“identity is subtle and evident in the design more than anything else”

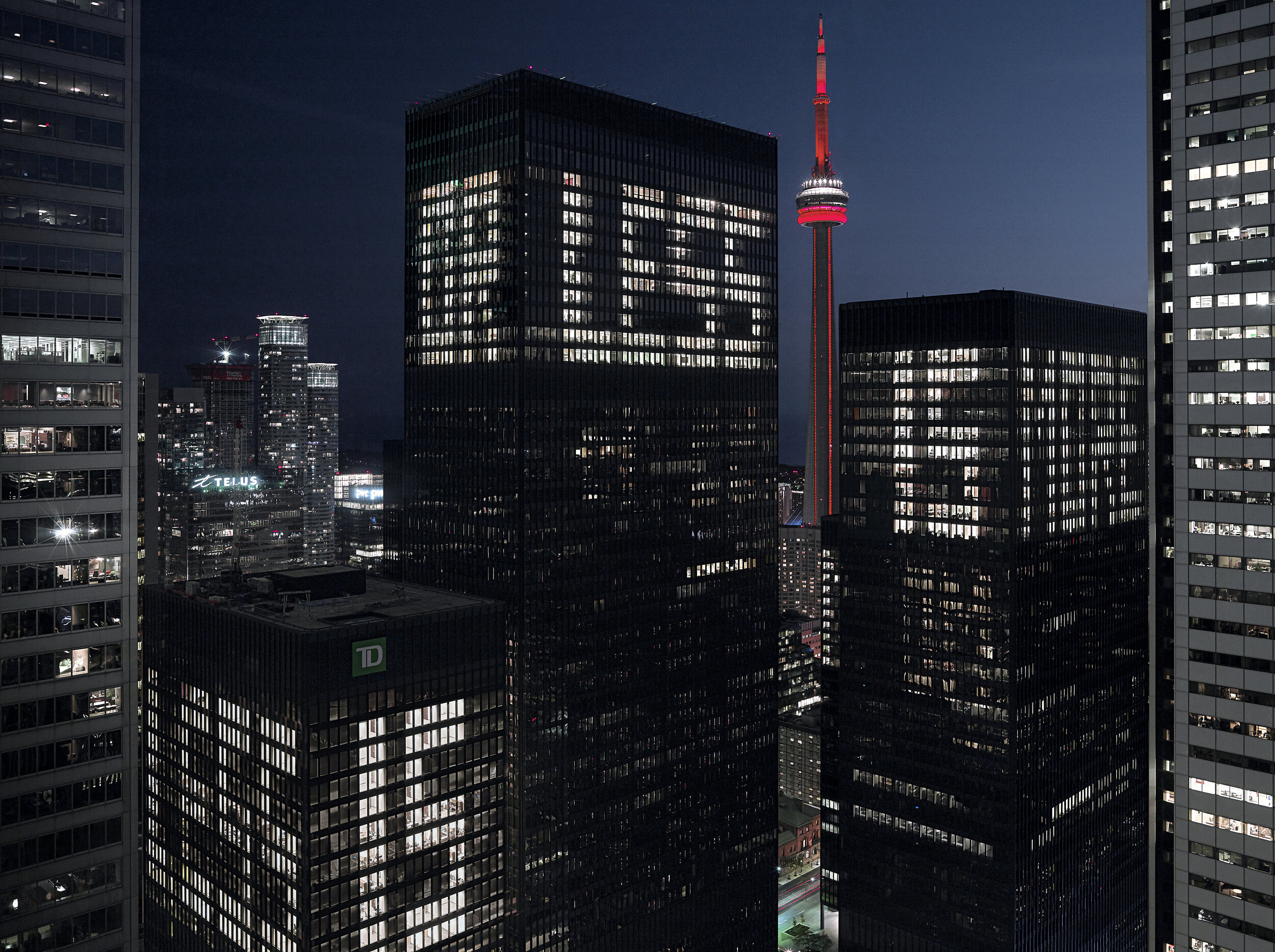

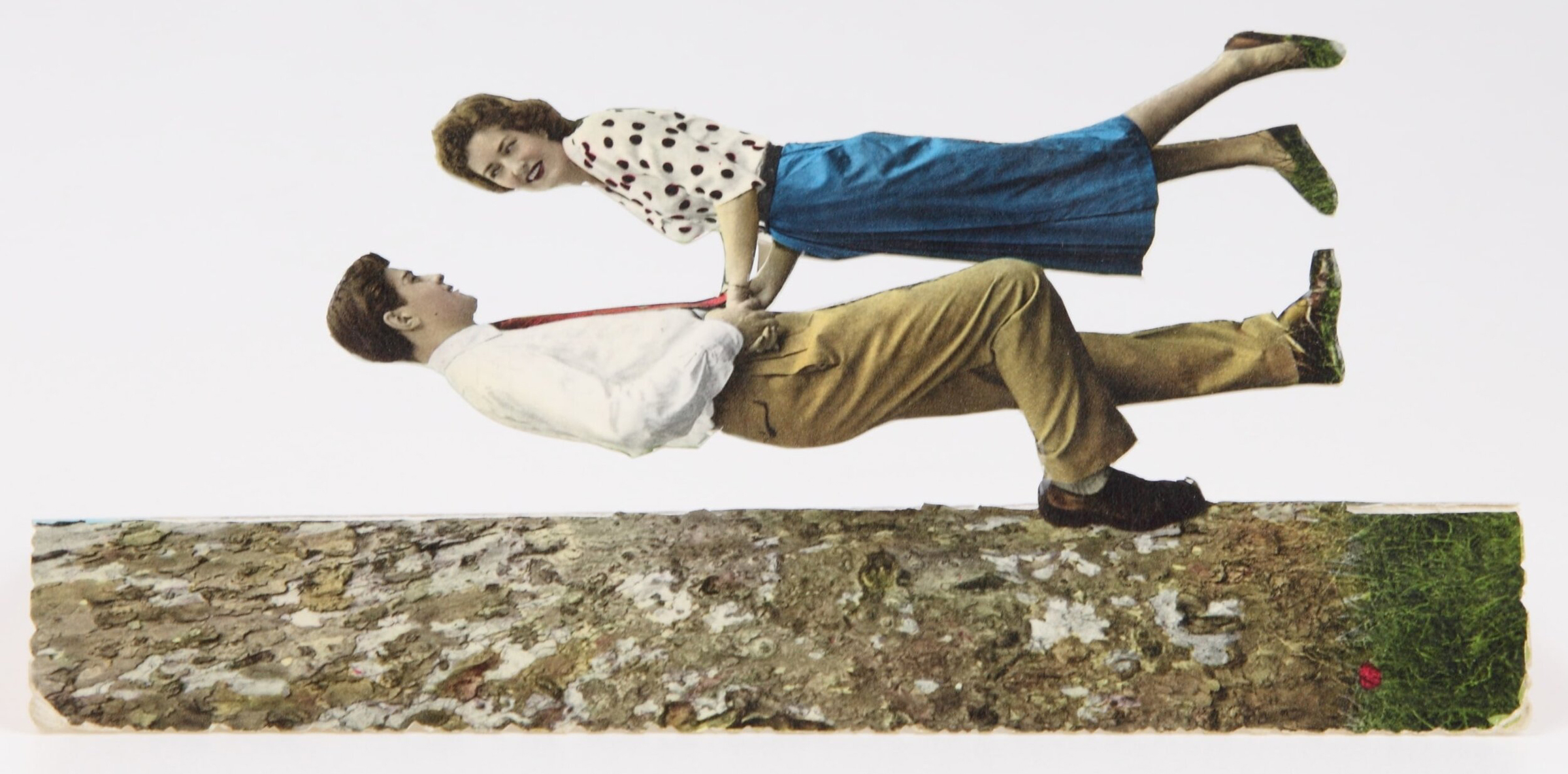

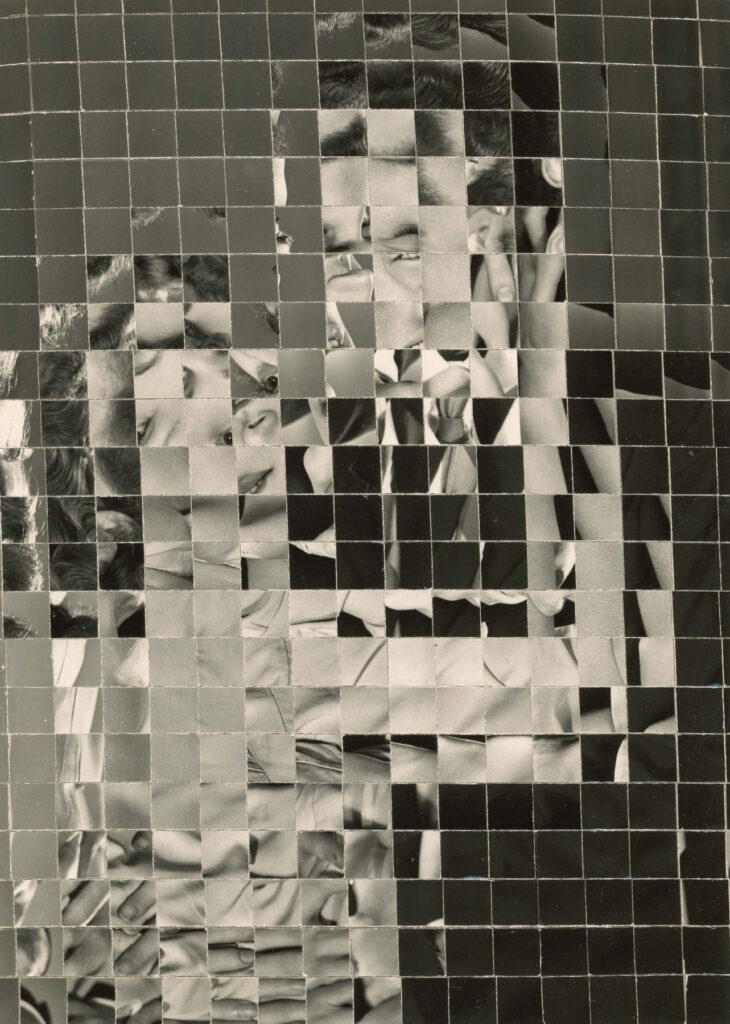

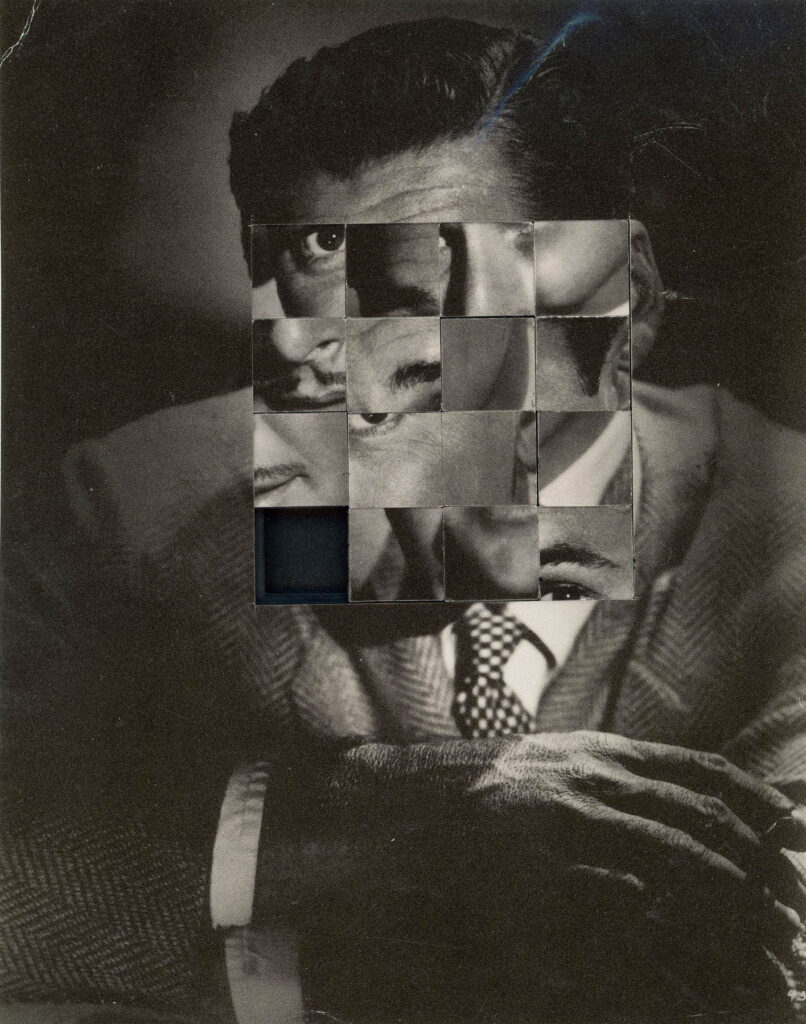

North London townhouse Canyon House has been transformed from a bedsit into a stunningly vibrant 70’s Californian-inspired home by Studio Hagen Hall, “a multidisciplinary architectural and interior design studio that focuses on crafting exceptional spaces.” The clients, Ben Garrett and Rae Morris are both recording artists and while they fell in love with the essence of the house, including the well-established garden and good location, much work was needed to enliven the place.

Originally the property had been divided into three separate bedsits with the use of awkward partitioning that split the house. The entire interior needed to be gutted and Studio Hagen Hall used digital modelling to reimagine how the space would be used allowing the clients to use a VR headset to experience the design ideas. A recording studio was also incorporated into the new design of the interior. Drawing on 70s influences the intro design is a mix of warm wood, lush mustard velvets and vibrant peaches. NR Magazine joins Louis Hagen Hall, founder of Studio Hagen Hall, in conversation.

What key elements would you say create the 70s atmosphere and design of Canyon House?

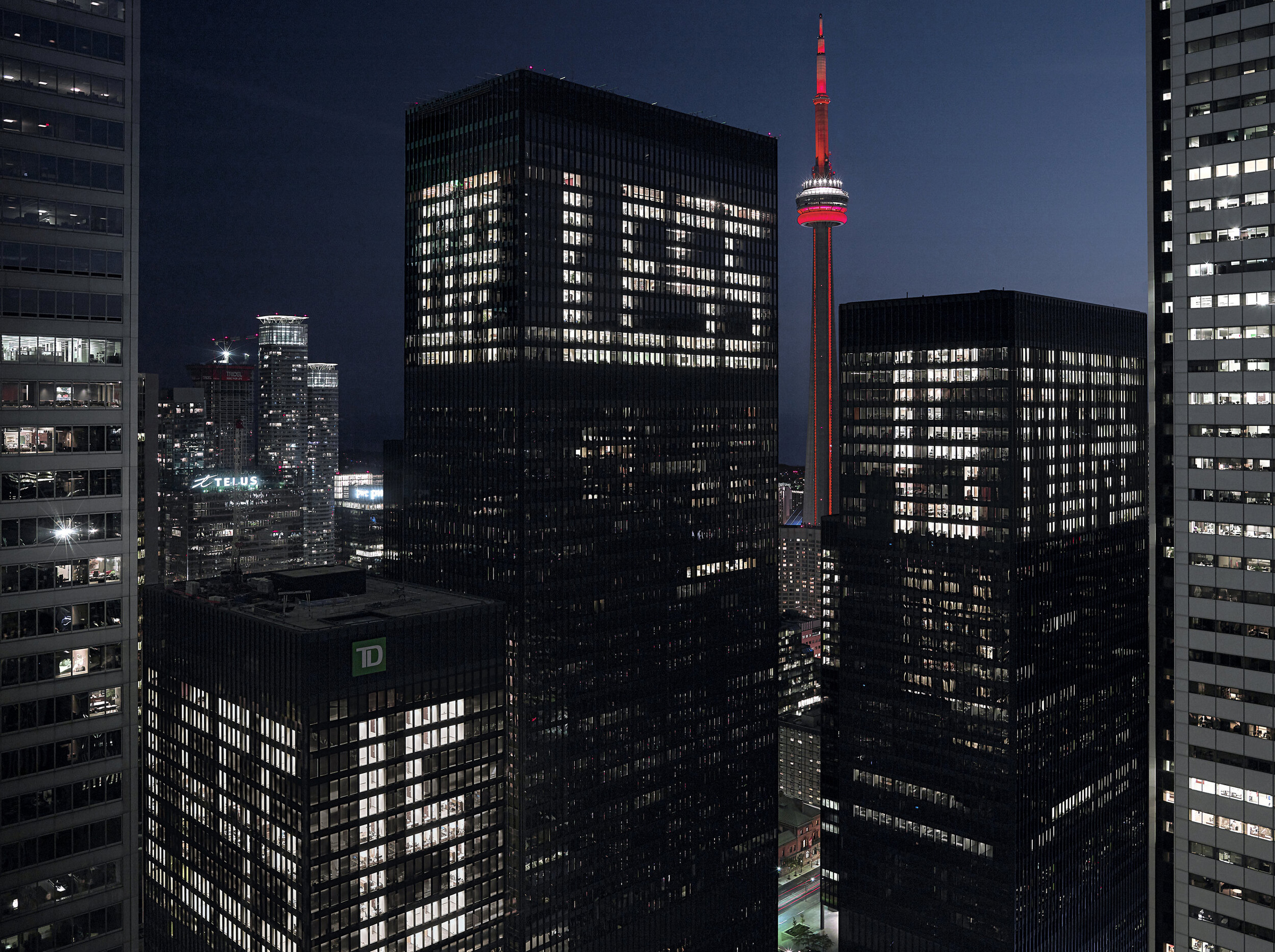

I’d say it’s the combination of design features and materiality. We made a conscious decision to try and evoke a 70s atmosphere by means of reinterpretation rather than creating a pastiche of that era. To that end, there are nods to popular features of that era (such as the “conversation pit”, the “kitchen/dining serving hatch” and “open stair”), which we adapted to suit the house. Materially, we used typical materials from that period, such as Elm, velvet, and fluted glass, and chose colours with a particular 70s feel to them. Even the live/work form of the house pays homage to Ray & Charles Eames (the clients are musicians who collaborate and work together).

Are there any new technologies in architecture and design that you are particularly excited about?

We’re particularly interested in new materials – both re-cycled (for example “Smile Plastics”) and organic (particularly mycelium & hemp, which are starting to become more prevalent in the construction industry).

The re-emergence of old technologies as “new technologies” is also fascinating – such as the use of clay and lime renders and natural insulation (eg paper & wool).

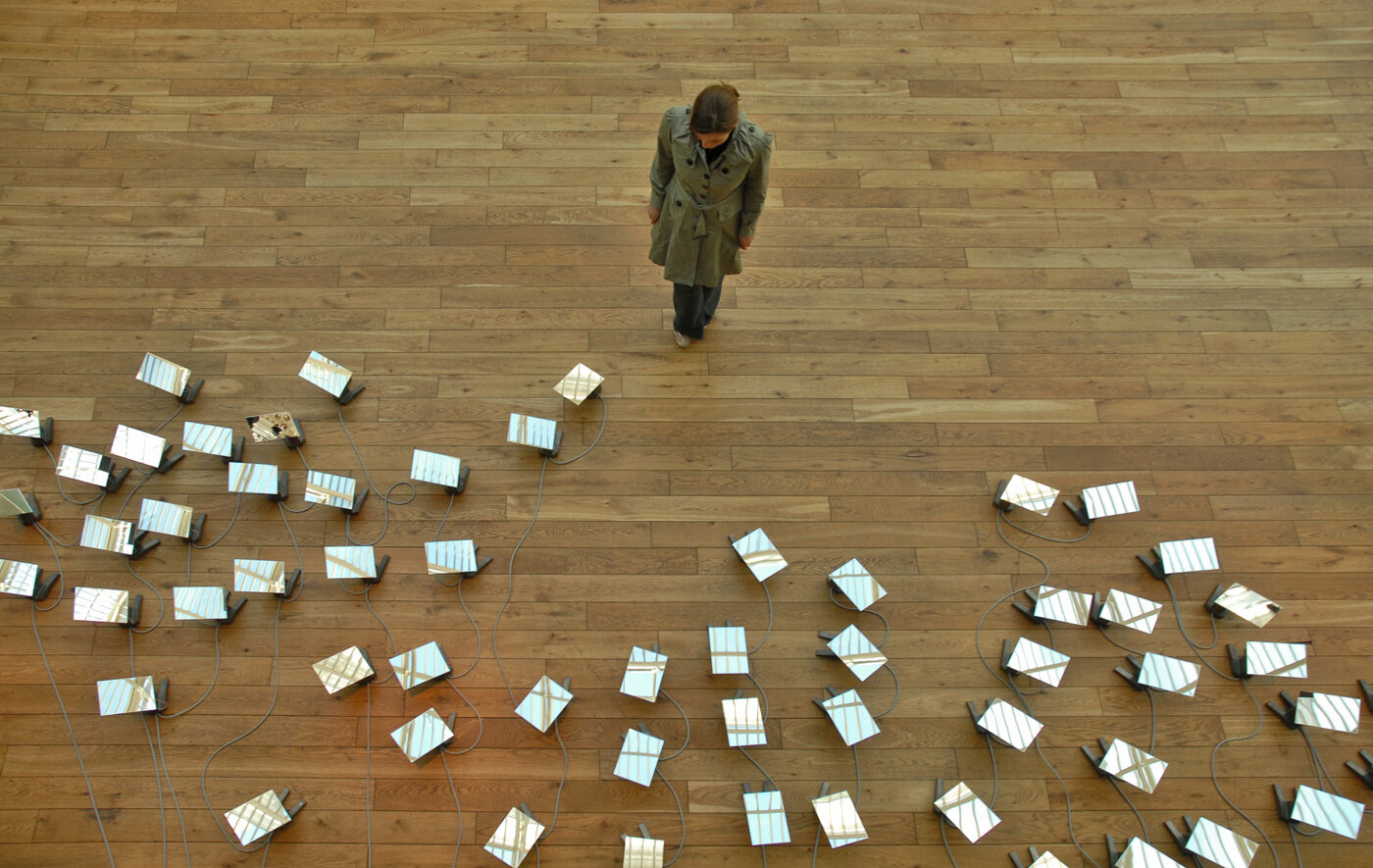

From a design-process point of view – easier and cheaper access to Virtual Reality has made it a very powerful tool. We can now walk clients through a space to better explain it, and even test out designs ourselves and leave annotations in the model in real-time.

What was the most challenging aspect of this project?

Boiling it down to one sentence – the biggest challenge was trying to make what is essentially a relatively small British terraced property feel like a large free-standing Californian canyon house!

Ultimately we achieved this by spending a lot of time working out how to best reconfigure the house as a whole. We spent a great deal of time working on creating a natural flow throughout the spaces (both visual and circulatory), while also improving the relationship between the interiors and exterior spaces. When it came to the decor itself, we were all very much on the same page – so once we had cracked the layout of the house, the rest came relatively easily.

You stated that people who spend time at Canyon House don’t want to leave, why do you think that is?

It’s a particularly comfortable, relaxing and sociable space to spend time in, and there are often people coming and going either for work (musicians coming to work with the client in the studio) or friends and family dropping by for a cup of tea. I think it also has something to do with how the light is always changing. Just when you feel like it’s time to leave, the sunlight will shift onto a different surface, changing the mood, or evening will fall and the lights will come on, completely transforming the house again.

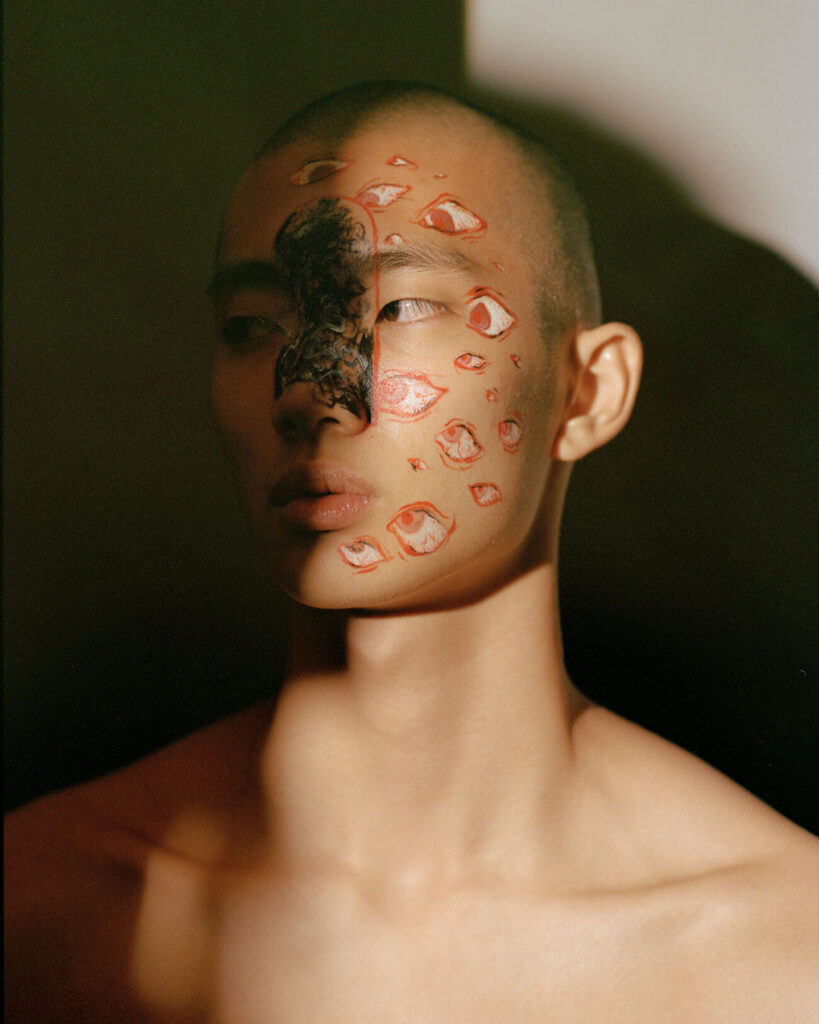

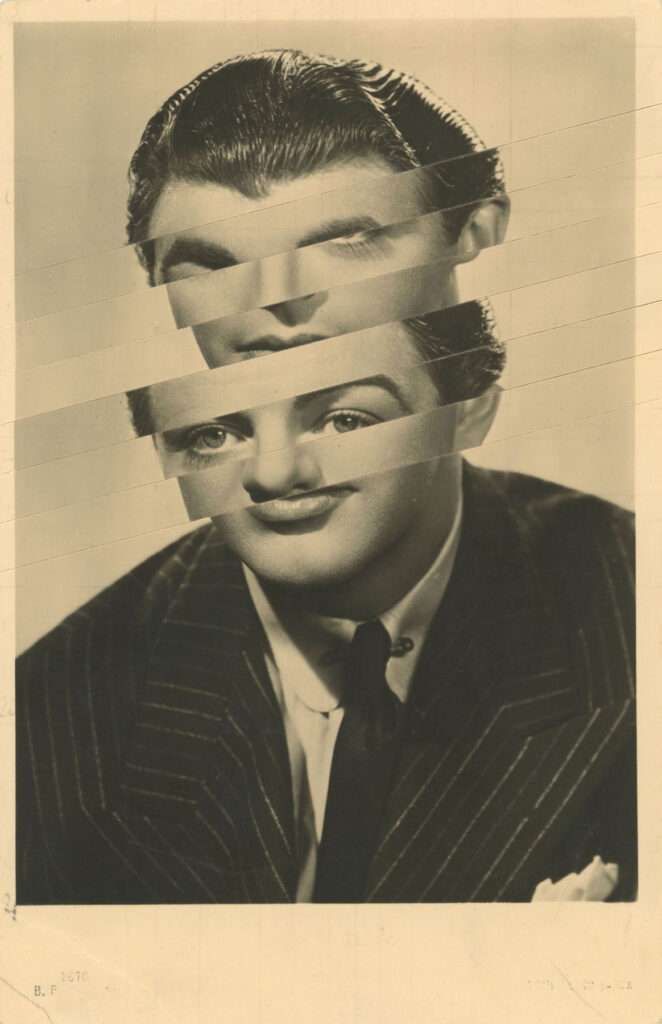

What does identity mean to you as an architect?

Obviously, there is a visual identity – which can be hard to maintain across a wide range of projects and clients – although we try to maintain some consistency through the use of details and materials (which in turn relates to our stance on sustainability).

But I think there is a practical identity as well – creating usable, functional spaces, which isn’t always obvious through images. I will often try and show new clients around past projects (luckily I have very supportive clients) to experience this for themselves.

There is also identity in methodology and process, which I think can be apparent through displaying work in progress, drawings, models, etc.

“For us, identity is subtle and evident in the design more than anything else, rather than a case of branding or deliberate market positioning.”

Canyon house was originally separated by awkward partitions into self-contained bedsits and the house had to be stripped back to its shell. Do you think this is a common issue in London and if so does it affect the quality of living?

It is a common issue in London, especially as people try to exploit high rental charges here. And it absolutely affects the quality of living in a negative way – houses are divided up into spaces they were not designed for, resulting in cramped conditions, and quite often bedsits will pose serious fire risks (often due to kitchens being squeezed into bedrooms and hallways).

The ONE positive thing you could say about bedsits is that they do (in an unintentional, ad hoc way) form a sort of cohabitation/communal living typology – something that is being explored more and more these days. But this needs to be designed deliberately to be successful.

How does sustainability fit into your work with Canyon House?

We try to adhere to two main sustainability principles:

1. The principle of ‘embodied energy’ (which is the energy consumed to manufacture, transport, and assemble building materials to construct a building) – so we try to use as few processed materials as possible (eg clay render onto plywood rather than plaster onto plasterboard), as many renewable materials as possible (eg timber – always FSC certified – instead of steel and concrete), and we try to have any off-site items (joinery, fittings etc) produced as locally as possible to cut down on transport and shipping. We are also trying to integrate more and more natural and recycled materials into our projects, which cuts down on overall energy and resource consumption.

2. Re-use or ‘retrofit’ rather than demolish + re-build – renovating an existing building is almost always more environmentally beneficial than demolishing an existing structure and building a more energy-efficient one. So we try to encourage re-use by upgrading and extending structures rather than demolishing and building anew. And where this is not possible, we encourage our clients to work with as much of the existing building fabric as possible. For example, we are working on a new-build house in Dungeness, and while we are having to remove the existing building (because it is completely unsalvageable), we are designing the new building to match the footprint of the existing foundations, which is far more sustainable (and also cost-saving).

How has the pandemic affected your work practice?

On the practical side of things, we had to give up our studio as it was part of a large co-working space and it was closed for long periods of time. We eventually got into the swing of working from home, which has had the long term benefit of making everyone (including clients) more comfortable with communicating via video call. This can be very beneficial to a small design practice as it can be hugely time (and therefore cost) saving.

In terms of surviving during the downturn in work – we lost a few new commercial jobs, but we used the downtime to re-brand, re-build websites and social networks, and even launch a new kitchen/joinery practice called “b y s s e” with our long time collaborator and friend, joiner Tim Gaudin.

When things began to open up again, we started working in a smaller co-working space called Benk & Bo (in East London) a few days a week, and now we are working together with them on their new venues! So where some doors closed, others have opened.

Do you have any advice for young creatives looking to work in architecture and design?

I can only speak from experience – but knowing what I know now, I would say don’t rush anything! Take your time to find your creative space and let things happen to you, or you might find yourself going in a direction you didn’t want to. When there are natural breaks (particularly in the case of the time between Undergrad and Masters Degrees for architecture students) take the time to work in, or with, other fields. Volunteer for charities and meet people from all different aspects of life. Travel if you can. Teach if you can. Oh, and make friends with people outside of your field of interest!

I never used to be one for networking, but it turns out interesting things can come out of it. This doesn’t have to mean typical “networking events” – I have met like-minded collaborators at all kinds of different talks and evenings (even things like wine tasting!) Good Architecture and Design comes from experience – not just practical, but cultural.

Also, I feel quite strongly that a lot of students and young creatives feel pressured into qualifying or breaking onto a scene as soon as possible, partly because it takes a long time to qualify and/or become established, but also because we tend to glorify “young achievers” with awards for “best young designer” and publications like the “40 under 40”. Age is irrelevant – take your time, find your own space, and try not to compare yourself to your contemporaries!

Lastly,

“when you need help and advice, don’t be afraid or shy to ask for it. And if someone asks you, don’t hesitate to give it!”

Are you working on any projects at the moment and what plans do you have for the future?

We are just finishing off three residential refurbishments in East London, then we will be beginning a new cycle of very exciting and diverse projects…from a new-build coastal house in Dungeness, to a fashion house showroom and office, to the restoration of a mid-century masterpiece, to a Japanese inspired victorian townhouse, and a multi-purpose community-driven wood and craft workshop.

We have also just launched a kitchen & storage-specific studio & workshop together with our long-time collaborator and friend, Tim Gaudin – called “b y s s e” (www.bysse.co)

And we’re finally planning on adding to our team of architects and designers after a long wait, which is hugely exciting! Ultimately we would like to open a second studio in Europe.

Credits

Images · STUDIO HAGEN HALL

https://www.studiohagenhall.com/