What It Means to Be a Silent Witness

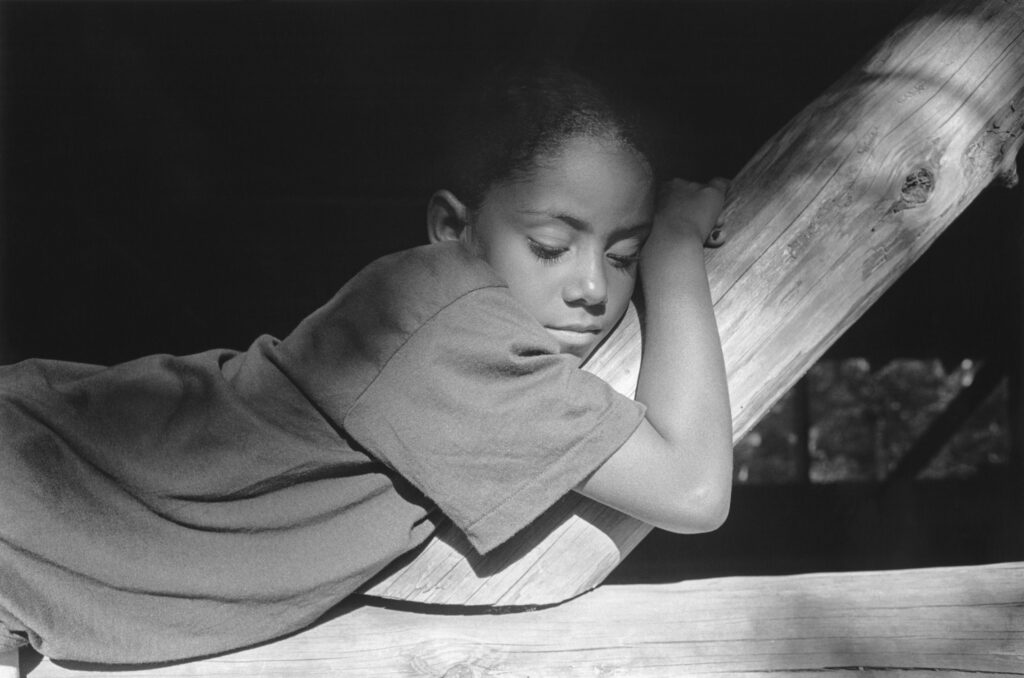

“A child’s perspective is uniquely unbiased… Witnessing through a child’s eyes is an offer, it’s a pure way to ask the audience to reconsider where their own ideas come from.” Akínọlá Davies Jr. maintains a relationship with film that is essentially sentimental. Guided by a restless curiosity, his lens searches for the alchemy of the mundane—a form of silent witnessing that refuses to turn away from the tender textures so often pushed into the oblivion.

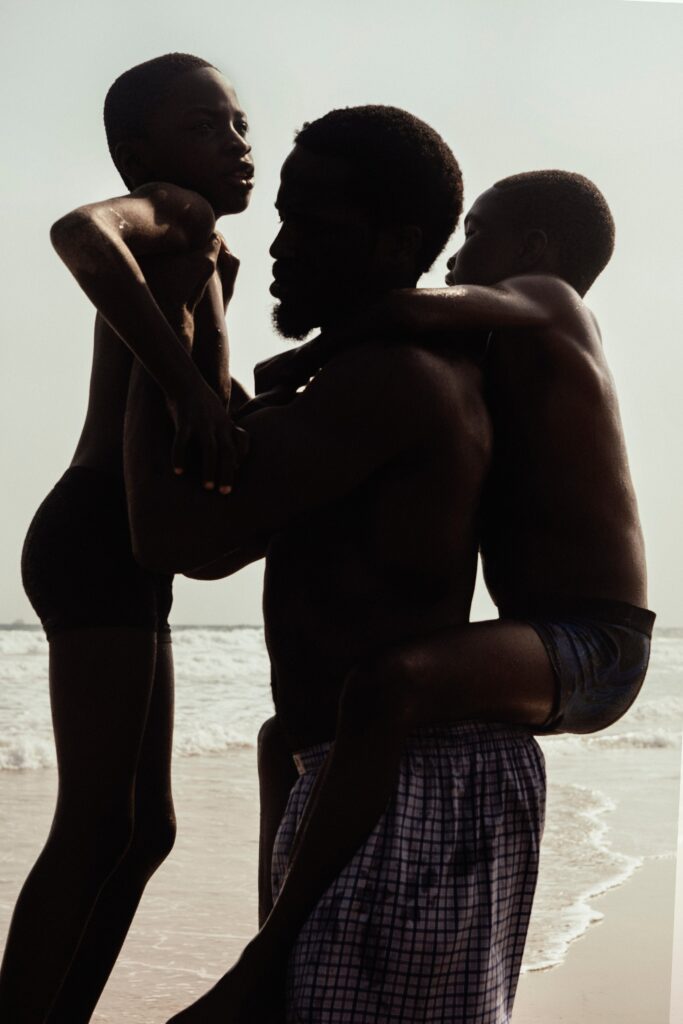

His debut feature, My Father’s Shadow – co-written with his brother Wale Davies – is a cinematic milestone. Having made history as the first Nigerian feature ever invited to the Cannes Official Selection, it arrived on the world stage with an urgency that was immediately recognized, earning the prestigious Caméra d’Or Special Mention. It is a vital, generational introspection that bridges the psychological gap between West Africa and its diaspora, confronting the questions we habitually avoid: the weight of masculine performance, the anatomy of grief and the “spiral” nature of culture.

In the friction between a 1993 Lagos election crisis and the intimate silence of a family’s interior, he unearths a humanism that belongs to us all. He treats the act of filming as an act of preservation, believing that “Archive is also a bridge for solidarity; it’s how we learn our similarities and our opposing views.” It is an invitation to look closer, to remember, and to finally see the magic in our own shared histories. From the fashion narratives of Unity is Strength to the spiritual underbelly of Lagos in Lizard, leading finally to the tactile intimacy and international acclaim of My Father’s Shadow, Davies Jr. continues to dismantle the rigid structures of the gaze in favor of a deeper, more poetic truth.

Your journey began long before the world stage of Sundance. Was there a specific moment of visual awakening, perhaps a particular image or a ritual in Lagos, that first made you realize you wanted to be a witness to the world rather than just a participant in it?

I think my entry into film was actually quite serendipitous. I grew up watching films, of course, but my desire to actually enter the industry was a consequence of witnessing my best friend’s family life while I was in boarding school. I used to go home on weekends with different friends, and this one particular friend’s father was an editor for commercials and his mother was an artist. They lived this incredibly bohemian life with his two brothers, and I found that entire family dynamic so seductive. I was captivated by the idea of how one achieves that lifestyle. When I asked what his father did and learned he was an editor, I decided right then: “Okay, I want to edit. I’m going to try and edit films.”

During university, I took a filmmaking elective and I truly loved the process of editing; it was my favorite part of the entire curriculum. As I moved forward, I met other editors and began cutting my own projects as well as work for others, but I found that editing was an intensely emotional experience for me. It became difficult to maintain the necessary objectivity because I was so deeply immersed in the feeling of it. That led me to experiment with other roles,I tried being a videographer, I worked in costume, I tried production design.

In terms of cinematic influences, there are a few films that left a significant imprint on me, though I’m not sure if they were the direct catalyst for me wanting to direct. I vividly remember Mustang, the French-Turkish film. I remember falling in love with the visual language. It’s such a tragic film, yet it carries this optimism toward the end. I was profoundly moved by the perspective of the young protagonists; it reflected a certain brand of rebellion within a culture that people love deeply, yet they are struggling to find their footing within it in a modern context. Stories like that were incredibly important to me. I’ve also found myself deeply aligned with the ‘gentle supernatural’ you see in Mati Diop’s Atlantique. There’s a way she, and even Ousmane Sembène handles African narratives. I wanted to move away from those tired post-colonial shots of urban hustle and instead find a dignified representation that felt authentic to the Lagos I remember.

You began your career assisting photographers like Alasdair McLellan and Tyrone Lebon, as well as working alongside figures like Jamie Hawkesworth and Dexter Navy. Were there specific moments on those sets where you realized that a director’s job isn’t just to look but to protect the intimacy of a frame? Are there cultural figures whose way of seeing still acts as a compass for your decisions today?

I definitely view the director’s role as one of protection. While every director has a different approach, I believe the job is to protect the collaborators. As a director, you often have the most agency on set; you curate a group of people who are there because of their merit and their desire to contribute to an idea. My responsibility is to create a safe space for that creativity, to be submissive to the idea itself and to ensure everyone feels empowered to contribute, whether they think an idea is relevant or not. There is no such thing as a useless idea if it serves the work. In fact, it is this collaboration that helps protect the intimacy too.

In terms of a compass, I look to someone like David Lynch. Watching documentaries on his process, you see a man completely committed to the art first, protecting the work from irrelevant concerns like shot lengths or industry expectations. There is also Terrence Malick, who possesses a level of freedom and rebellion in his process that is entirely unique. And, of course, Andrei Tarkovsky, his work fundamentally changed how I think about image-making. He treated every frame like a painting and remained deeply submissive to his themes, ensuring the language of the camera and the language of the story were in total harmony.

On a different note, in terms of sheer inspiration, I have to mention Captain Fantastic. I thought it was the most “rock n’ roll” experience for a film; I was obsessed with how masterfully it handled the performances and the raw nature of the protagonist. I remember seeing it in Beirut when it came out and being so moved I actually messaged the cinematographer. It’s those kinds of works that stay with you.

You’ve expressed a desire to shed the auteur label in favor of capturing the sensuality of living. Looking back, did the industry’s obsession with a static, perfect look force you to develop a more radical protection of the feeling, those unpolished and tender moments that fashion often airbrushes out? What specific sensibility from fashion, perhaps the ability to tell a story through a single texture, do you wish to see more of?

To me, filmmaking is entirely a collective effort. I don’t believe in the “Maverick” or the idea that one person is more special than the rest. The depth of the work comes from the willingness of everyone involved to contribute to the process. While there is a natural hierarchy, some people lead and others follow, everyone has a vital part to play in the ecosystem. Without that shared contribution, the material lacks the depth and the “feeling” I’m constantly chasing. I’m far more interested in that group energy than the label of an auteur.

Your 2017 film Unity is Strength for Kenzo was a significant precursor to your feature style. Working with Ruth Ossai and Ibrahim Kamara, you captured an inclusive beauty in the Igbo heartlands that felt radical for the time. How did that era, specifically the process of archiving local rituals through a fashion lens, prove to you that high fashion sensibilities could coexist with the grounded?

I love that reference because that project remains one of my favorites. I felt incredibly encouraged to be as free as possible. I’ve always been obsessed with subversion, the idea that while we might speak the same language, we use different semiotics to deliver a message.

What Unity is Strength demonstrated was that a setting might look “rural,” but if you frame it with a specific intentionality, it can feel futuristic or even ancient. Rituals and traditions pre-date modern culture, so I wanted to reintroduce these existing elements in a way that felt contemporary without “doing too much.” By introducing Kenzo, music, or graphic elements into a community of people simply having fun, the atmosphere shifts into something almost sci-fi.

Ultimately, we are always in a conversation between the past, present, and future. It all comes down to how the viewer frames what they are seeing. Someone else could film the exact same scene and make it look stereotypical or archaic, but I find an extreme magic in the ritual of the mundane. When you treat the everyday with that level of respect, you can find a very specific kind of alchemy.

You have stated that to be an artist is quite a privilege and to exist in privilege is quite political. In the context of the Nigerian diaspora and the global film industry, how do you navigate that privilege to ensure your work remains a site of resistance rather than just consumption?

That is a profound question. For me, it comes down to investigating the depth within an image and questioning what that depth allows the image to serve. I appreciate aesthetics, but I believe aesthetics must be modern enough to serve more than one purpose. If an image is purely aesthetic, beautiful as it may be, it exists only for that fleeting moment. However, when you layer an image with various cultural references and histories clashing together, it becomes democratic. It becomes a space where everyone can see an aspect of themselves. This allows a single, textured image to be reinterpreted by a multitude of people, making it far more dynamic than an image that simply fulfills a decorative purpose.

I am very sensitive to the idea of “throwaway” imagery. I want to create work that outlives its initial purpose, whether people recognize its significance now or in the future. In my background, it is vital that we create multi-functional, multi-dimensional images that can be recycled across different contexts. My navigation of privilege also involves a constant questioning of my own “eligibility” to create a certain image. If I feel I am the right person to make it, I then look for collaborators who are even more invested in that image than I am, ensuring the subject matter is filtered through a worldview that honors the community.

As a Black, African, British male, I don’t necessarily have the same excess of opportunity as a white European or American, so I am always thinking about how to speak to my community. It isn’t about being performative; it’s about being inclusive to ensure there is genuine depth in the objects and images we engage with.

Your work occupies a distinct psychological bridge between West Africa and the UK, often navigating the friction between colonial structures and indigenous reclamation. How do you cultivate a visual language that is legible to the traditional while remaining deeply resonant for a millennial diaspora that is constantly negotiating its own sense of belonging?

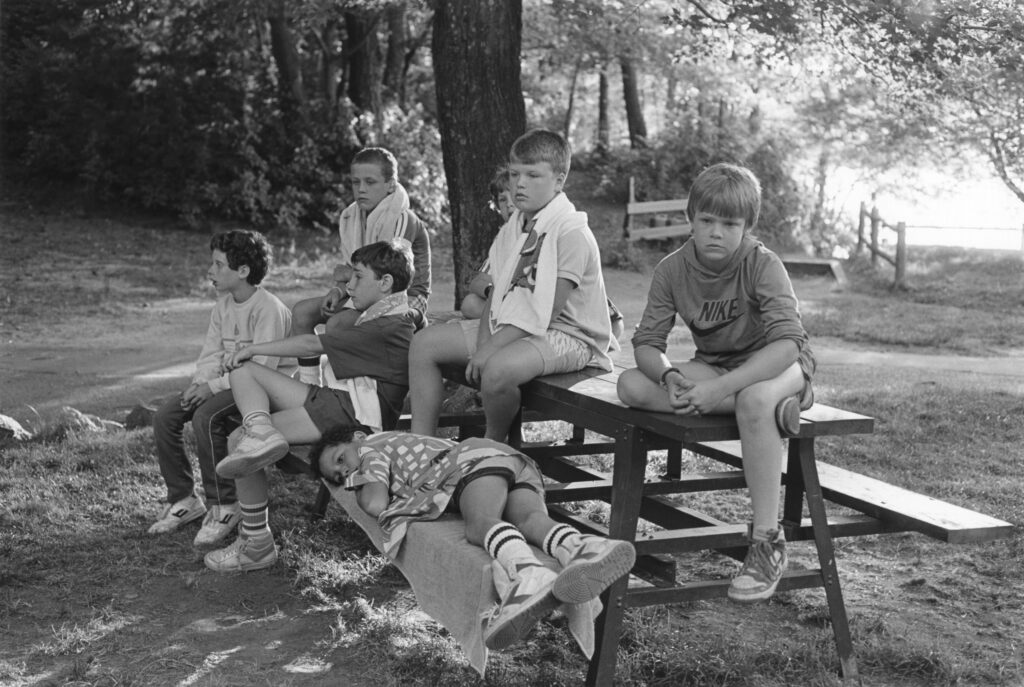

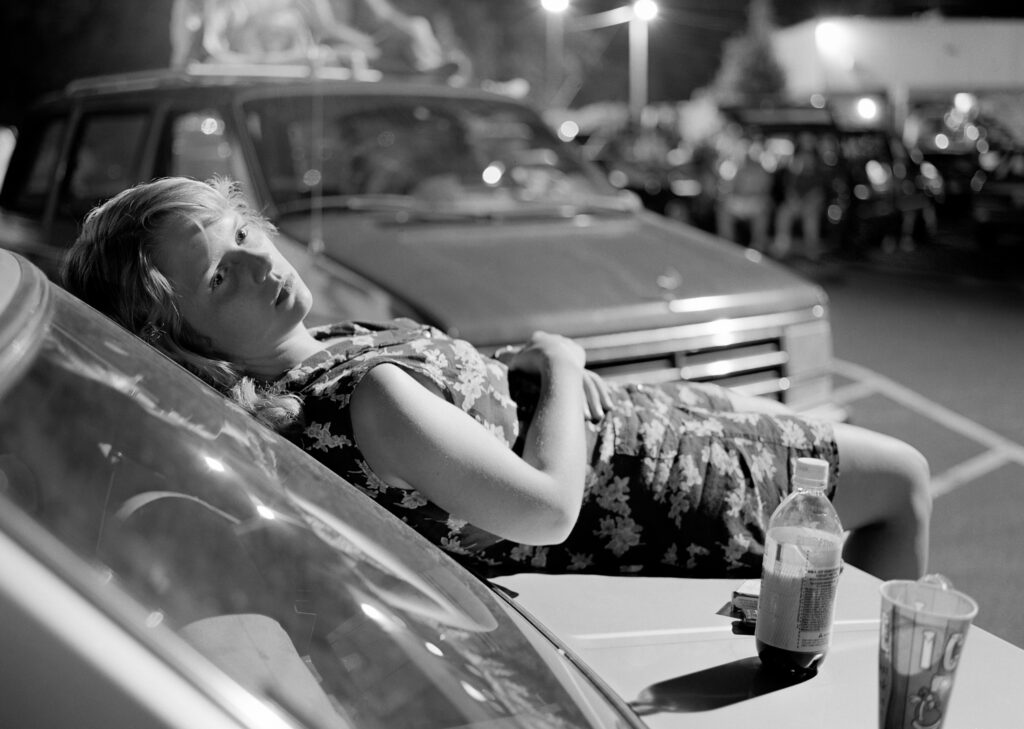

I am very sensitive to how we represent our experiences. Often, representation falls into two extremes: the “exceptional”,like Black Excellence or A-list celebrity, and the other side, which dabs in trauma, exoticism, or “othering.” I realized I was most interested in what exists in the middle. What about the people who don’t see themselves as exceptional or tragic, but are simply trying to get through their day?

I focus on the simplicity of the “middle section” of life, daily rituals like journaling or grocery shopping. This is a celebration of existence; it says that because we exist, our lives are important. I want to honor a language that celebrates this simplicity without leaning into the stereotypes on either end of the scale. The mundane presents a space where you can find magic. For me as an image-maker, there is so much beauty in simple things. I think of the Mona Lisa; aesthetically, it’s a very simple portrait, yet it has such depth because it captures the “horror of simplicity.” It isn’t trying to trick you; it is just a face that suggests the painter saw something profound in the person.

Culture is an evolution, not a static thing. People who try to hold onto culture as something fixed don’t fully understand it. Cultures have always intermingled and mixed. Perhaps planes and globalization have accelerated that, but it has always been a spiral of conversation rather than a linear history. My work tries to document that ongoing conversation, race, masculinity, being British, being European, and being African, all as one continuous, evolving spiral.

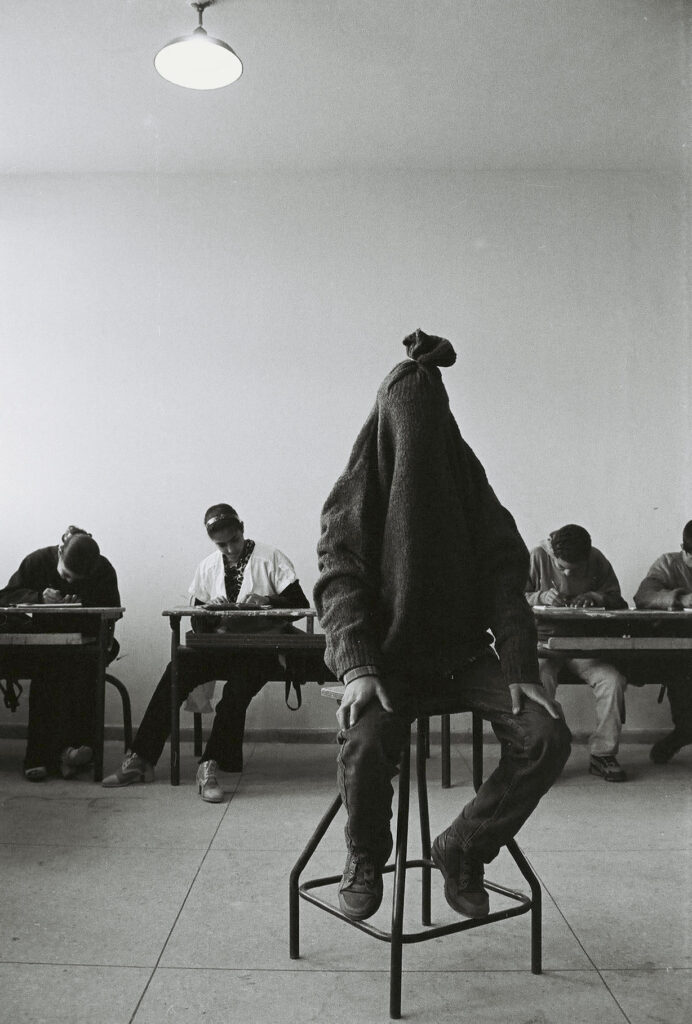

In Boot/Leg for Art Basel, you navigated a multidisciplinary context to explore the alchemy of Black people simply being together. This project seemed to mark a significant artistic evolution, moving away from high fashion toward finding magic in the mundane. How did capturing those everyday rituals and social signifiers prepare you for the tactile intimacy we see in My Father’s Shadow?

These are excellent questions; they really take me back through the work. As I mentioned, I am wary of focusing solely on trauma or the “exceptional.” I want to avoid the exotic lens. By focusing on the middle ground, the everyday rituals,I found a way to celebrate existence without it being quantified by something grand.

In Boot/Leg, capturing those social signifiers and simple concepts with a specific gaze allowed them to feel magical. This prepared me for My Father’s Shadow because it taught me that beauty resides in the most basic interactions. It’s that “horror of simplicity”, the idea that you don’t need to lure the viewer in with tricks. You just show the depth of the person or the moment.

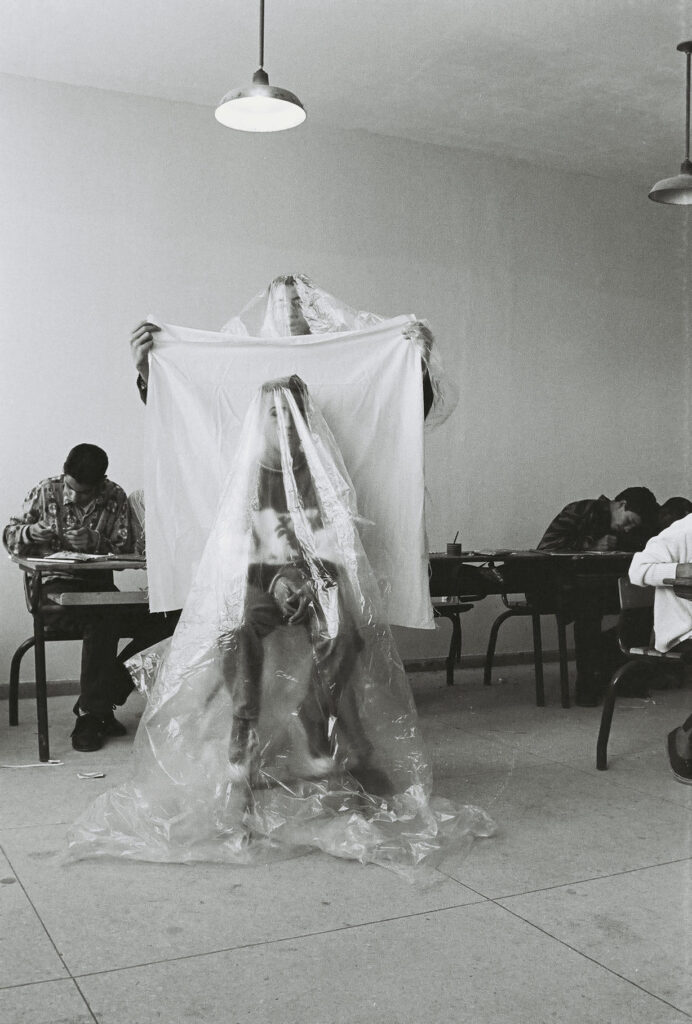

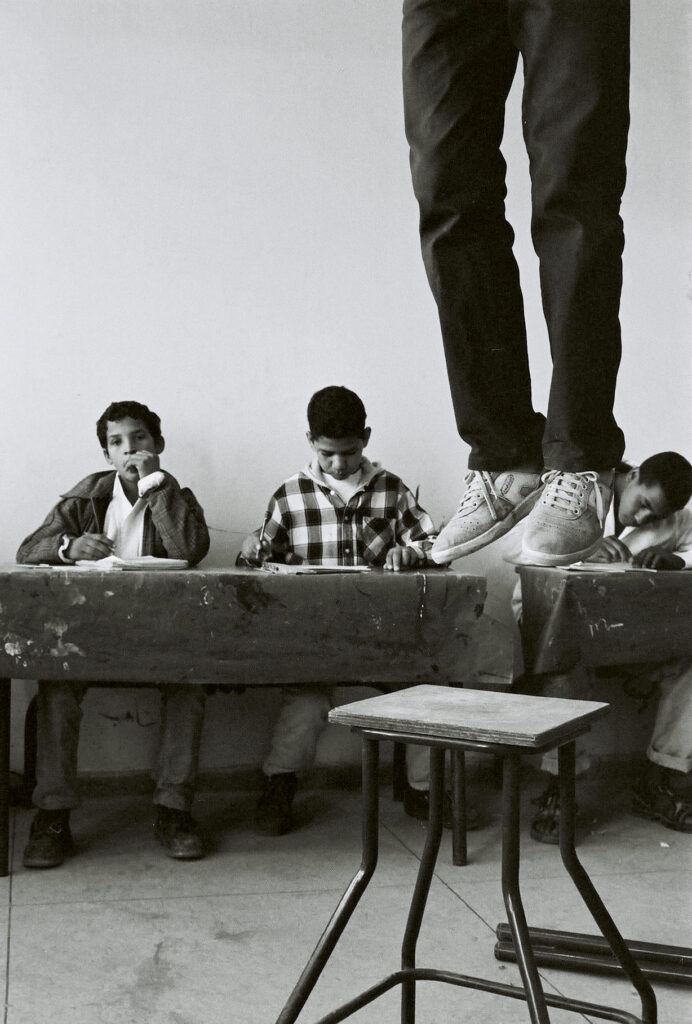

In Lizard (2020), you explored the underbelly of a Lagos Mega Church through an 8-year-old girl. Does My Father’s Shadow continue this exploration of how massive institutions, be they religious or political, shape the secret and internal psychology of a Nigerian child?

I love this link. No one has asked me that before. I wrote Lizard to understand the psychology of a society that allows the events at the end of that film to happen, especially within the context of a mega-church where there is so much wealth and affluence tied to being “religious.”

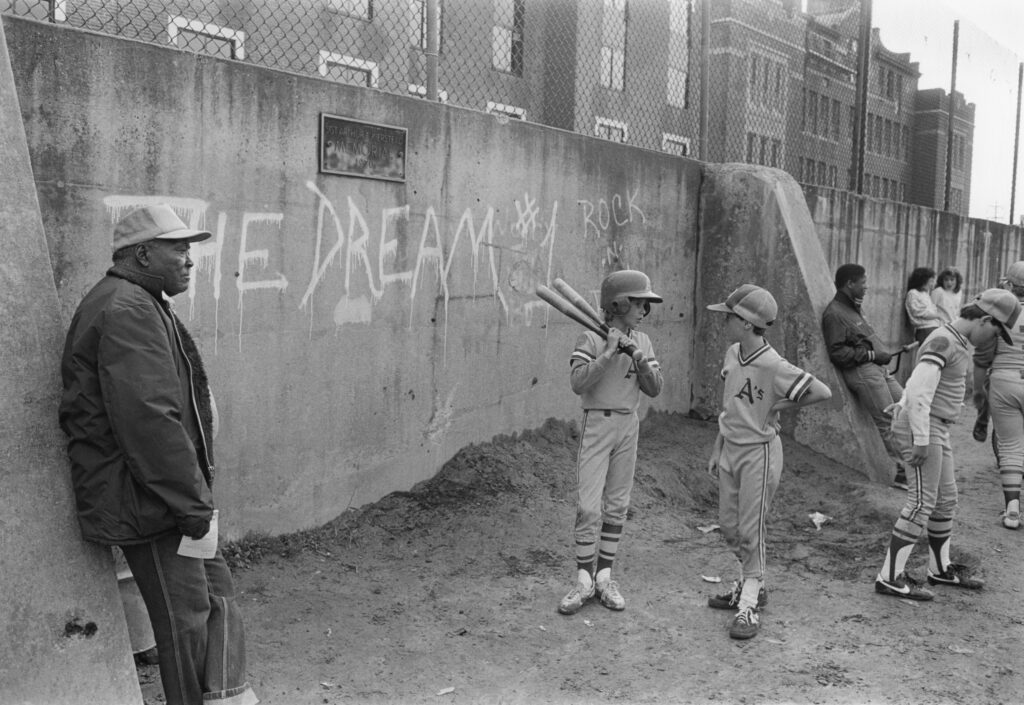

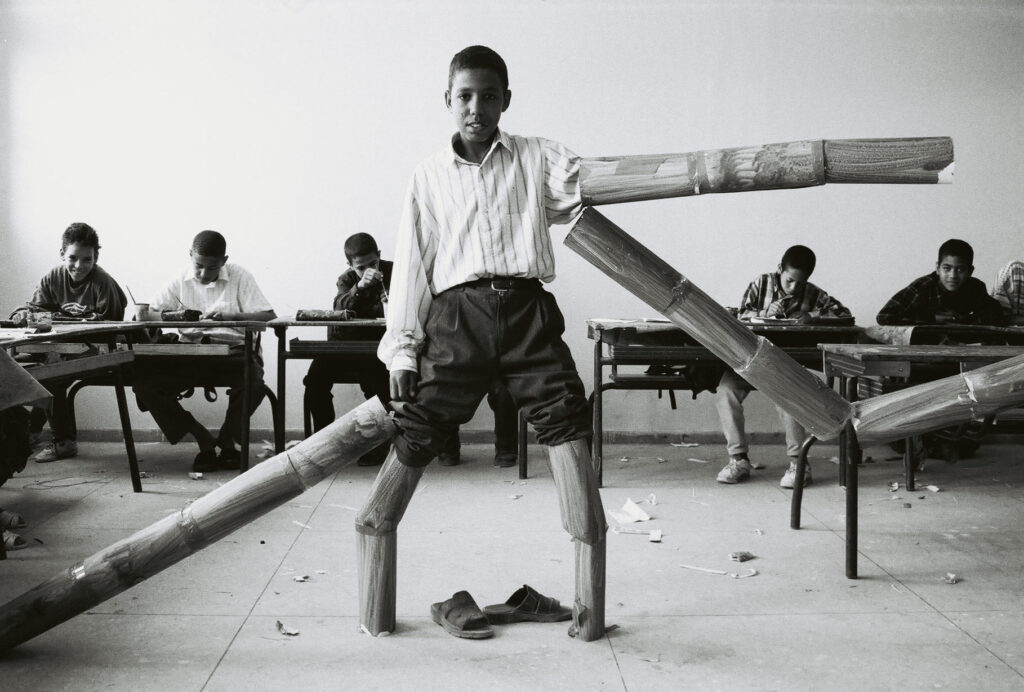

If Lizard is a microcosm of that society, My Father’s Shadow is a much larger investigation of the forces at play. It explores the father’s struggle, having to be away from home, performing a “song and dance” just to get his wages, and the political unrest of the time. The children are the witnesses, wondering what is happening as they move through the city. The two films are definitely in a direct conversation with one another regarding how institutions and communal structures shape a child’s secret internal world.

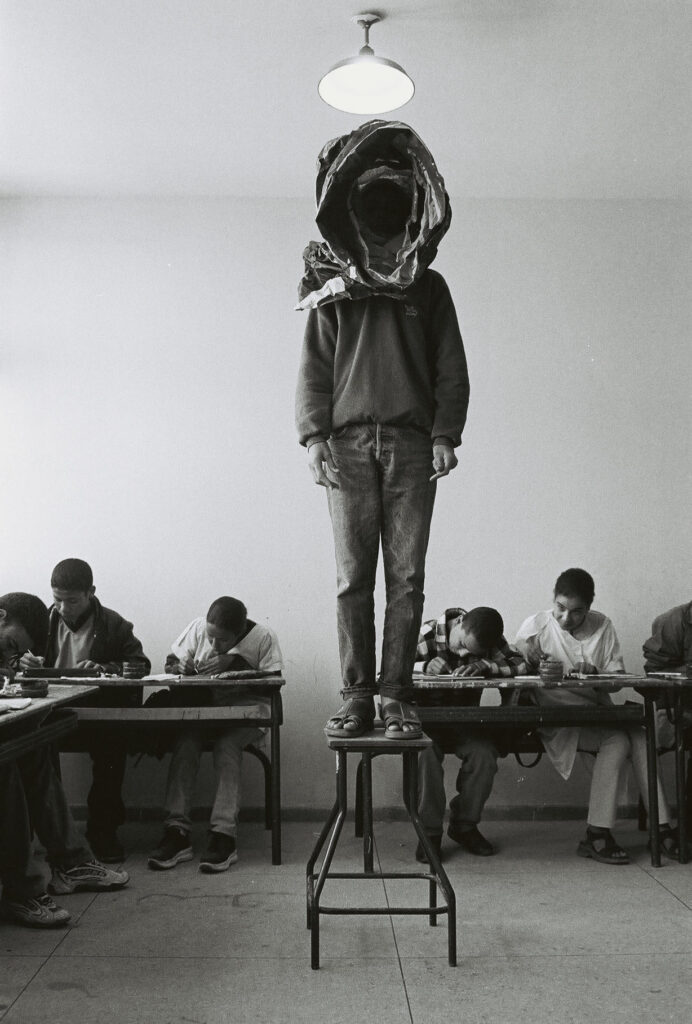

You have a gift for capturing the perspective of children who are hyper aware of adult tensions they cannot fully name. Why is this silent witnessing the most effective way for you to address heavy themes like race and political collapse?

The concept of the “silent witness” is beautiful. I would like to refer to James Baldwin. When he was in Paris during the Civil Rights Movement, he struggled with his contribution until he was told that “the witnesses” are just as important. That stayed with me. We aren’t all “fire and brimstone” heroes willing to sacrifice everything, and I’ve realized that there is something subversive about simply living a long life and becoming a vestige of knowledge, an archive for your community.

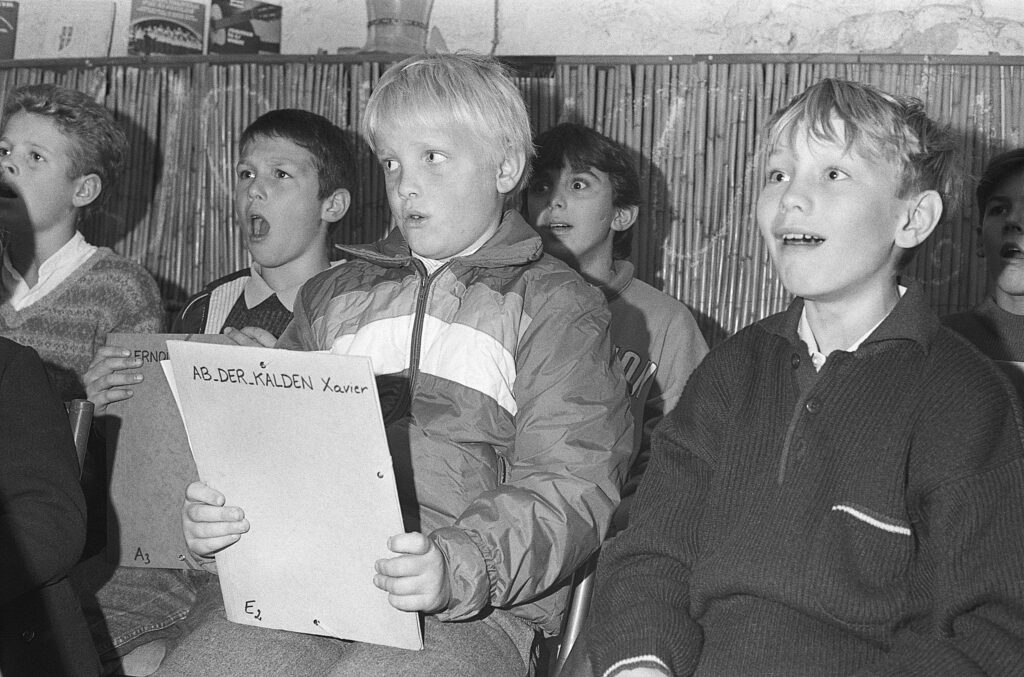

A child’s perspective is uniquely unbiased. They are grappling with themes, politics, and institutions that they have to “learn” just as we did. These things aren’t natural; they are socialized. A child witnessing a situation and thinking, “This is actually quite dumb,” neutralizes the viewer’s perspective. You don’t have to be politically correct; you just say what is on your mind.

For example, someone asked me about including a disabled person in the film. In West Africa, there are many disabled people, but the infrastructure isn’t there like it is in Europe. I wanted to show that they exist and are an important part of society. I was able to have that conversation through a very small interaction with the children. Witnessing through a child’s eyes is an offer, it’s a pure way to ask the audience to reconsider where their own ideas come from.

A semi-autobiographical tale set over the course of a single day in the Nigerian metropolis Lagos during the 1993 Nigerian election crisis. The story follows a father, estranged from his two young sons, as they travel through the massive city while political unrest threatens their journey home. How did you begin the process of unearthing your own childhood memories of Nigeria then to build this narrative, and what was the creative evolution required to transform such a specific personal history into a mirror for the universal complexities of the Nigerian family today?

I don’t carry that responsibility alone; it has been a profoundly collaborative journey. My brother, Wale, is the lead writer, and our shared history is the bedrock of the film. Outside of the professional sphere, I’ve been in therapy for over a decade, which has been instrumental. It has allowed me to vocalize thoughts I might otherwise suppress for fear of them being “problematic.” Therapy doesn’t “fix” you, but it provides a toolkit to explain how you feel, allowing for a level of introspection that is vital when dealing with such personal material.

I’ve become very conscious of what I’m passing on, how my behavior affects those around me and what I might eventually pass on to my own children. Making My Father’s Shadow was an act of bridging the gap between my brother and me, creating an artistic precedent for our family moving forward. Even if we never make another film, this stands as a legacy for previous generations, for us now, and for our nieces and nephews in the future.

The film centers on the idea that choosing to care for family and choosing love is the ultimate revolutionary act. It goes beyond the stereotypical “I love you” and moves into the territory of: “I love you so much I want to be a better version of myself so I don’t pass my own grief and baggage onto you.” It’s about striking a balance, even while recognizing that we will inevitably mess things up.

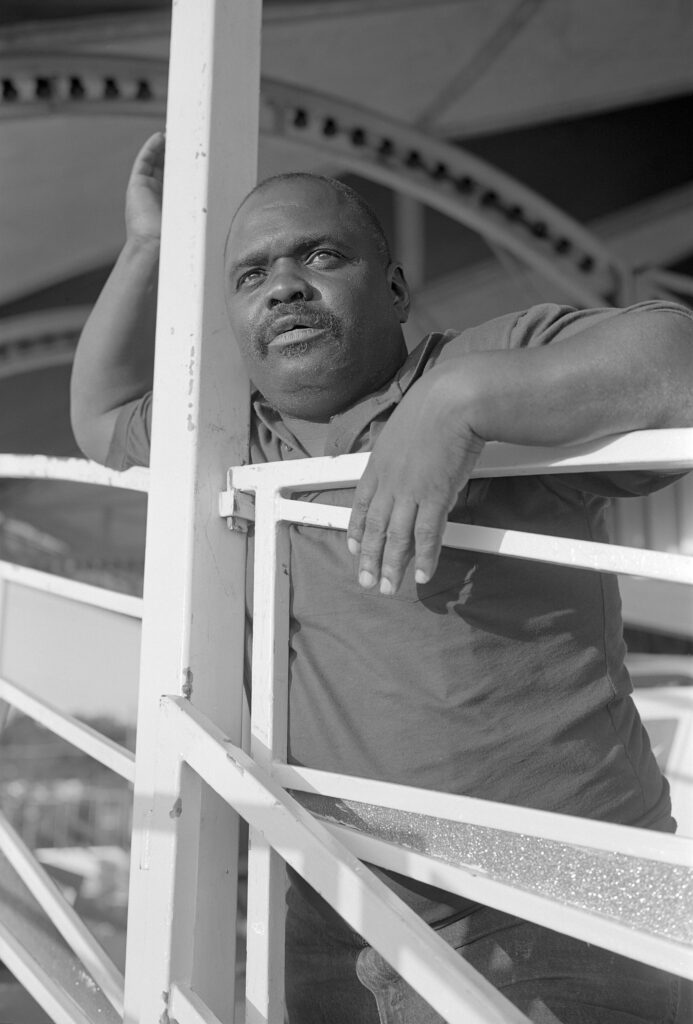

The “absent father” becomes universal because it’s an exploration of our own lived reality. We lost our father when I was a baby, and our grandfather shortly after. I was raised by my mother and a matriarchy of grandmothers and aunts, so we always had access to our emotions. Yet, as you navigate the world as a man, you still have to grapple with the characteristic traits of traditional masculinity, the “provider” or the “womanizer.” This film is an inward reflection on how we hold that form of masculinity accountable. It is a conversation with grief and memory where we say: “We see it, we can call it out, and we are trying to be better.”

Ultimately, I want the audience to project their own concepts of memory into the film. I want to trigger a curiosity that allows for a dialogue between my story and their own lives. If the viewer sees a reflection of their own family complexities within our specific Lagosian setting, then the narrative has done its job. It’s about keeping that conversation open rather than closing the loop.

You’ve spent a decade recording conversations with your mother to archive your family history. How did these conversations shift your perspective from merely telling a story to protecting a legacy?

It began with the simple realization that she is aging. I wanted to archive her voice and her personality while she was of sound mind, so my children would truly know who she is. Beyond that personal anchor, it became a broader necessity. History often picks one static aspect of a culture and recycles it indefinitely, but culture is a constant evolution; it is a conversation that is always moving. People who view culture as static don’t fully understand what they are trying to hold onto.

In an African context, mothers often represent a sacred access point to feeling, nurture, and vulnerability. The older I get, the more the “patina” of the mother-child dynamic wears away, and she starts giving me the real “tea”,the true information. This archiving process is like a Russian doll; you archive, and then a few years later you go back and find even more layers. It made me realize that I am an archive, and my work is an archive. It’s about mixing those layers to create a multidimensional perspective. It’s not linear; it’s a spiral. That realization set everything off for me,it led into my explorations of community, masculinity, race, and what it means to be British, European, and African all at once. Archive is also a bridge for solidarity; it’s how we learn our similarities and our opposing views.

It is a remarkable story that you didn’t know your brother, Wale, wrote screenplays until a chance revelation at Cannes. When you finally read My Father’s Shadow, the first screenplay you had ever read, how did it change your understanding of your own family history?

I’ve always been comfortable with the idea of death, not in a reckless way, but with a certain fearlessness. However, when I read Wale’s script, it was the first time I had ever considered paternal vulnerability. It had never crossed my mind that my father could be unsure of himself or sensitive.

Wale and I actually had very opposing views of our father; he idealized him, whereas I held a lot of anger toward him. The writing process became an explosion of grief and a way to navigate those conflicting feelings. It was formative for both of us because it allowed us to see each other’s vantage points more fully. The process of creating this art allowed us to see one another,and our history,more clearly.

Costume designer PC Williams used your personal family photographs to recreate 1990s Nigeria. How did seeing your dreams being updated and worn by actors in the flesh affect your direction on set?

PC is the unsung hero of this film. Her work is so seamless that people often forget they are watching a period drama. That subtlety is the trademark of a master. It took what was in my imagination and grounded it into a shared reality. Everyone brought their own vantage point,PC was referencing her family while I was talking about mine,which allowed the world to germinate in a vast way.

We spoke a lot about “color therapy”,how certain colors represent different moods or cultural signifiers. We used costume to play into the psychology of the characters; for instance, the contrast between the brothers,one wearing a shirt and jeans while the other is in a more playful T-shirt,gives them immediate depth. The clothes became the uniform of our memory: tailored but loose, reflecting the specific conversation of that time in Nigeria.

You’ve described sound as the emotion of an image. How does the post rock score by Duval Timothy crystallize the specific emotional vibration of Lagos in 1993 and how did your fashion background influence this vibe led approach to sound?

My background in fashion gave me the privilege of being able to identify a rich, textured image,to find beauty first. My cinematographer and I treat every frame like a painting, and I wanted the sound to be a submissive accompaniment to that imagery.

Duval Timothy is incredibly talented; his music has a bittersweet quality that can seduce you and then push you away. I gave my collaborators a specific reference: a piece of fruit that looks normal on one side, but when you turn it around, it’s completely decaying. I wanted the instruments to sound beautiful but occasionally slip out of tune or fall into a dark mood. Duval and my brother both became fathers recently during this process, and you can hear that raw intuition and vulnerability in the score. It feels completely at home with the story we are telling.

As My Father’s Shadow moves into the world, what is the one feeling or shiver of recognition you hope the viewer carries away with them? Beyond the political history of Nigeria, do you hope this film offers a form of grace or absolution for those navigating their own shadows of absence and family grief?

I want people to see themselves in the film and project their own concepts of memory into it. I’m interested in triggering curiosity, I want to hear your “conspiracy theories” about what is happening. If I define exactly what the film is “about,” it closes the loop. I’d much rather someone come to me in five years with a completely different theory.

On a second level, I want people to recognize how connected our histories are. The contemporary history of Nigeria is bizarre and unbelievable, which makes it a fascinating place. There is a massive “brain drain” in Nigeria, with human resources spread across the globe, and there is a reason for that. The participation of the British, Italians, Americans, and Chinese in that history is much closer to home than people think. I want the audience to look past the politics and see the raw humanism.

Having spent a decade on this debut and successfully bridging the worlds of high fashion and narrative feature film, where does your curiosity lead you next? Are you looking to further explore the alien space of the diaspora or is there a new sensory logic or institution you are eager to dismantle through your lens?

I want to travel more around Nigeria, learn about the different tribes, and connect with the diaspora globally. To become a master of this craft, you have to be open and put the time in. Whether it’s documentary, experimental, or commercial, I love the medium of cinema and want it to become muscle memory for me.

Right now, I’m following whatever feels most urgent. I won’t be a young man forever, so while I have this energy, I want to deal with the things that feel pressing, exploring how we decolonize our narratives and re-educate ourselves through a new sensory logic.