“the creation of new perspectives can be found in the old, the ordinary and the familiar”

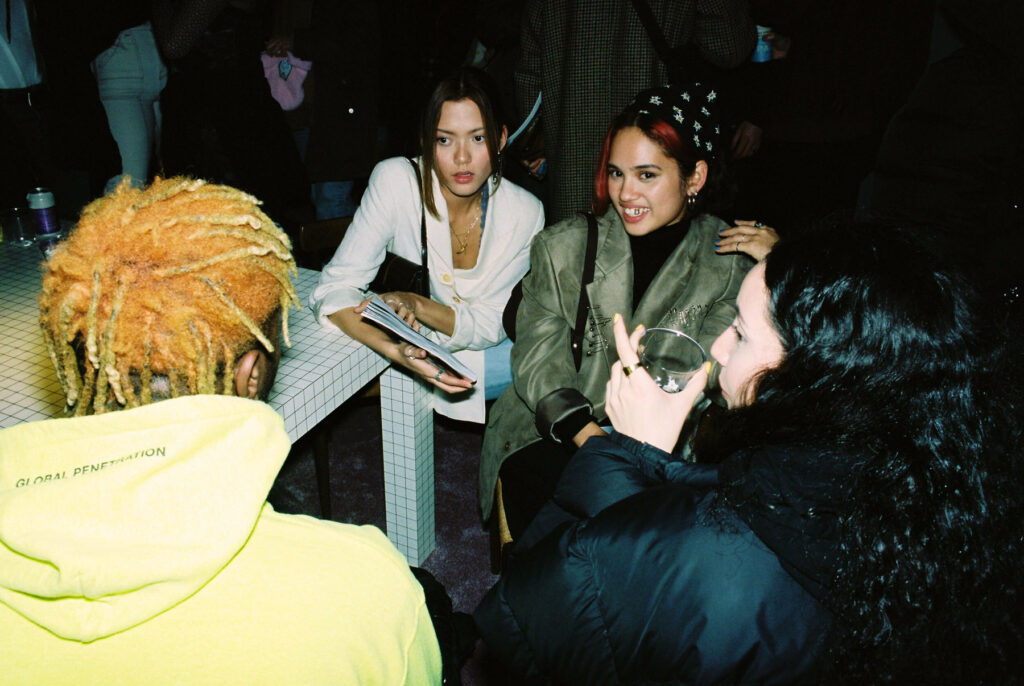

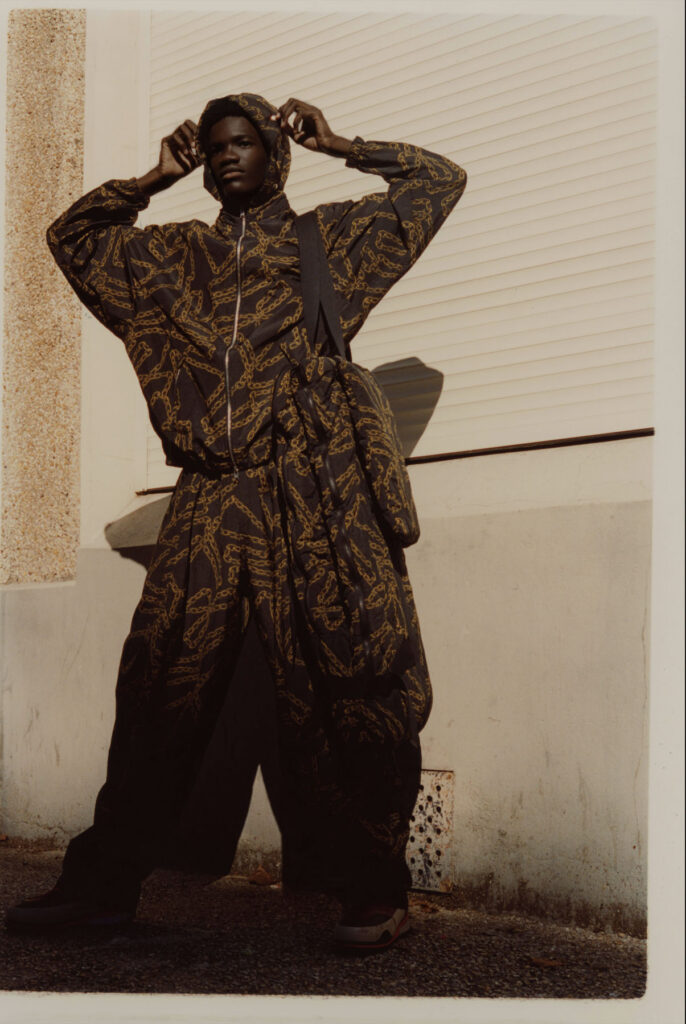

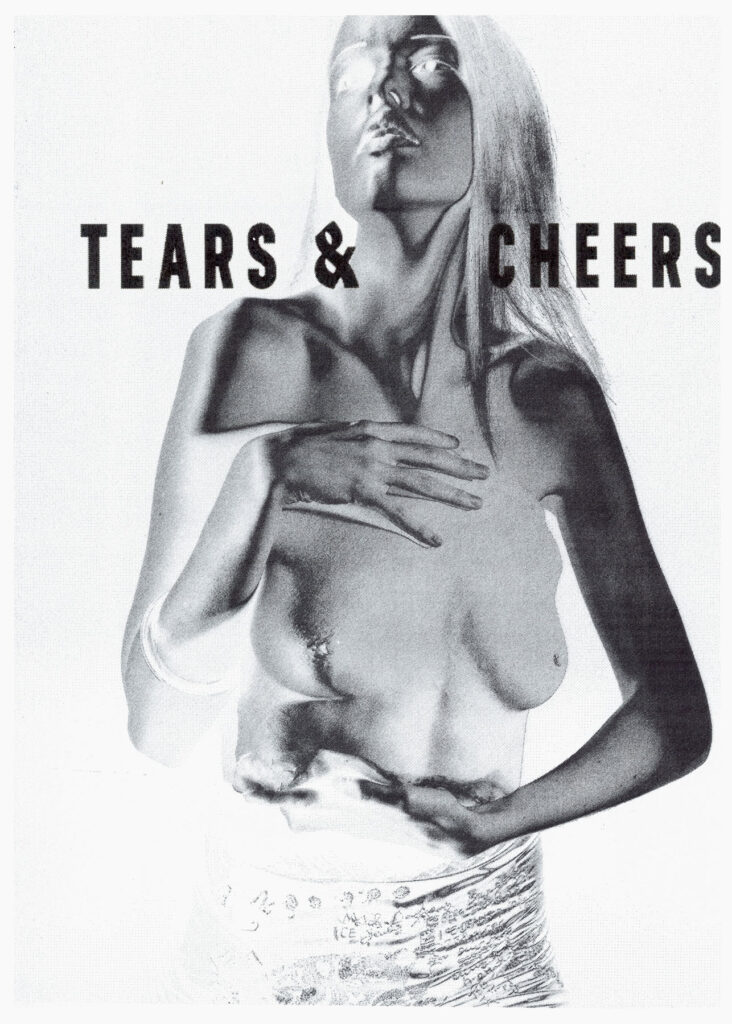

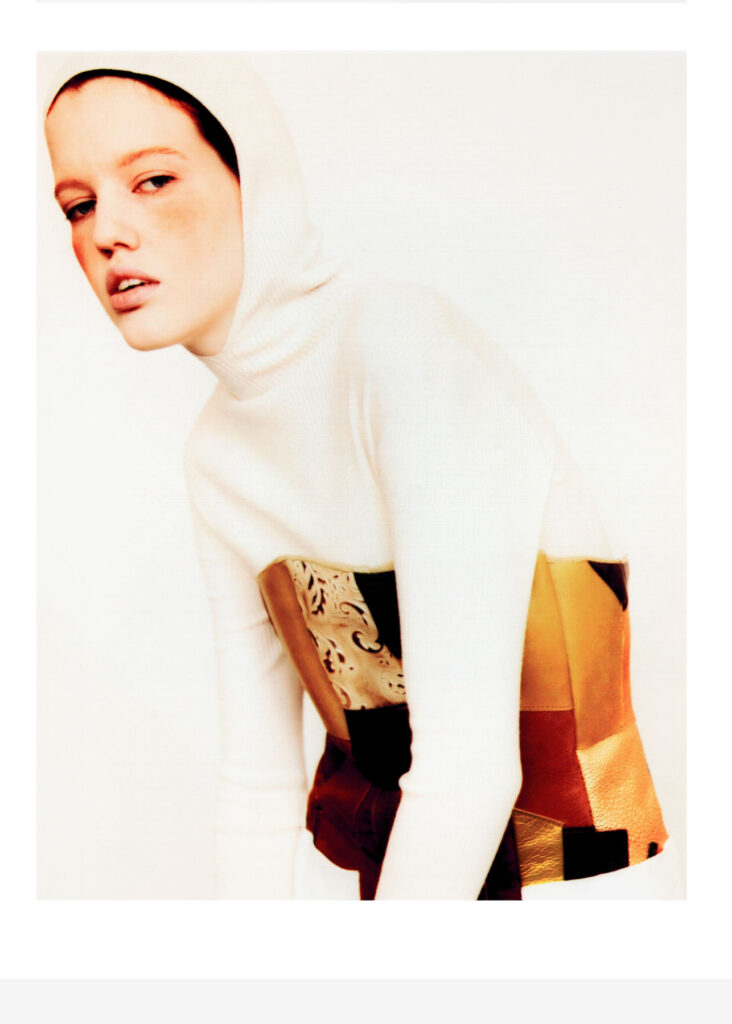

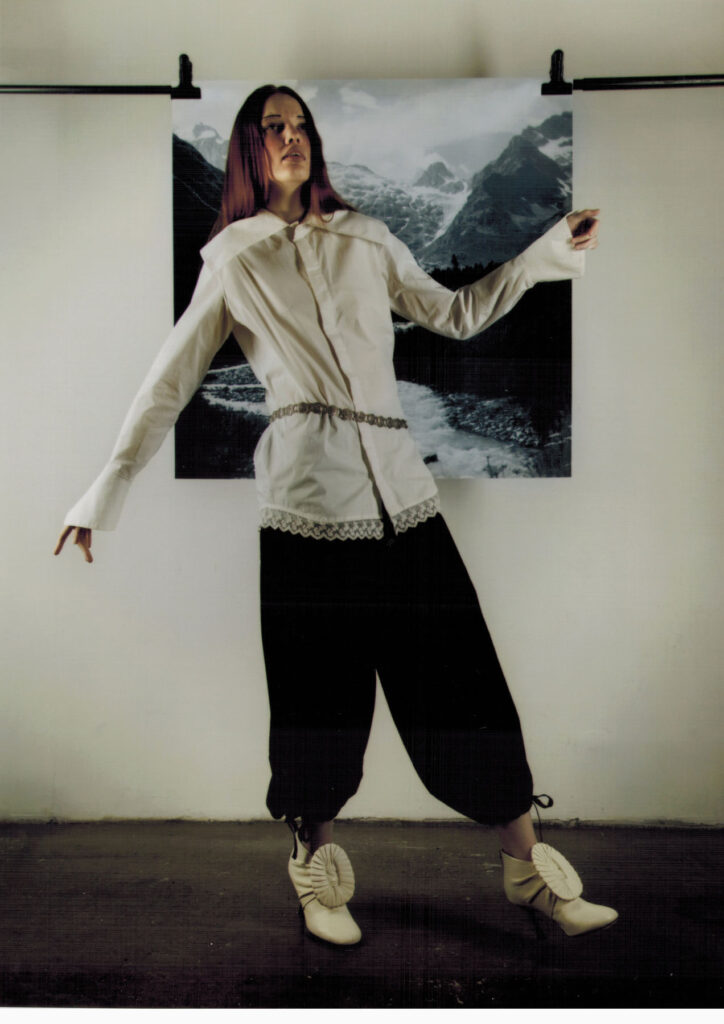

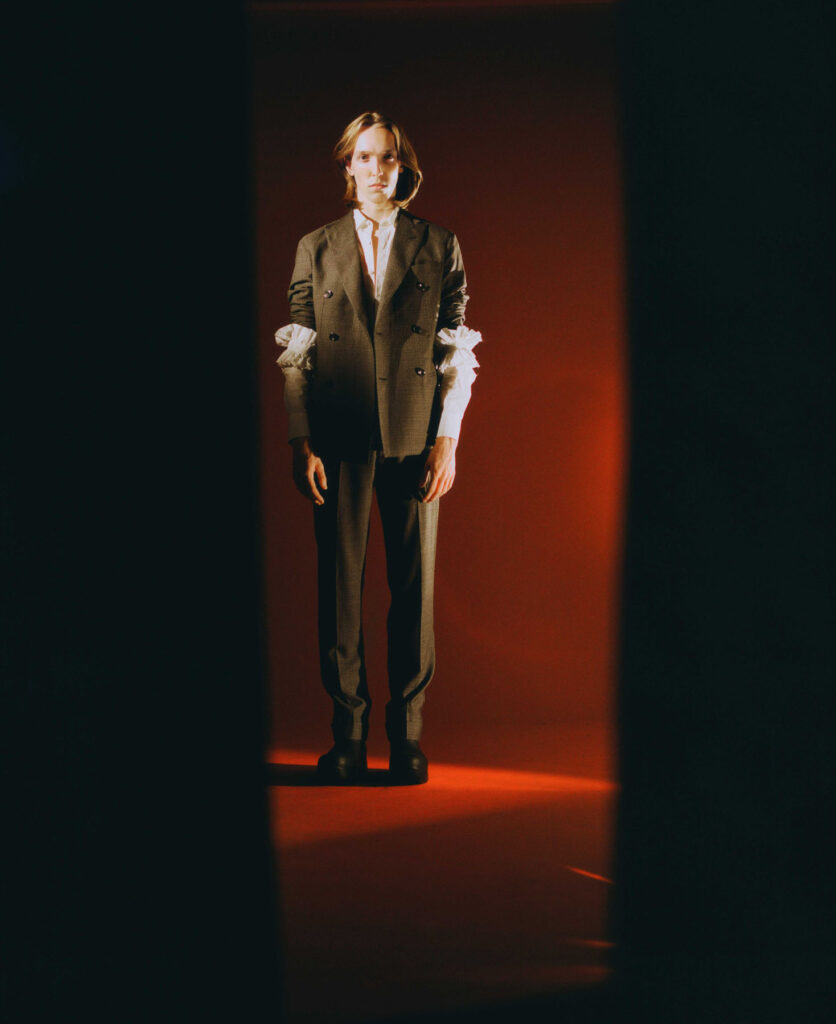

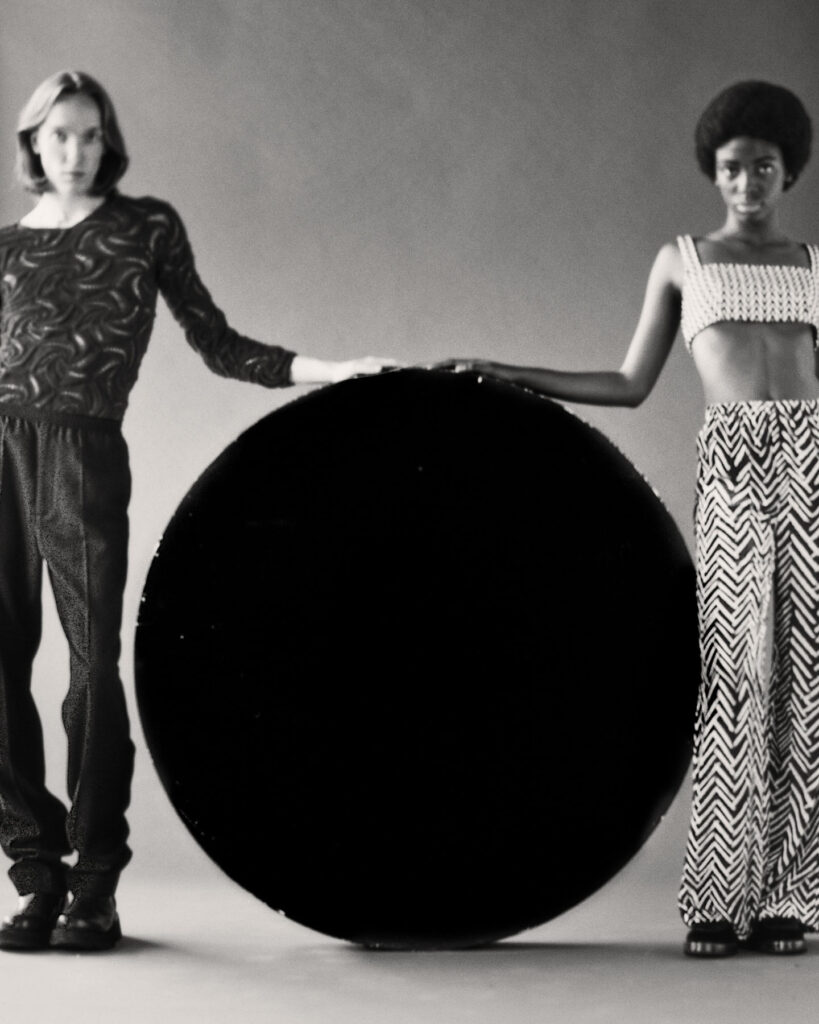

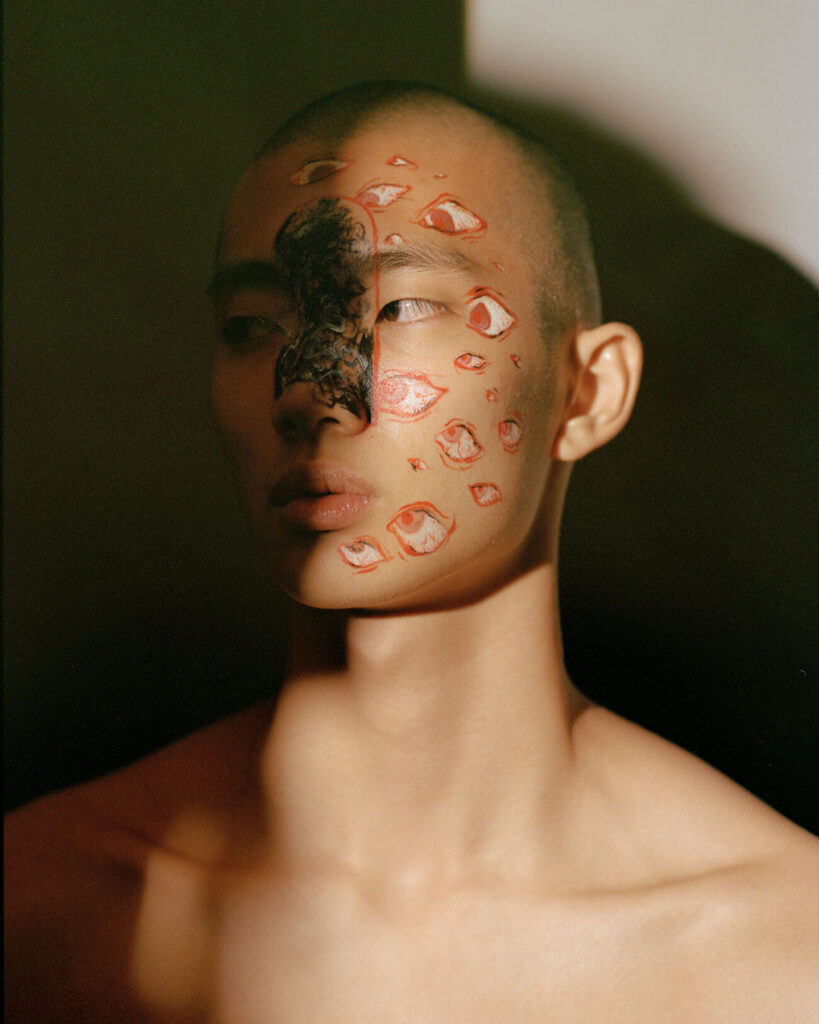

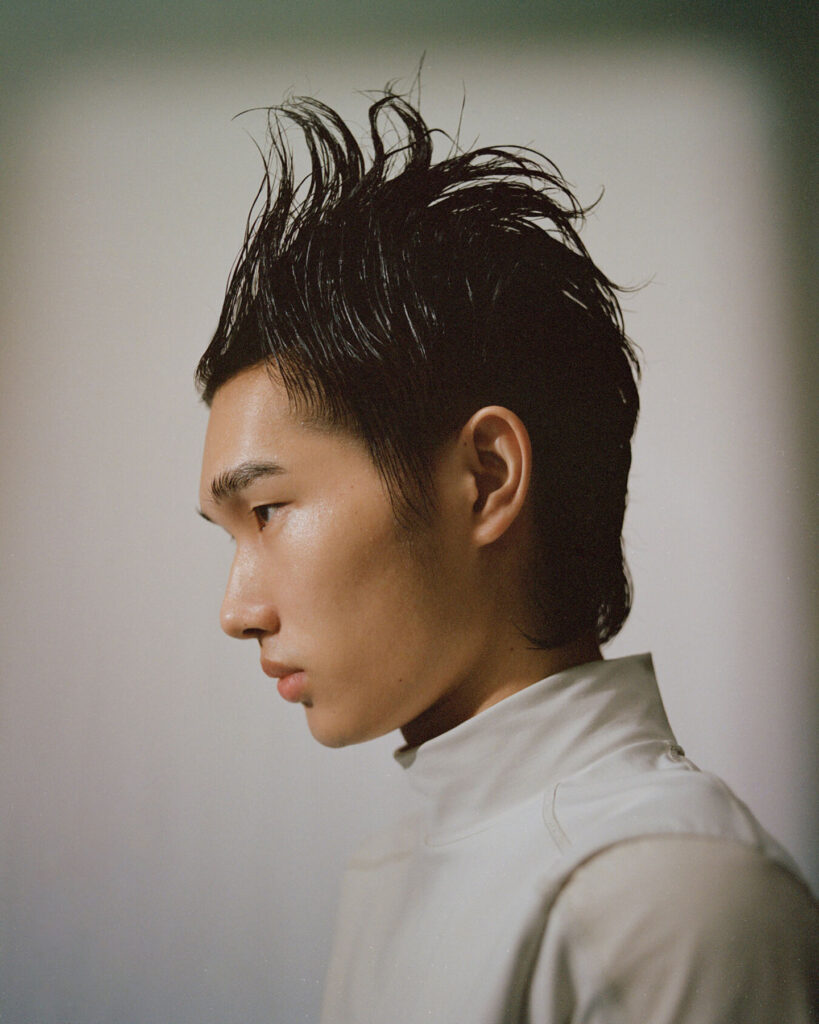

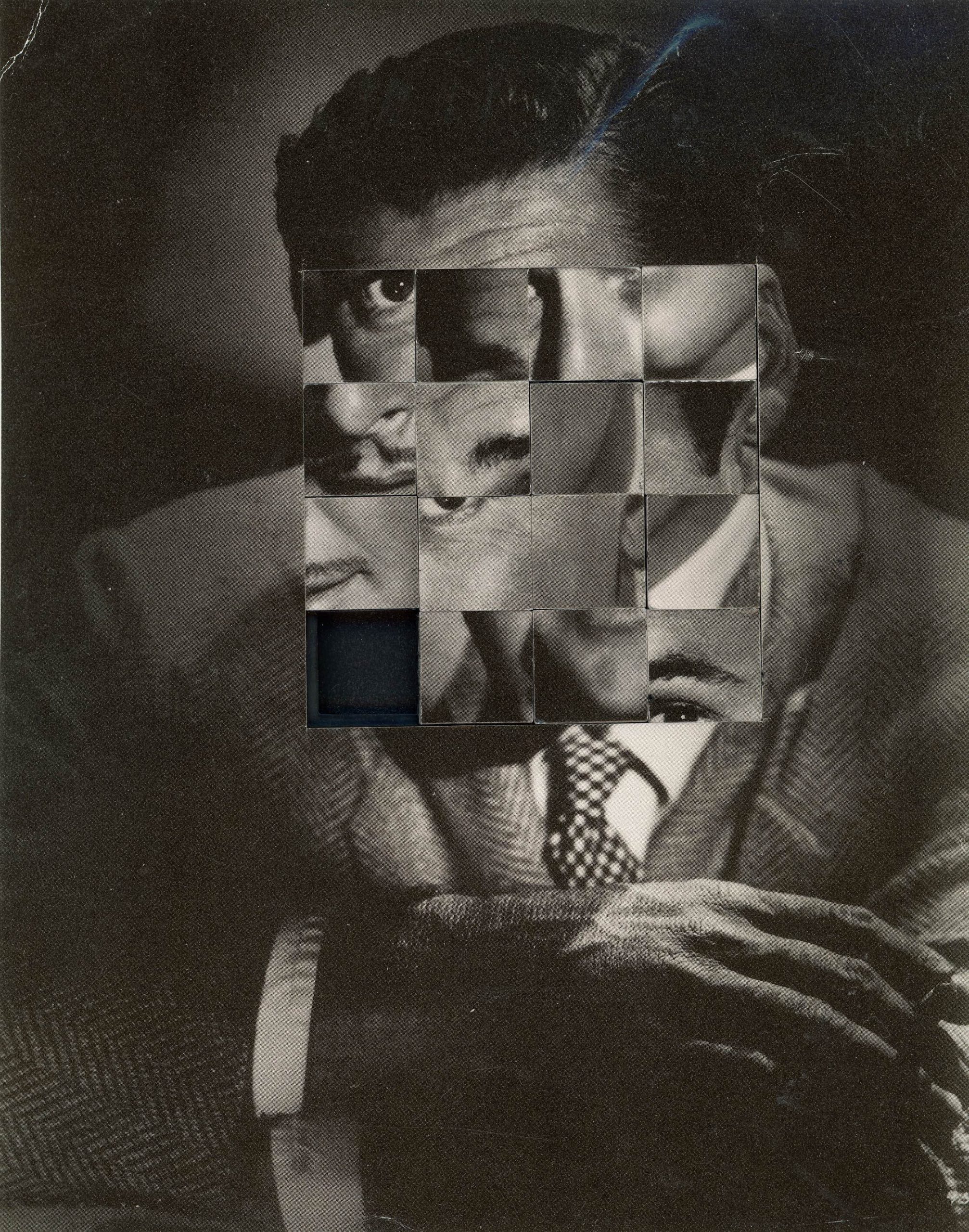

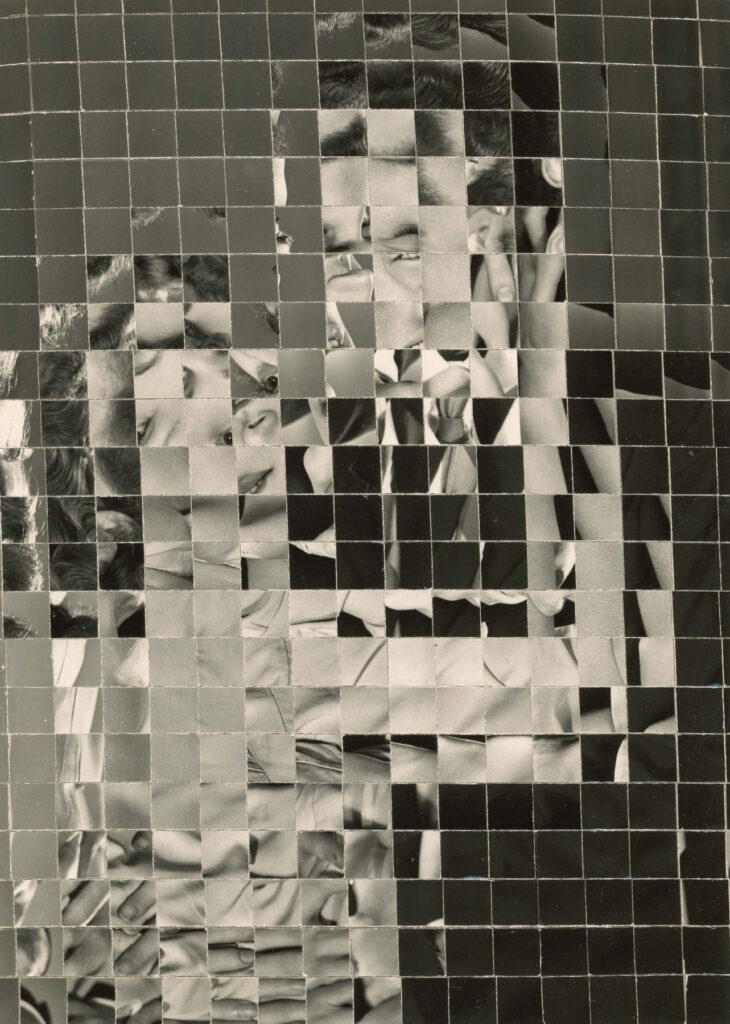

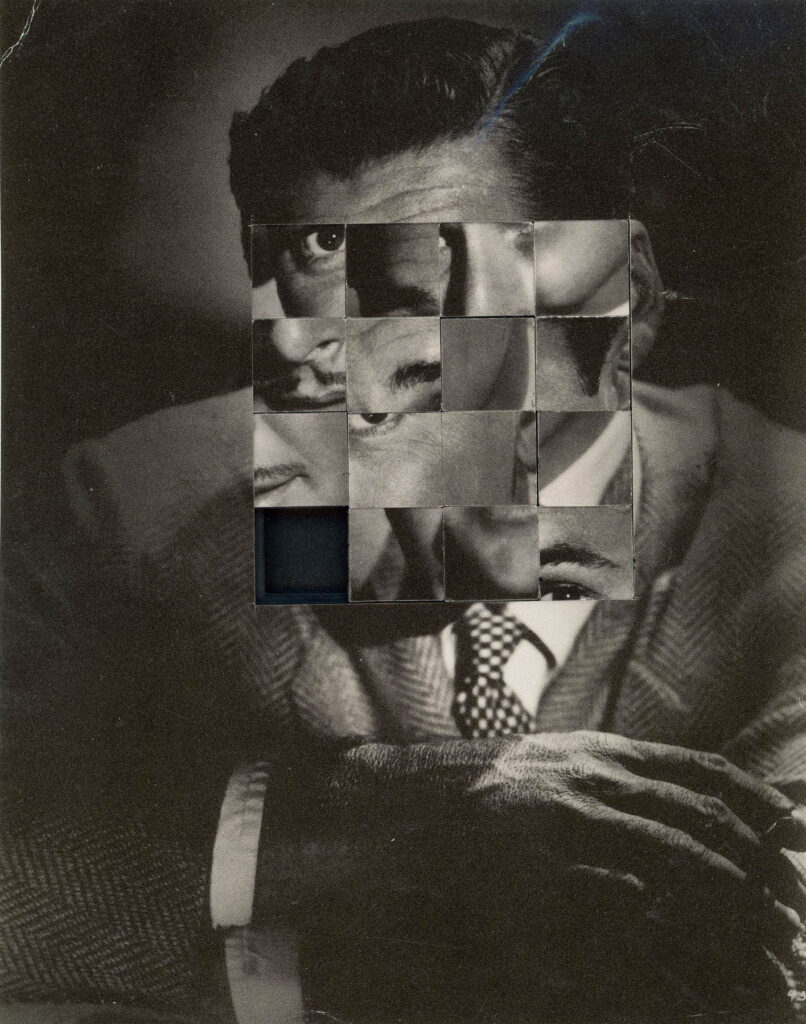

Born in Czarnków, Poland and currently residing in Berlin, photographer Andrzej Steinbach plays with concepts of androgyny and ambiguity in his work. Viewing his works serially, questions about the socio-political role of style, as well as the concepts of identity, personhood, and their representation through photography can be raised. Experimenting with the traditional methodology of portraiture, Steinbach examines how cultural habits and impressions are transposed and communicated through different postures, movements, and clothing.

Also intrigued by the political and revolutionary potential in commonplace objects, Steinbach observes that through appreciating the formal aspects of everyday items and images, artistic practice can be transformed and elevated.

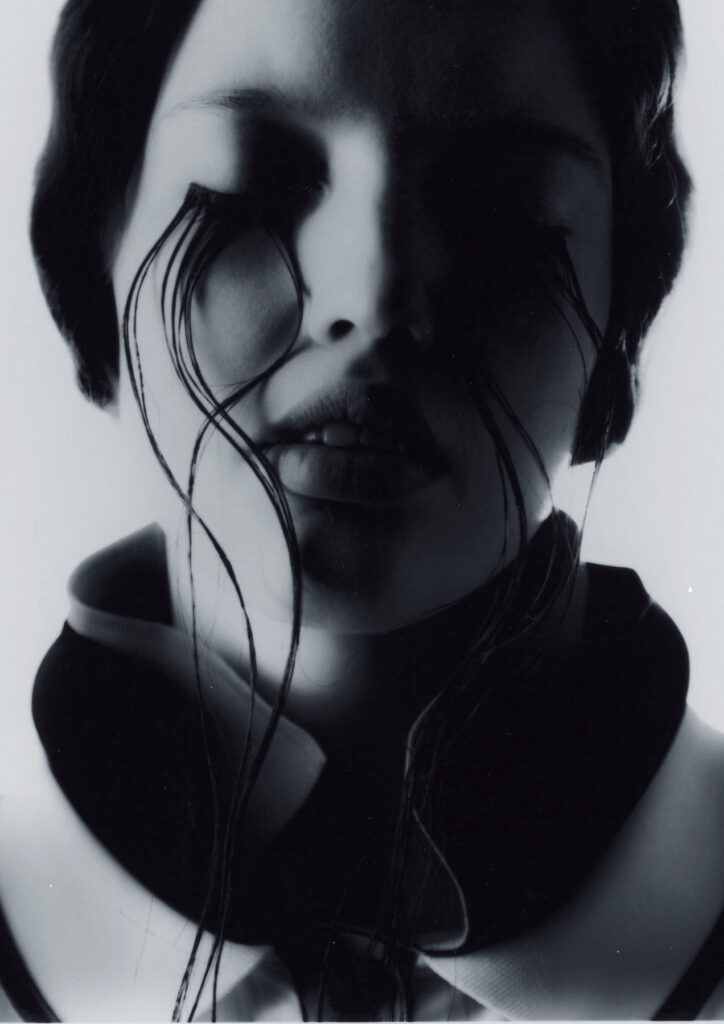

Steinbach often creates a unique sense of disorientation with his figurative work, as his models resist strict interpretations and serve to remind us of the transience and inconsistent nature of relationships and the human condition. His work boldly asks us to confront our performative selves, and to consider how we connect to ourselves and those around us.

Operating within the realm of ambiguity and androgyny, Steinbach’s aesthetic codes are seemingly absent of empathy, and impose a distinctly cold aura onto his subjects. His vision is distanced yet personal, and his work often appears with multiple refusal to provide accompanying interpretations.

At a moment when pre-existing ideas about identity and representation are being redefined, Steinbach’s work continues the dialogue and is a notable reflection on our own ideas of selfhood and our participation in the communities and contexts of which we are a part.

NR Magazine speaks with the photographer to learn more about his own attitude towards his work and what it means to reimagine portraiture.

Born in Poland, you’re now living in Germany and have exhibited your work in cities across the globe. Do you feel a strong connection to any place in particular? Has your background influenced your work at all?

The short answer would be that the sum of places, people and experiences have influenced me – and that applies to all the people I’ve met. My time as a teenager in Chemnitz, East Germany was particularly influential to me, as it was when I first came into contact with sub- and DIY-culture. Coming from a working-class background, the punk and anti-fascist scene in Chemnitz gave me a chance to enjoy these subcultures together with others. At first, I was interested in music and political work, and later I had some small roles as an extra at the opera house in Chemnitz and then I began to work with photography and started documenting my surroundings and social events.

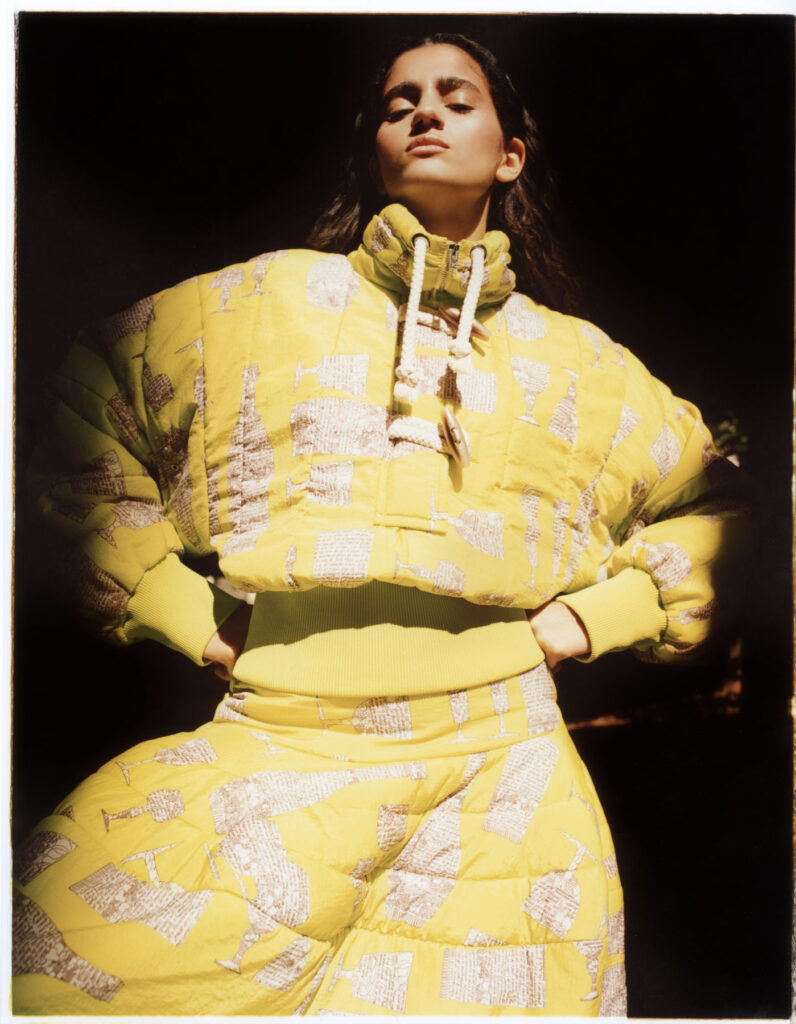

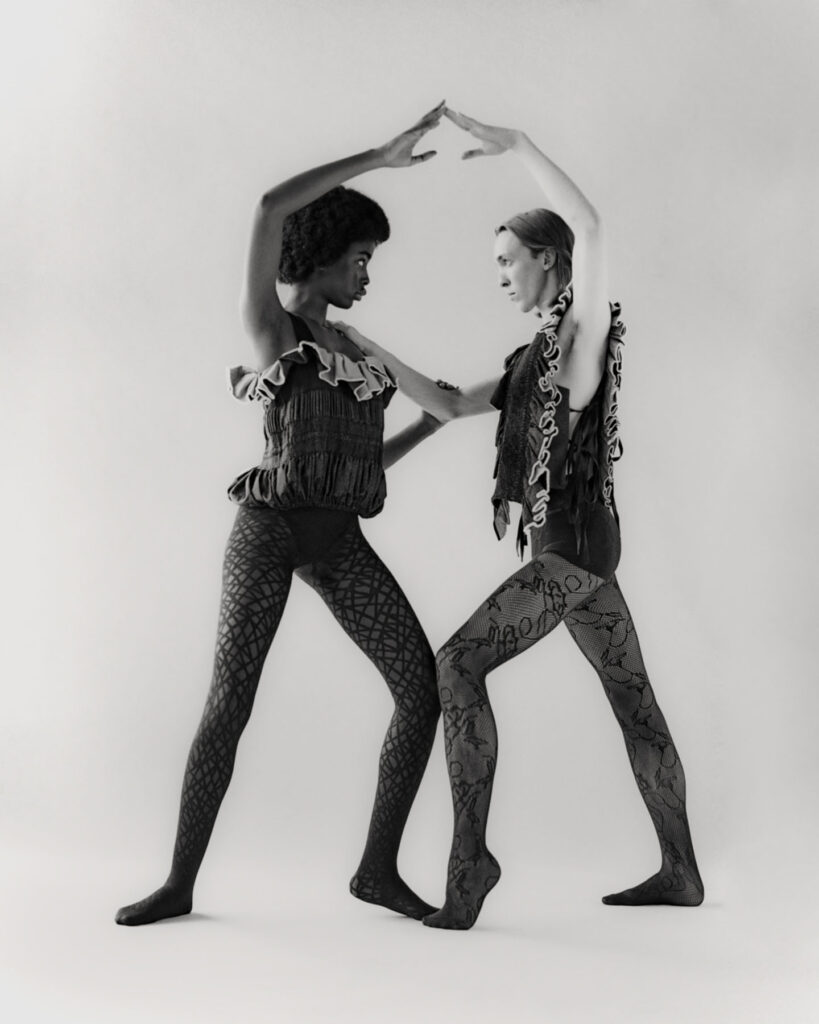

Your series ‘Figure I, Figure II’ explores how the appearance of androgyny has the potential to impact viewers in different ways, as the figures fluctuate between presenting as typically more masculine and feminine. Could you talk a bit more about the aim for this series? There seems to be a focus on exploring the residual identities of the subjects.

When I started working on ‘Figure I, Figure II’ in 2011, I wanted to develop a series that depicted a figure that played with pose, clothing, and habitus so as not to allow a definite image. It took me two years to find a suitable model and a method to create this. An important influence at that time was the book ‘Let’s Take Back Our Space: ‘Female’ and ‘Male’ Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures’, from 1977 by Marianne Wex. I used her binary poses of ‘male’ and ‘female’ body language and turned them into new ‘prototypical’ figures. The prototypical should only have the function to break the idea of the binary and to encourage the viewer to look closer.

Androgyny is being brought to the forefront of a lot of art and fashion recently – we’re seeing more gender-neutral clothing lines and other representations. Has this focus on androgyny and ambiguity always been an interest of yours?

Androgyny can be a welcome tool for some moments to help attack the concept of ‘normal’, but I believe that this also has its limits. My dream is to live in a world where all forms exist without competition and can develop freely. With this, there is no need for an image alternative to the normative, and the idea of what is ‘normal’ itself must be attacked. Consequently, I understand ambiguity not as something confusing, but as a potential that brings us into a resonance with the unknown. In the interplay of the unknown and the familiar lie the productive practices of ‘togetherness’.

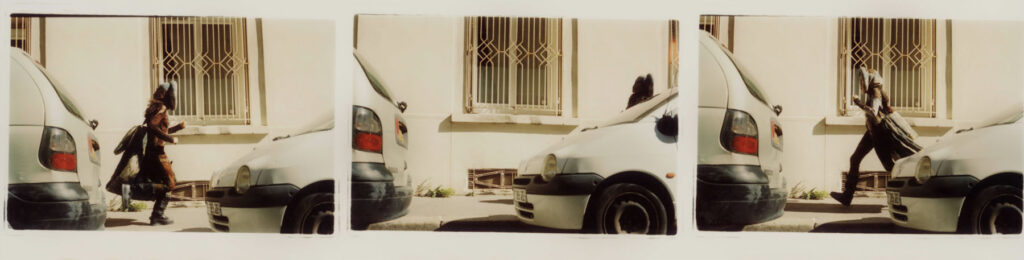

Your work also reflects on questions about alternative forms of style and cultural identity, particularly with the group of five images from ‘Figure I, Figure II’ that depict a Black woman fashioning a T-shirt, step-by-step, into a niqab. What was the inspiration behind this piece?

The work ‘Figure I, Figure II’ consists of two parts: the first consists of 120 images and depicts a person posing in front of the camera – each pose suggests a new role. The second part consists of 64 images and depicts a second person who gradually disguises herself in several sequences with different textiles. She uses ski masks, scarves and the clothes she wore before in the previous sequences to cover her face. As viewers, we see this action in a space closed off from the outside world. The office chair and blinds hint that the room is in some kind of institution or agency. I was interested in showing what it looks like when we gradually hide our face, without depicting the context of this action. In my photographs it’s hard to tell if the reason for covering the face is religious, political, or fashionable. For me, this is where the charm lies – in studying these images. Our own questions and associations with the images are channelled into the work.

These pictures, along with your other work like ‘Ordinary Stones’ and your still lifes seem to explore the political and revolutionary potential in everyday items. Has this always been something you’ve aimed to interrogate with your photography?

This is a wonderful question, as it points to what isn’t always seen in the works themselves. With ‘Ordinary Stones’ I present a series of stones lying on various glass plates and mirrors, and only by adding some recognisable political imagery, do the objects become projectiles. I like it when, in relation to images, we become aware that the context redefines our interpretation. If we think in a productive way, then the creation of new perspectives can be found in the old, the ordinary and the familiar. You could argue that my socio-political attitude isn’t revolutionary, but rather committed to the ideas of reform.

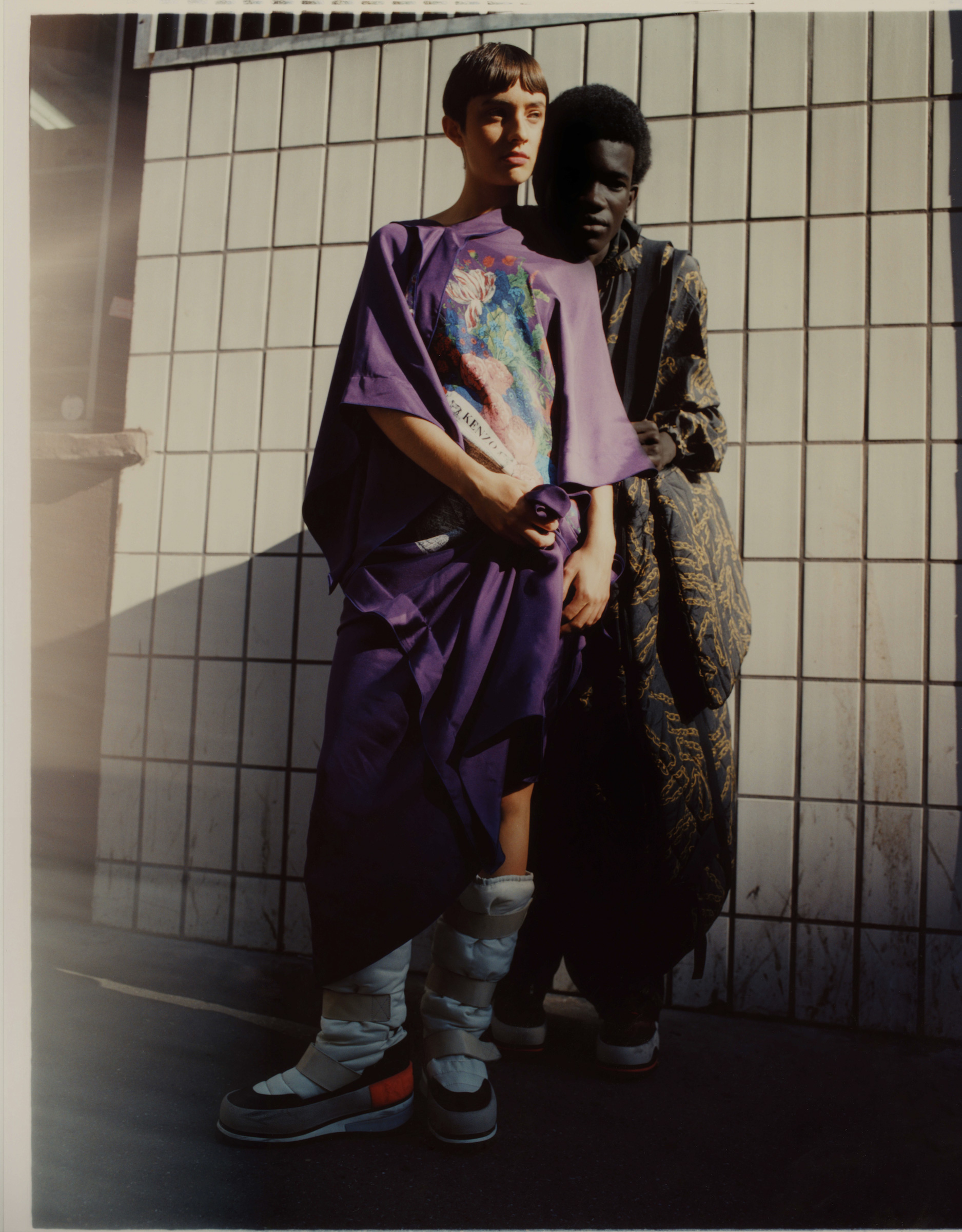

Your series ‘Gesellschaft beginnt mit drei (Society Begins with Three)’ was titled after an essay by the German sociologist Ulrich Bröckling – could you talk a bit more about this inspiration?

In his short essay, Bröckling beautifully describes the interplay and relationship between a triad of individuals or political groups. The triad functions as the starting point of a model of society in which clear power structures can be disrupted. Opposing relationships can be undermined by the third party and renegotiated again and again. When I was thinking about my next piece after ‘Figure I, Figure II’, it quickly became apparent that I wanted to make a series that depicted several people in relation to each other. In doing so, I focussed on the concept of the group and family pictures. Usually, the people who are posing stand to face the camera, and show not only themselves, but also their position in relation to the others in the picture. I wanted to create a group picture from three figures in which each person poses at least once in a separate position. I then included three different uniforms – construction worker clothes, a suit, and casual clothes. Each uniform was then worn by each person at least once.

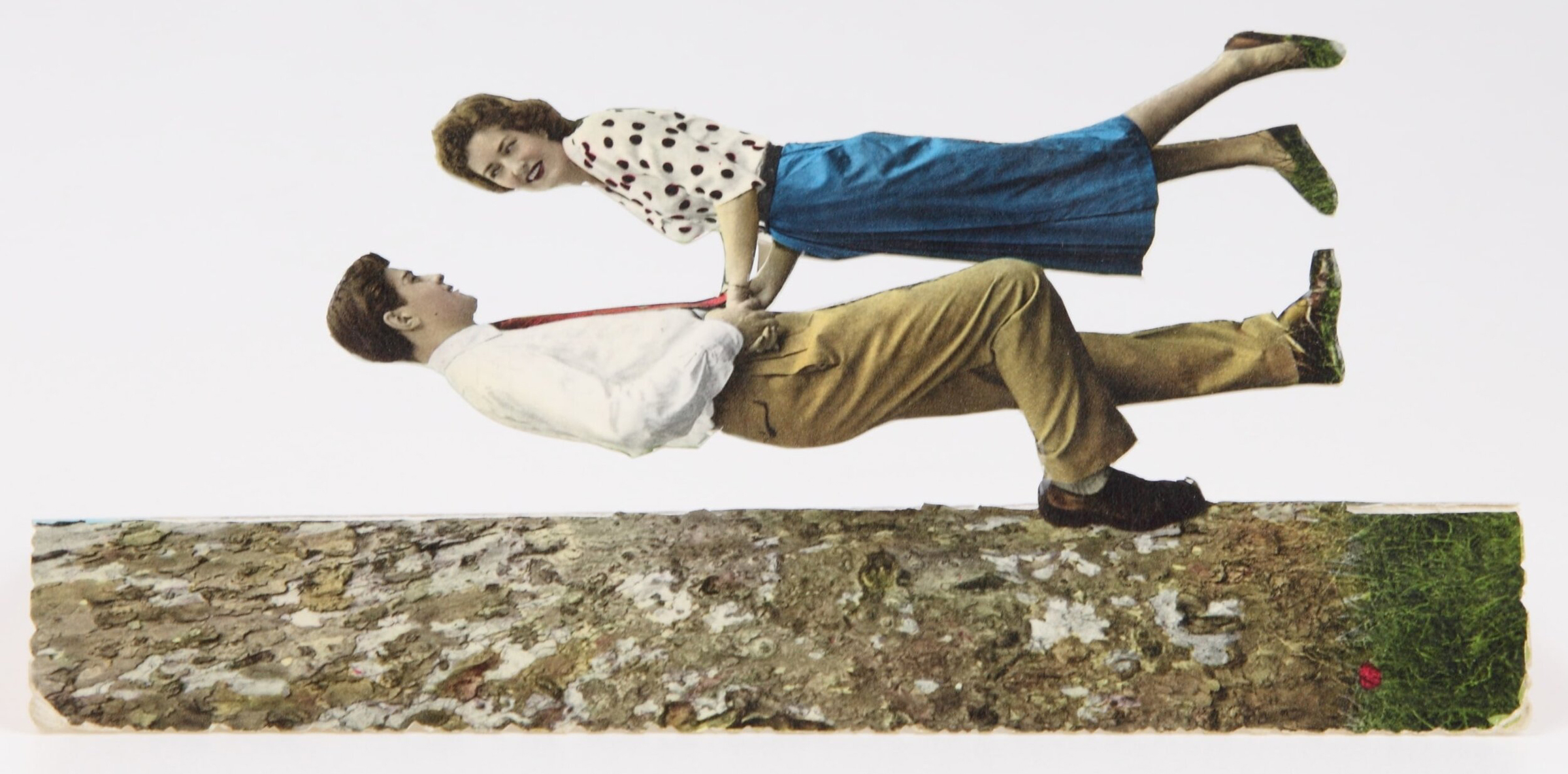

This series subverts the traditional format of a group portrait by having the models cropped partially out of frame and having them switch clothing and positions. What attracted you to exploring these inconsistencies of relationships and resisting homogeneity?

I ended up developing a group portrait of 35 figures using only three people. I could have continued adding to this, but 35 seemed like a good number to me. Cropping the figures at the edge of the picture suggests that nobody is alone in the photograph – someone is always standing next to someone else. Society is the main subject of investigation here. The different roles being played, and the changing positions demonstrates for me, the principles of constant renegotiations of relationships with one another. The photographs serve to remind us that there is no concrete picture of society.

What do you want people to take away from your work?

Ideally, to understand the effect that works by other artists have on me. This can sometimes be sensual, other times rational and other times even educational. When I started getting into art and photography, I learned how to create images for the world. I discovered later that I find it more exciting to find worlds within pictures.

Do you confront aspects about your own self through your work?

Aspects of yourself always flow into your work – I think that’s true for almost all art. I make my art primarily for others and for the sake of art itself, but I can only be confronted by something if it comes from outside myself – something unfamiliar. That’s why I love to engage with the work of others. I get to know myself more through the work of others than through my own.

How do you feel identity and ambiguity interact in your work?

This is a very complicated but important question. I would say that aspects of identity are brought into my work by the viewers themselves, as they always differ according to who is looking at my work. Ambiguity comes from a disappointment perhaps, but it’s a crucial part of the concept of ‘togetherness’.

How would you define identity in the present day? What does it mean to you and your work?

Identity has become such a big word nowadays. I don’t feel quite confident enough to give my own definition. We live in a time where so much is in motion, and I’m curious about where this journey is taking us. I wouldn’t want to think too much about the term itself, but rather about the effects that the discussions around identity cause today. In terms of its significance to my work, I can’t tell at the moment. I have a sense of the scope of the term and how it will affect the way people read my work. When you look at my work, there is no specific points of clarity. Personally, I find the concept of resonance more interesting.

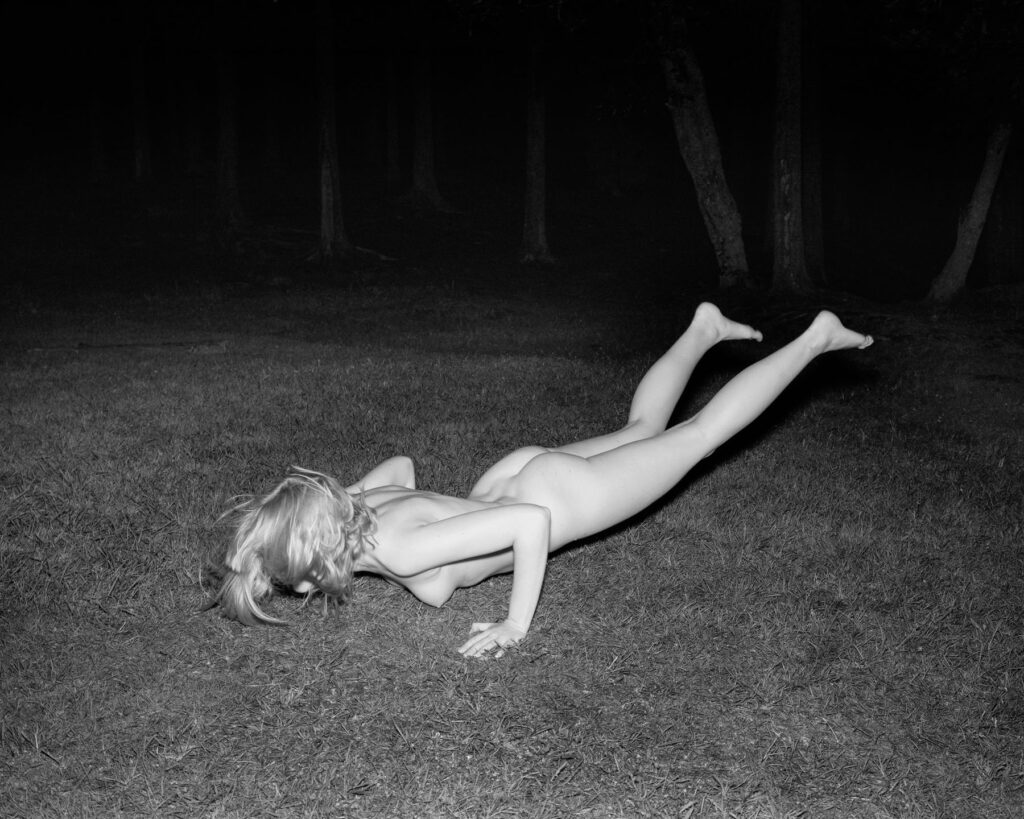

What do you enjoy most about working with portraiture – specifically with a black and white aesthetic?

What interests me most about portraiture is orchestrating the figures. I see my process as being similar to directing. There’s an interesting contradiction with my work and how I use my models. I want to depict figures that are absent and ambiguous, but at the same time are sites of great possibility. One person cannot stand for everything, so the selection and constant addition of new figures to expand this world I’m trying to create helps me deal with this problem. As long as I live and work, things will always change, new ideas will form, and old ones will be re-evaluated. This brings me back to my belief that cultural images and ideas are always evolving.

For my photographs, I work with both a black and white and a colourful aesthetic, depending on the topic of a piece. Colours draw the eye to specific things that grey tones can’t – I just see what fits best with each project.

With your piece ‘Untitled (Bat)’ you’ve mentioned that it points to an important aspect of artistic practice: the love for form, turned into a weapon. Could you talk a bit more about that?

Without form, there is only context and narrative. Form without context and narrative doesn’t exist, and if it does, then it just appears to us as decoration. In ‘Untitled (Bat)’ I present a metal rod that had been used as a weapon. I wasn’t interested in the weapon as such, but rather the form. It’s a metal rod from a shopping cart of the supermarket chain ‘hit’, and at its bottom end has been duct taped. It looks similar to a regular metal pipe, but I was fascinated by the relationship between form and function. I think this is an essential relationship when discussing art.

What is your approach to working with photography compared to other artistic mediums like video and installation?

My approach is always affected by the rules and limits of a medium itself. I believe that every piece of art must operate moving back and forth between the boundaries of a medium. Depending on the topic and project, a project can challenge and break these boundaries, as well as working well within them.

Are you working on any projects at the moment? Where do you see your practice heading?

I am currently working on several pieces at the moment. One project deals with food from industrial production, which I’m exploring as an expanded image of humanity. It has always been possible to understand and interpret social relations from food. I’ve also begun to explore the illusion of eroticism in analogy to macro-photography, but I don’t want to reveal too much. In short, I’m continuing my practice and delving into different ideas. I enjoy straying from the path and seeing where I end up.

Credits

Images · ANDRZEJ STEINBACH

www.andrzejsteinbach.de