Inexplicable Rightness

“I think you want to show the ordinary world, but have it be fresh, and have it be charged, so that we’re not so complacent in our lives, and we notice every day.” A manifesto for his entire practice. Across four decades of work, from the streets of Los Angeles to the sidewalks of Chicago, from the deep South to Parisian metro entrances, Mark Steinmetz has built one of the most quietly radical bodies of photographic work in American culture.

Steinmetz has remained committed to something rare: attention. His black-and-white photographs hold space for uncertainty, for what Robert Adams once called “inexplicable rightness,” for the strange poetry that emerges when nothing is forced to perform. Children pausing between innocence and self-awareness, strangers crossing in a sliver of light, bodies waiting, resting, passing through.

In this interview for NR Magazine, Steinmetz reflects on the formative years that shaped his way of seeing – from a childhood darkroom and early obsessions with cinema and Nabokov, to wandering Los Angeles with Garry Winogrand, to decades of slow, committed observation across the American South and beyond. What emerges is not a theory of photography, but a philosophy of presence: a belief that meaning does not need to be manufactured, only attended to. Steinmetz remains faithful to a more difficult task: to look long enough for the world to reveal itself back.

You began photographing in your late teens, initially as a way to understand and engage with the world rather than as a defined artistic ambition. What did photography make possible for you at that stage, in terms of access, understanding, or a way of being in the world? At what point did it shift from interest to necessity?

I began photography earlier than my late teens. I was taking pictures as a kid, and I had a darkroom around the age of twelve or thirteen, so I was already photographing. I was always interested in photographs. My interest early on may have been more in special effects. It wasn’t until college, when I was about eighteen, and I saw a lot of movies by Michelangelo Antonioni, that I began to think more about the literary aspect of photography, more about the humanities side of it. There was always a component of it being a kind of game, trying to catch things. But as you get older, you start to want to make things more meaningful.

You have spoken about early influences from cinema and literature. How did these non-photographic arts shape your sensitivity to narrative, rhythm, or atmosphere within a single image?

I read a lot of Nabokov. It was very clever and complex. In movies, I looked at Antonioni, but also a lot of film noir, and how gangster movies can operate on another level at the same time. The formal strategies of directors, especially in the thirties, forties, and fifties before color took over, were very architectural. You see a lot of constructed scenes.

After leaving the MFA program at Yale, you moved to Los Angeles and began making your first sustained body of work in public space, a period you have often described as formative and shaped in part by figures like Garry Winogrand. What did that moment—Los Angeles, the street, the encounter—teach you about photography that formal education could not? And as you were absorbing the work of photographers such as Walker Evans and Lee Friedlander, each working within very different social and historical contexts, how did those visual histories begin to inform, or resist, the development of your own way of seeing?

Los Angeles was a difficult time. I was twenty-two. I was restless. It seemed like a simple, superficial place, not a lot of the kind of artistry I was interested in. I was taking pictures, and I met Garry Winogrand a few times. We drove around together, and it meant a lot. I absorbed something from him, especially his manner of being. It showed that an adult could do this kind of work. There is no real career as an artist, but you can survive. There was a way to share it, and Winogrand was well known.

Are there any memories from Los Angeles, particularly with Winogrand…

The last time I really saw him we were photographing at the zoo. He made a body of work there called The Animals. We were there on a weekend, photographing separately, then we met. Toward the end of the day the light was fading, and on the way out Bernadette Peters was there. She was very famous then. She had been photographed by Gary years earlier for the film Annie, directed by John Huston, for which photographers like Stephen Shore and Eggleston were also invited.

She was there with her boyfriend. They had the same curly hair and matching leather jackets. Gary zoomed in and took a picture, and she threw her head back, just like the famous ice-cream photograph. We left. He sat in my car and said, ‘Boy, you don’t know how tired you are until you sit down.’ Later he became sick. He was photographing two months before he died.

The phrase “showing us what we already know” is often used in relation to your work. What does that idea mean to you in the context of your photographic practice? What kinds of recognitions or quiet truths are you most drawn to through photography?

Maybe it’s more accurate to say that it shows what we think we already know. You want to show the ordinary world, but have it be fresh, and have it be charged, so that we’re not so complacent in our lives and we notice every day.

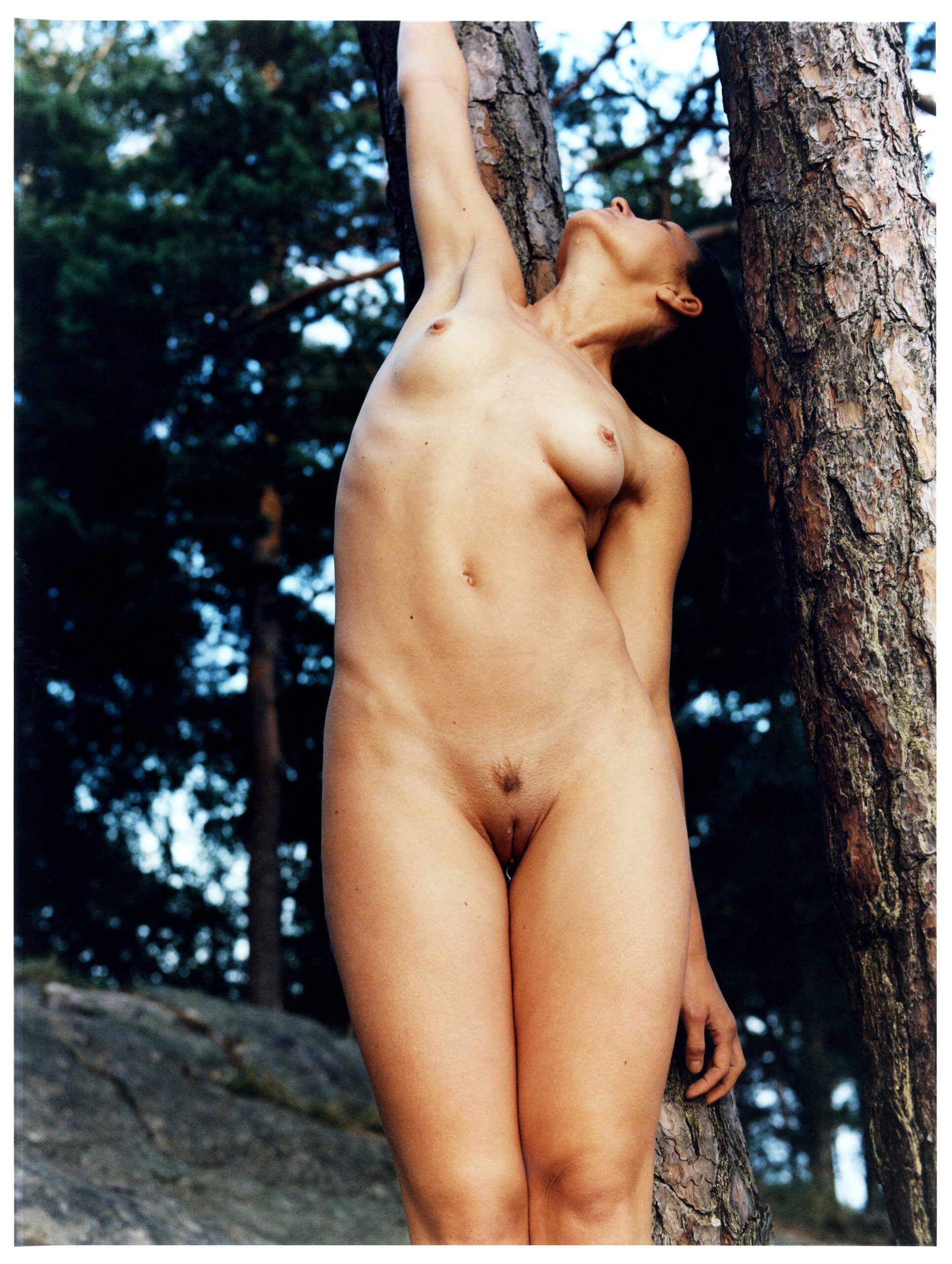

From your earliest work onward, your photographs return to ordinary encounters, small gestures, and everyday situations. What is it, specifically, that you recognize in these moments as worth holding onto?

I’m drawn to moments of poignancy that transcend what we are accustomed to. There is a connoisseurship to photography. It isn’t people holding hands. It’s these people holding hands this way, in this light. Something very specific.

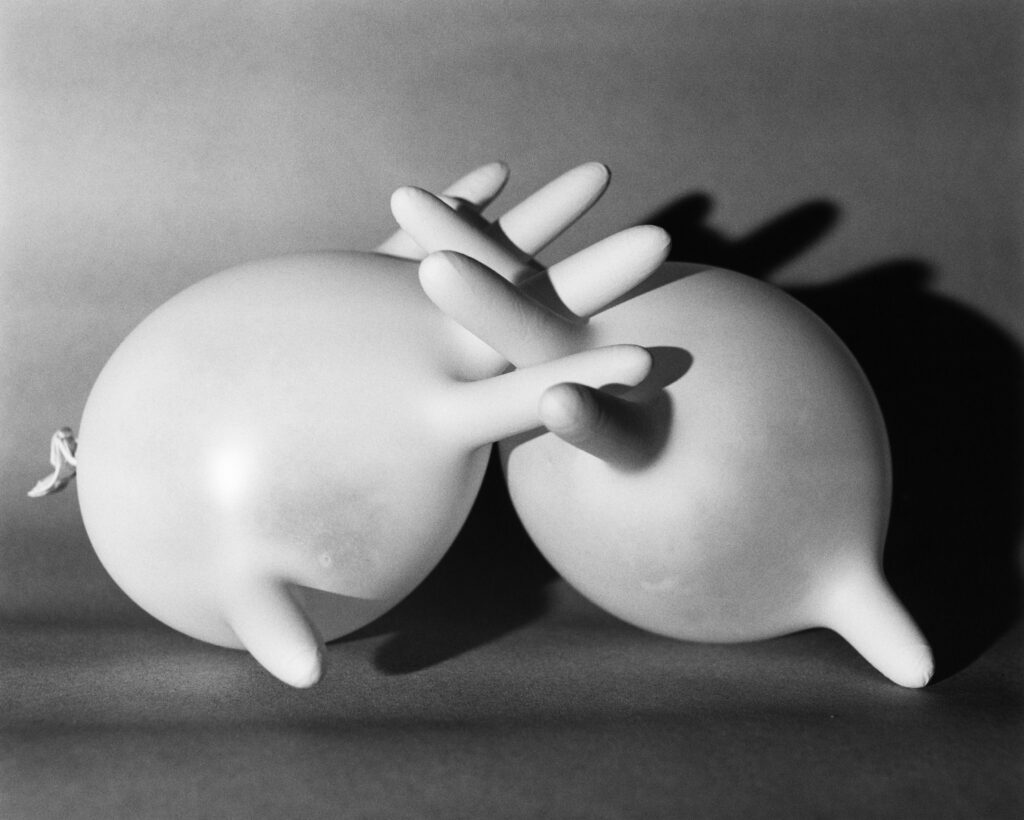

Your practice emphasizes intuition and chance, allowing situations to unfold rather than directing or staging photographic moments. How do intuition and restraint work together when deciding whether a moment becomes a photograph? You have spoken about resisting images that feel over-determined, where meaning is quickly resolved, in favor of photographs that leave space to dwell. How do you define restraint in a photograph, and what does that openness allow the viewer to experience?

I think you want to restrain yourself from being too obvious. You want to leave things open so that there is free will. Things can be implied in the pictures, but you can certainly over-imply them. Robert Adams uses the expression ‘inexplicable rightness’. So I think intuition begins when you don’t have that dialogue in your mind. You know, ‘Is this making sense? Is this not?’ It looks good, feels good to take the picture. With intuition too, there’s a lot of anticipation. You sense that something is brewing.

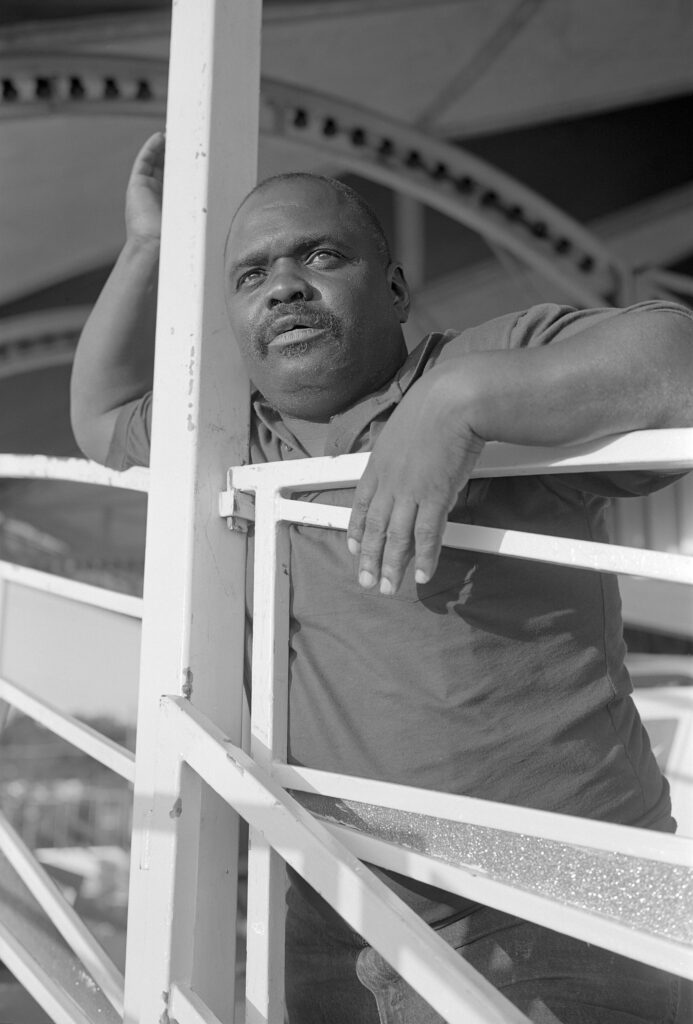

ATL Terminus and Greater Atlanta document the city through contrasting temporal conditions, the airport as a space of transit and the city and suburbs through long-term return. How do these two bodies of work speak to one another?

There are pictures of Atlanta taken from airplanes in ATL. To me, Atlanta is a modern city. It has some vestiges of the old South, but it is very corporate and very functional.

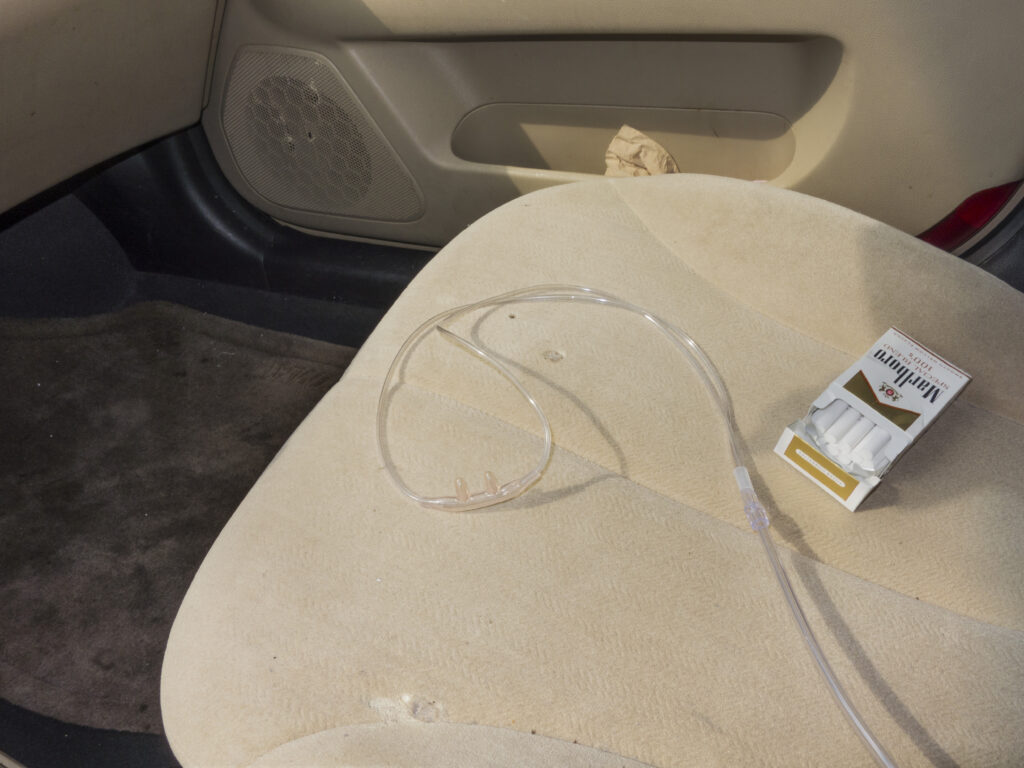

Greater Atlanta is about something else. It’s about fossil fuels, capitalism, and civilization. It’s about how things progress. There are pictures in Greater Atlanta that point toward prehistory, toward the land before development and before this modern system was put in place.

ATL is more about a state of limbo. It’s about traveling, about people moving between places. They have their suitcases. They’re passing through rather than being anchored. So the two projects are not completely yoked together. One looks at movement through the city, and the other looks at the deeper structures that shape what the city is.

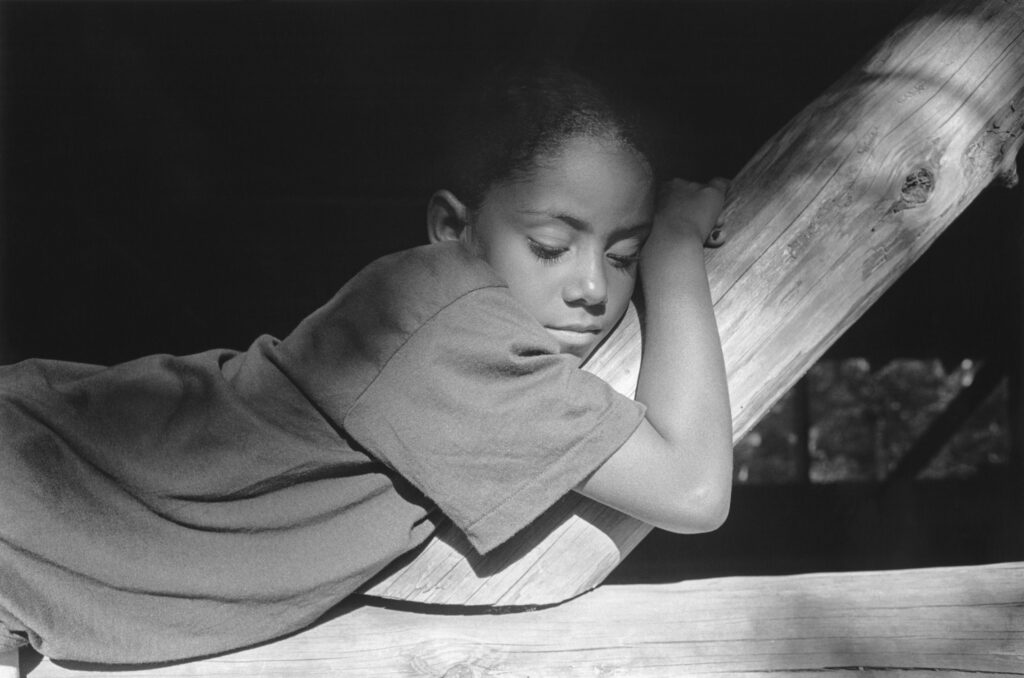

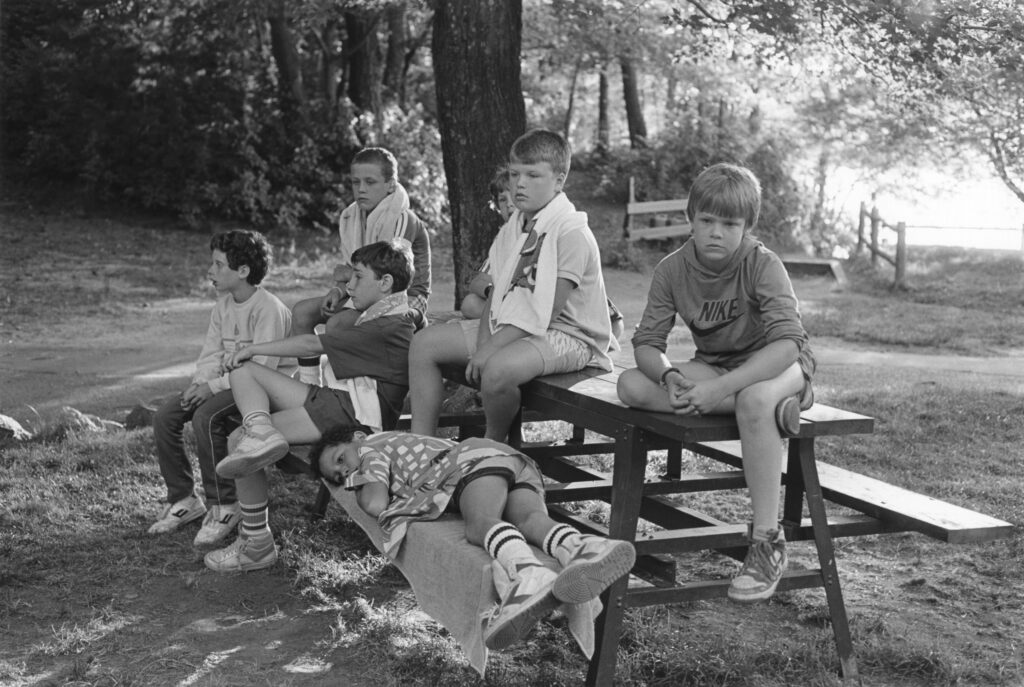

Developed over nearly two decades, Summer Camp documents daily life through routine, social structure, play, and solitude. Did the project gradually become less about individual moments and more about observation itself, about how time moves through people and relationships?

Summer Camp was done over a decade from the first picture to the last, maybe twelve years, and it only takes place during a couple of months in the summer, which makes it hard to get into. For a long time in America, kids went to camps like this: you had a campfire, a lake, a dining hall, cabins with screen doors. I tried to capture how no time was really passing, a twentieth-century experience. It’s a little like Lord of the Flies at times.

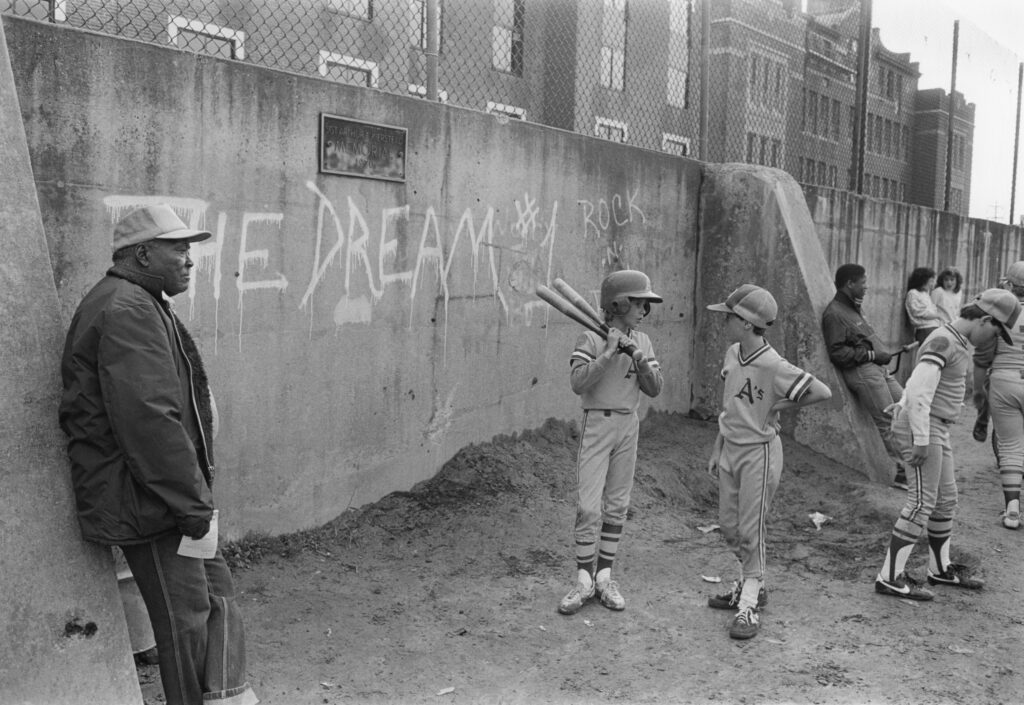

It connects to other bodies of work I’ve done. The Players was mostly boys, some girls, but it was about Little League baseball. That work, and Summer Camp, and even the carnival pictures, which are more teenagers, all share something: a strong setting. The baseball fields with chain-link fences, uniforms, gloves. The camp with its cabins and lake.

In all of them, the kids are more or less free of their parents. They have coaches or counselors, but they’re inside an intense activity. Baseball is about winning and losing. Camp isn’t about winning and losing, but it is about being together, about summer, about having a lot of time on your hands. In both cases I think I’m pretty much the same photographer. I’m different in something like the South Trilogy or ATL, but in these I feel very consistent.

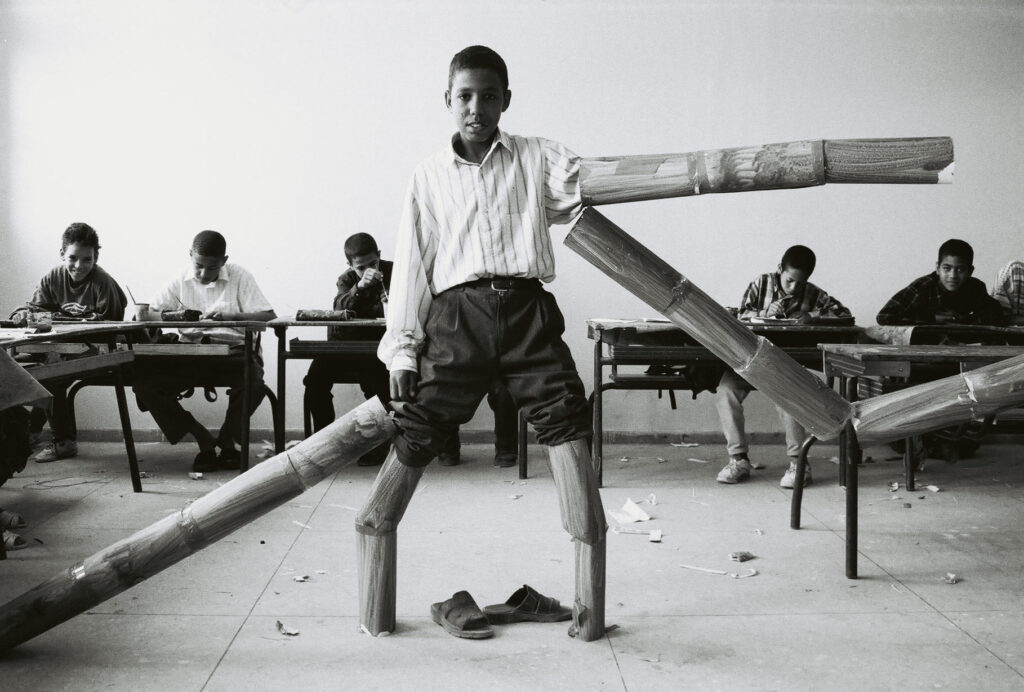

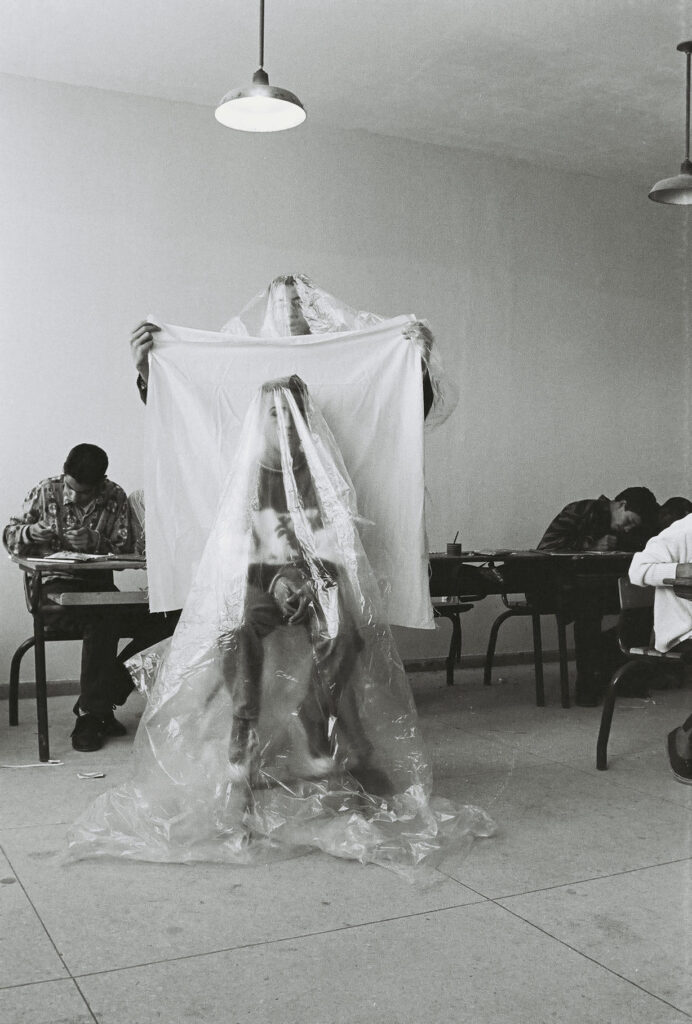

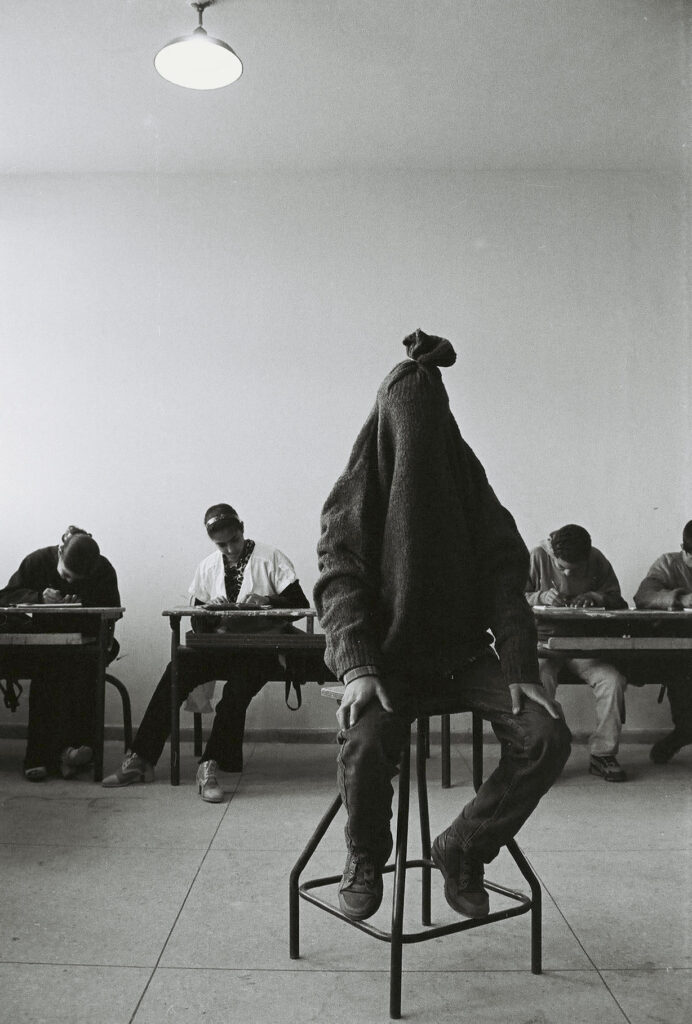

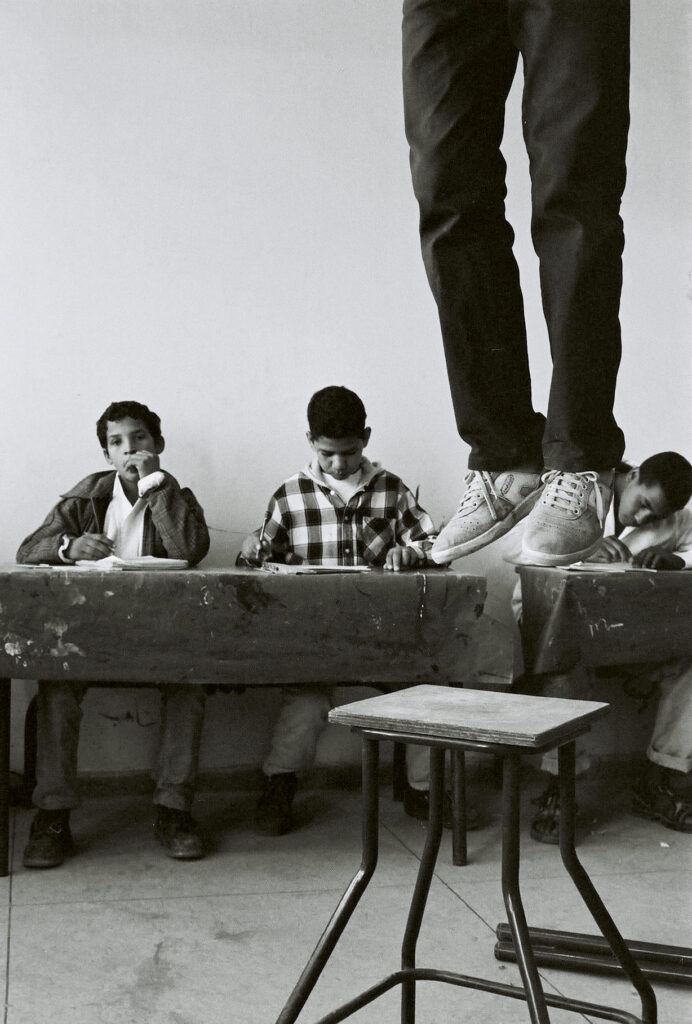

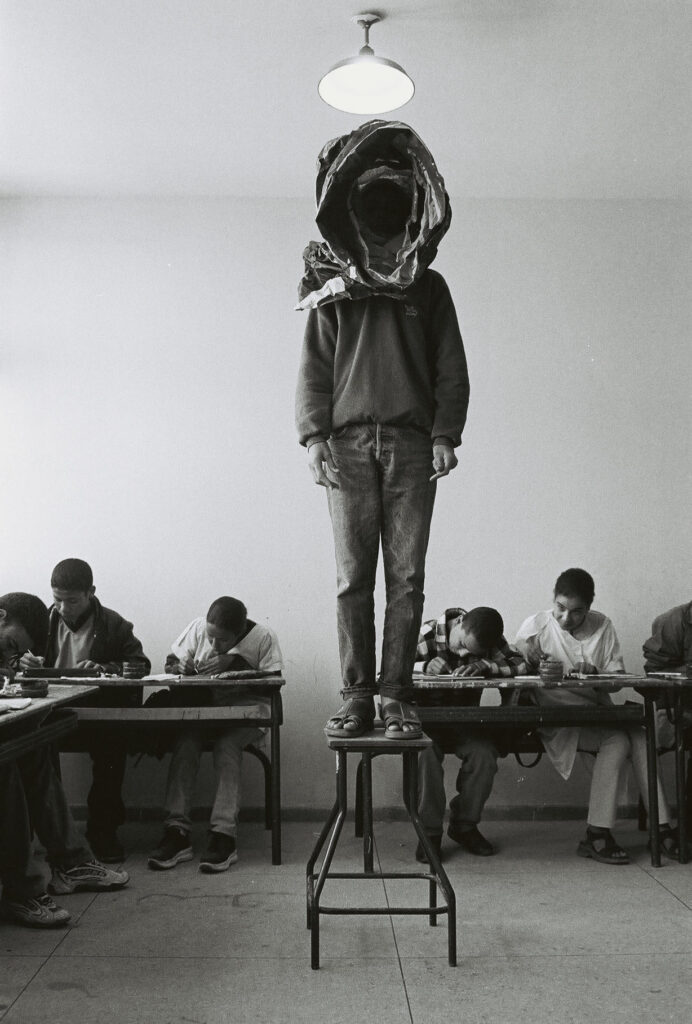

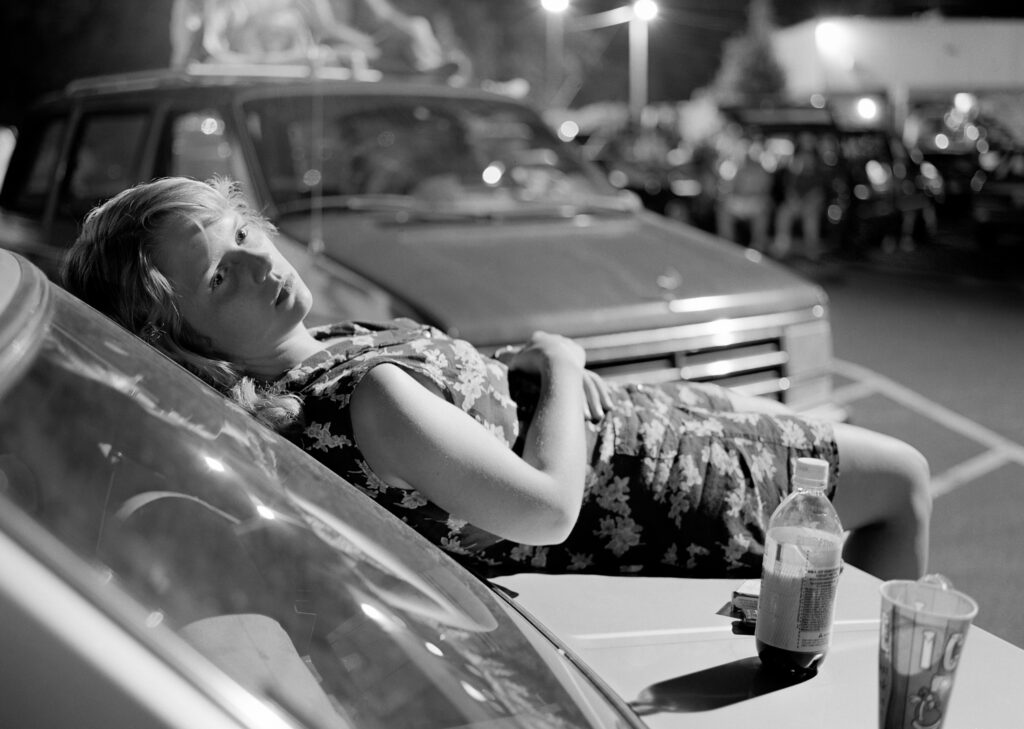

Kids and Teens focuses on children and adolescents in public and semi-public spaces, often at moments of pause or self-awareness. What draws you to these in-between states, and what do they reveal to you about looking, being looked at, and the act of noticing itself?

Physically, kids are interesting. Teenagers, their faces, their heads, and their stories are interesting. They carry this sense of prospect, of becoming an adult.

I did a lot of kids and teenagers work earlier on, when I was in my twenties and thirties and childhood was closer to me. Cartier-Bresson and Helen Levitt did great work with kids early on too. You also had more permission photographing kids than adults then. They were less self-conscious.

Later I photographed younger people in their twenties. As I grew older, my subjects grew older too. Now I photograph anything. I have a daughter who’s eight, so I photograph her a lot.

I think I did a certain kind of work that belonged to a time before. That life isn’t the same now. There isn’t the same relationship to time. There was more boredom, more waiting. You had to rely on your own resources more than you do now, when you can just turn something on and be stimulated by someone else’s production.

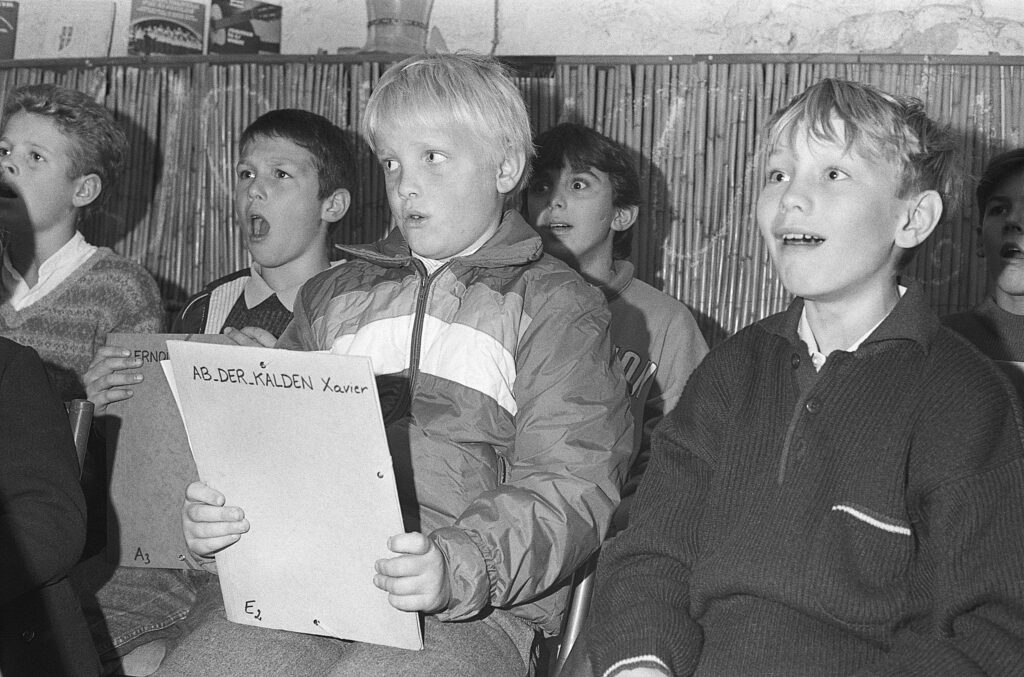

France 1987 presents photographs made in public spaces and revisited decades later. Looking at this work now, what does it reveal to you about changes in public life, physical presence, and social interaction?

It really seems like a timepiece. It seems connected more to the world that Cartier-Bresson and Doisneau and Atget photographed. It’s looking like a different time. That’s a big shock to me.

France preserved a more traditional way of dressing for longer. In America there were more gaudy T-shirts with sports teams, more sportswear. In France people kept wearing traditional clothes without insignia.

Now that’s changed. There’s more writing on people’s clothes, but it seems like an earlier time: End of a period when the present was still in touch with the twentieth century. That really gave way in the 1990s.

Your archives often sit for years before being edited or published. How does distance affect what you choose to keep, print, or release?

Time is interesting. I took the pictures then, but when I’m editing now, it feels like the work now. You have more detachment the longer you wait. You might have all these ideas in your head about what you’re doing, then years later you just look at how they work for you now. There’s this partnership between me and my present self and me and these former selves that don’t exist anymore.

You have worked almost exclusively with film and printed by hand. How does that process shape your way of seeing?

I first photographed a lot of six-by-nine centimetres. I still use 35mm as well. I was photographing this morning, actually, traffic and circulation, bicyclists and scooters, in fairly dark conditions. But in something like South Central, pretty much every picture is medium format, six-by-nine. Some are a mix, but most of them are.

I like darkroom prints. I like silver on paper. I like the process of working. I’m in Paris now and I don’t have a darkroom here, and the weather is pretty lousy. It would be great to go in and print instead of trying to make pictures in bad light, although there’s something interesting about that too, because I’m used to working in nicer, warmer light.

I use digital sometimes, mainly for commercial or fashion work if they want color. But for me film is better at capturing atmosphere, especially backlighting. I love backlighting, and I love when there’s moisture in the air. Digital tends to remove what’s in the atmosphere. It becomes hyper-clean. It creates light where there isn’t any, and I don’t really see the point of that.

A lot of people photograph in low light digitally and the pictures come out, but it doesn’t look right to me. Digital embellishes things. I take a lot of iPhone pictures too, but I’m more moved by a new Robert Frank picture or a new Winogrand picture. If there’s a new Eggleston picture, that can hit me too

Across your career, photography appears as a sustained practice of attention. What keeps that practice alive for you now?

Everything is up in the air because of the situation in the world. I’m in Paris. I have French citizenship. My mother was French. My daughter has French citizenship. My wife doesn’t. Our house and darkroom are in the States, so it’s America, France, Paris, somewhere else, I don’t know.

I drop my daughter at school every morning, and there’s this area, Porte de Chambert, with a lot of traffic, a rush hour, bicyclists of all kinds, people on scooters, people pushing strollers, all these different kinds of vehicles colliding. I started photographing there, which I wouldn’t have thought of a couple of months ago.

The solstice light is very dim. There are headlights now, which weren’t there a few days ago. I’ve also been photographing at La Plastique, an area with a metro stop, a cinema, a big school, a few cafes, where all kinds of people meet. People smoke outside the metro before they go in. That’s a lot of the street photography I’ve been doing.

I look at photographers like Robert Adams now, in his eighties, still putting out books from the past twenty years, and they feel very alive and very wise. Maybe they’re not for everyone, but I see a really interesting photographic mind at work, someone whose pictures are dense with a lifetime of experience.

I wonder if I’ll have that. I have an eight-year-old daughter, I feel fine, I still have good reflexes. I don’t know the future yet.