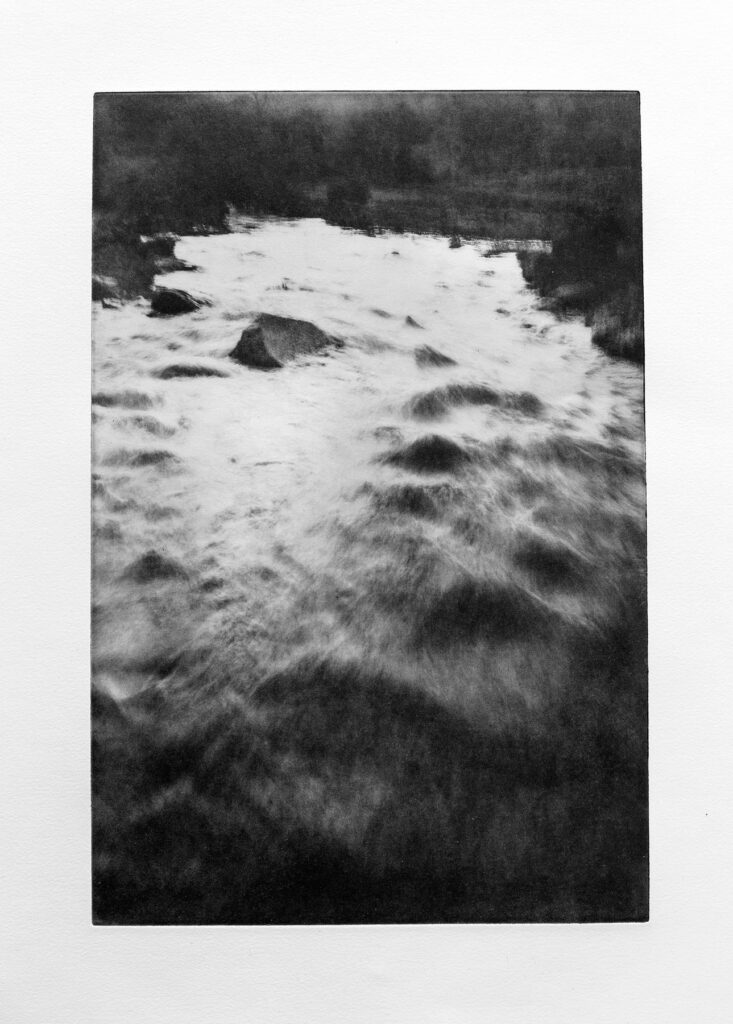

The 500,000 square meter Mifuneyama Rakuen Park was created in 1845, during the end of the Edo period. Sitting on the borderline of the park is the famous 3,000-year-old sacred Okusu tree of Takeo Shrine. Also in the heart of the garden is another 300-year-old sacred tree. Knowing the significance of this, our forebears turned a portion of this forest into a garden, utilising the trees of the natural forest. The border between the garden and the wild forest is ambiguous, and when wandering through the garden, before they know it, people will find themselves entering the woods and animal trails. Enshrined in the forest is the Inari Daimyojin deity surrounded by a collection of boulders almost supernatural in their formation. 1,300 years ago, the famous priest Gyoki came to Mifuneyama and carved 500 Arhats. Within the forest caves, there are Buddha Figures that Gyoki directly carved into the rock face that still remain today.

The forest, rocks, and caves of Mifuneyama Rakuen have formed over a long time, and people in every age have sought meaning in them over the millennia. The park that we know today sits on top of this history. It is the ongoing relationship between nature and humans that has made the border between the forest and garden ambiguous, keeping this cultural heritage beautiful and pleasing.

Lost in nature, where the boundaries between man-made gardens and forests are unclear, we are able to feel like we exist in a continuous, borderless relationship between nature and humans. It is for this reason that teamLab decided to create an exhibition in this vast, labyrinthine space so that people will become lost and immersed in the exhibition and in nature.

We exist as a part of an eternal continuity of life and death, a process that has been continuing for an overwhelmingly long time. It is hard for us, however, to sense this in our everyday lives, perhaps because humans cannot easily conceptualise time for periods longer than their own lives. There is a boundary in our understanding of the continuity of time.

When exploring the forest, the shapes of the giant rocks, caves, and the forest allow us to better perceive and understand that overwhelmingly long time over which it all was formed. These forms can transcend the boundaries of our understanding of the continuity of time.

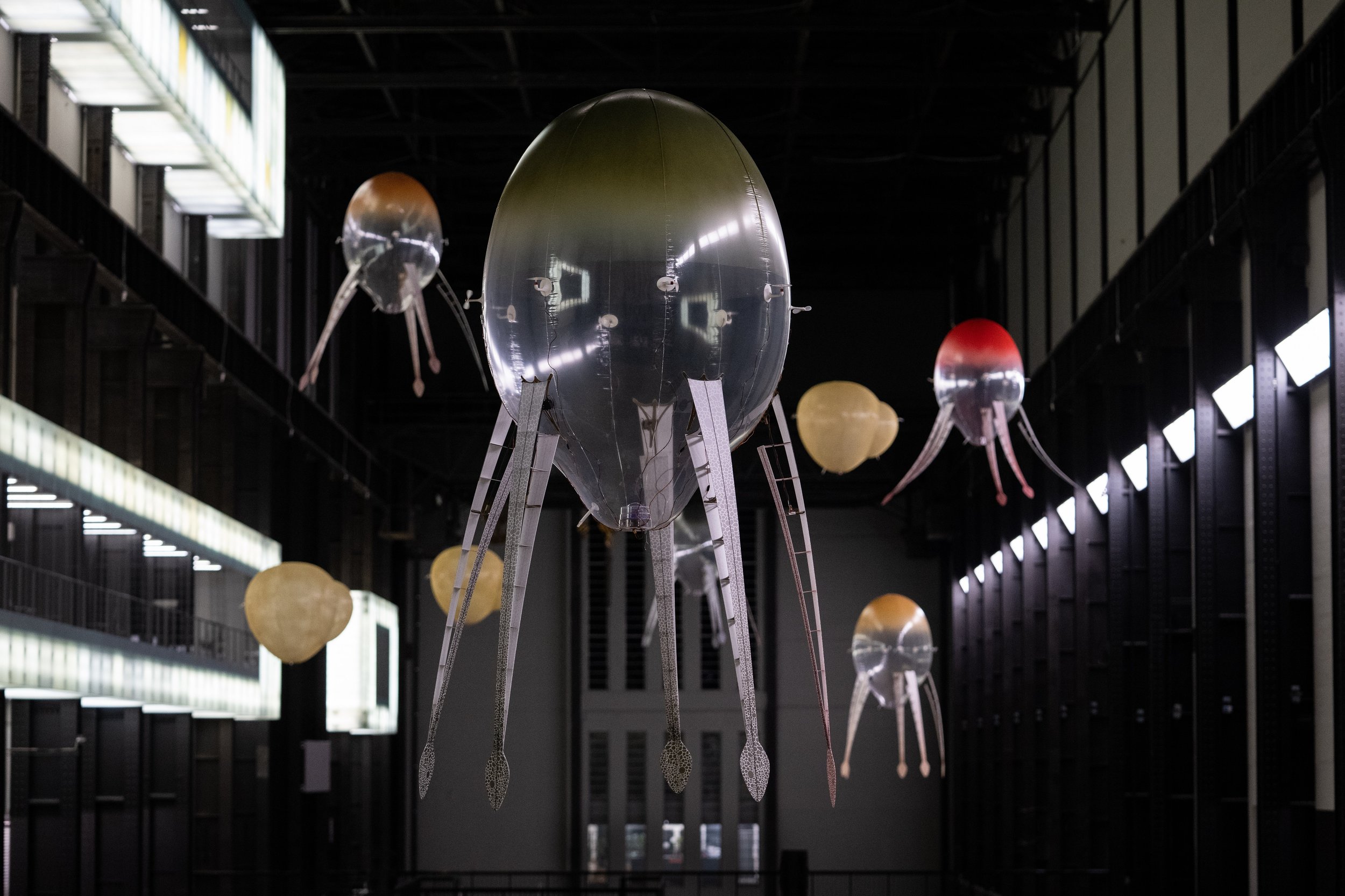

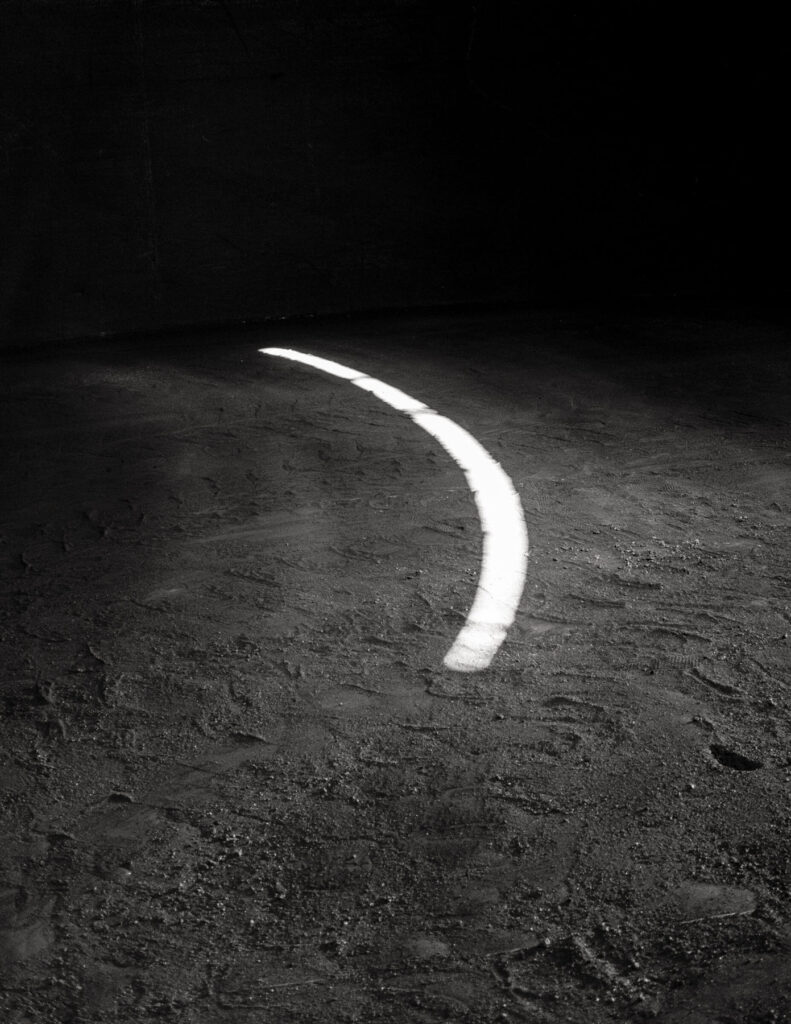

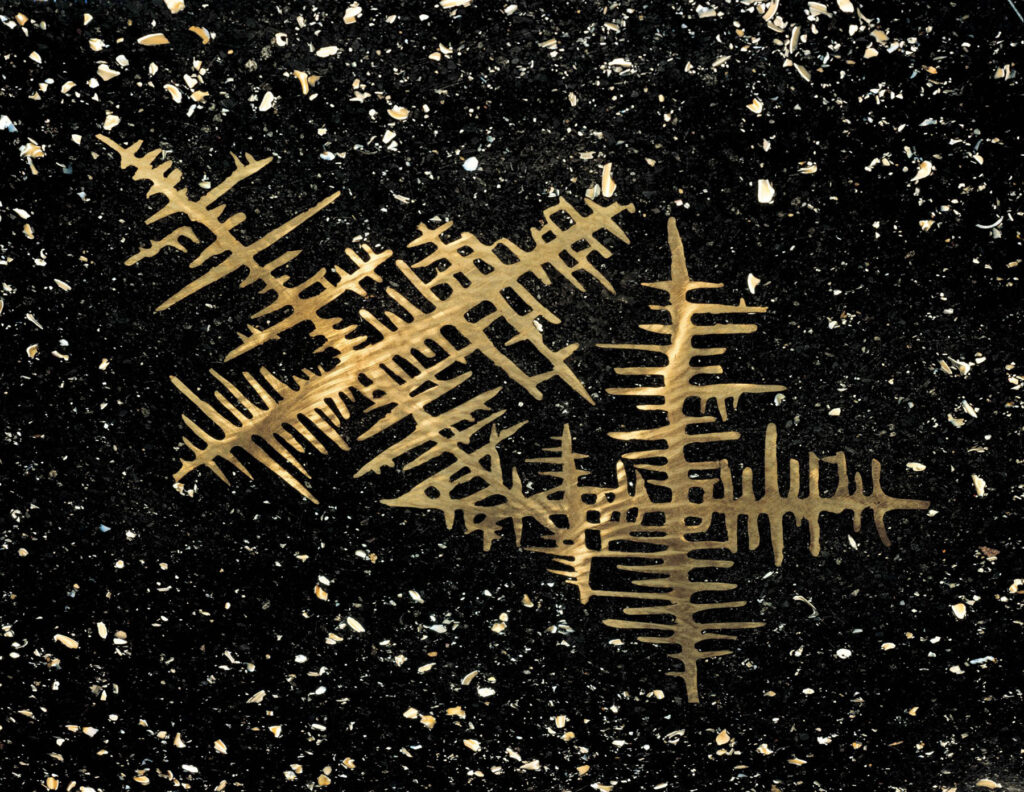

teamLab’s project, Digitized Nature, explores how nature can become art. The concept of the project is that non-material digital technology can turn nature into art without harming it.

These artworks explore how the forms of the forest and garden can be used as they are to create artworks that make it possible to create a place where we can transcend the boundary in our understanding of the continuity of time and feel the long, long continuity of life. Even in the present day, we can experiment with expressing this “Continuous Life” and continue to accumulate meaning in Mifuneyama Rakuen.

Have you found that digital interactive work has become more popular in recent years and if so why do you think that is the case?

A: To be honest, we do not know.

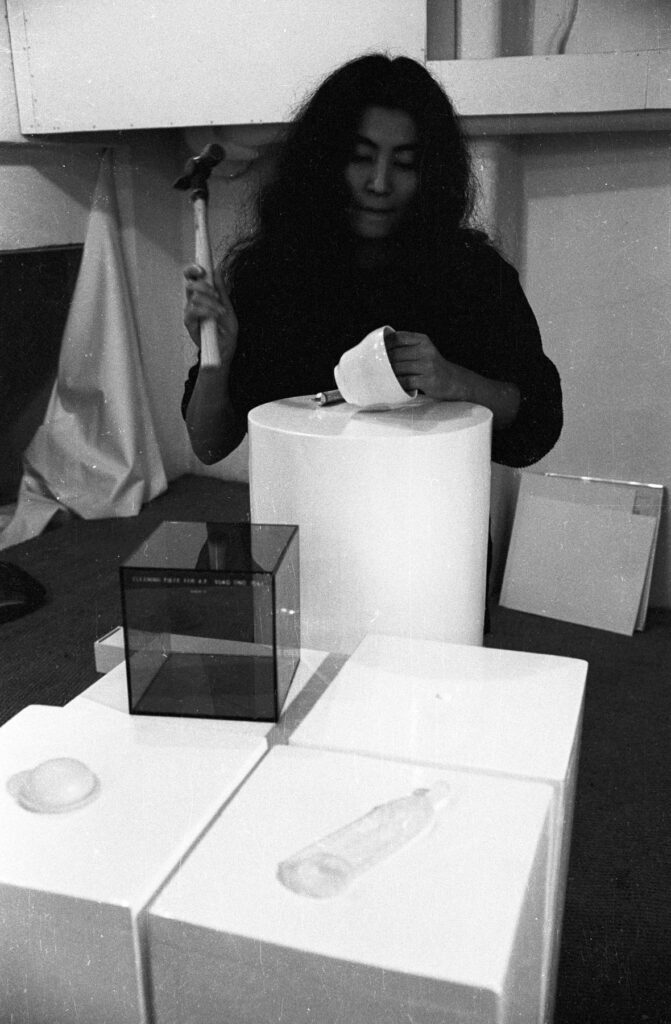

All we can say is that teamLab believes digital technology can expand art and that art made in this way can create new relationships between people.

Digital technology enables complex detail and freedom for change. Before people started accepting digital technology, information and artistic expression had to be presented in some physical form. Creative expression has existed through static media for most of human history, often using physical objects such as canvas and paint. The advent of digital technology allows human expression to become free from these physical constraints, enabling it to exist independently and evolve freely.

No longer limited to physical media, digital technology has made it possible for artworks to expand physically. Since art created using digital technology can easily expand, it provides us with a greater degree of autonomy within the space. We are now able to manipulate and use much larger spaces, and viewers are able to experience the artwork more directly.

The characteristics of digital technology allow artworks to express the capacity for change much more freely. Viewers, in interaction with their environment, can instigate perpetual change in an artwork. Through an interactive relationship between the viewers and the artwork, viewers become an intrinsic part of that artwork.

In interactive artworks that teamLab creates, because viewers’ movement or even their presence transforms the artwork, the boundaries between the work and viewers become ambiguous. Viewers become a part of the work. This changes the relationship between an artwork and an individual into a relationship between an artwork and a group of individuals. A viewer who was present 5 minutes ago, or how the person next to you is behaving now, suddenly becomes important. Unlike a viewer who stands in front of a conventional painting, a viewer immersed in an interactive artwork becomes more aware of other people’s presence.

Unlike a physical painting on a canvas, the non-material digital technology can liberate art from the physical. Furthermore, because of its ability to transform itself freely, it can transcend boundaries. By using such digital technology, we believe art can expand the beautiful. And by making interactive art, you and others’ presence becomes an element to transform an artwork, hence creating a new relationship between people within the same space. By applying such art to the unique environment, we wanted to create a space where you can feel that you are connected with other people in the world.

All we do is create what we believe in – our hope is that our output reaches people’s hearts and changes their ways of thinking or behaviour. Popularity is just a byproduct of that. We never consider popularity when working, all we focus on is creating something we believe in.

What advice do you have for young creatives who are interested in working with digital and interactive works?

A: teamLab was started by a group of friends who simply enjoyed spending time together, and it has continued to grow and change. If you only think in practical terms, logically, you will fail. It is good to start with the things you enjoy in life.

We aim to create artworks and experiences that allow people to experience the beauty of the world with their hearts and their bodies. In the 20th century, we were taught to only understand the world through our “heads,” but it is important to experience things with our hearts and our bodies. Do not think you can understand the world just through the internet.

Is teamLab working on anything at the moment and what plans does the collective have for the future?

A: You can find the information about upcoming exhibitions worldwide on our website – please check there for the latest updates!