“It is in the nature of the mind to make something out of nothing, so an empty state allows the mind to rest and opens doors at the same time.”

It might have taken Chantal Elisabeth Ariëns ages to pull herself out of the state of chaos and into the utopia of emptiness, but such a transition defines what she produces today, from photographs to prints. Relieving certain emotions to provoke certain memories ushers the multidisciplinary artist into conjuring her most reflective essence, giving a home to the works of art she treasures the most.

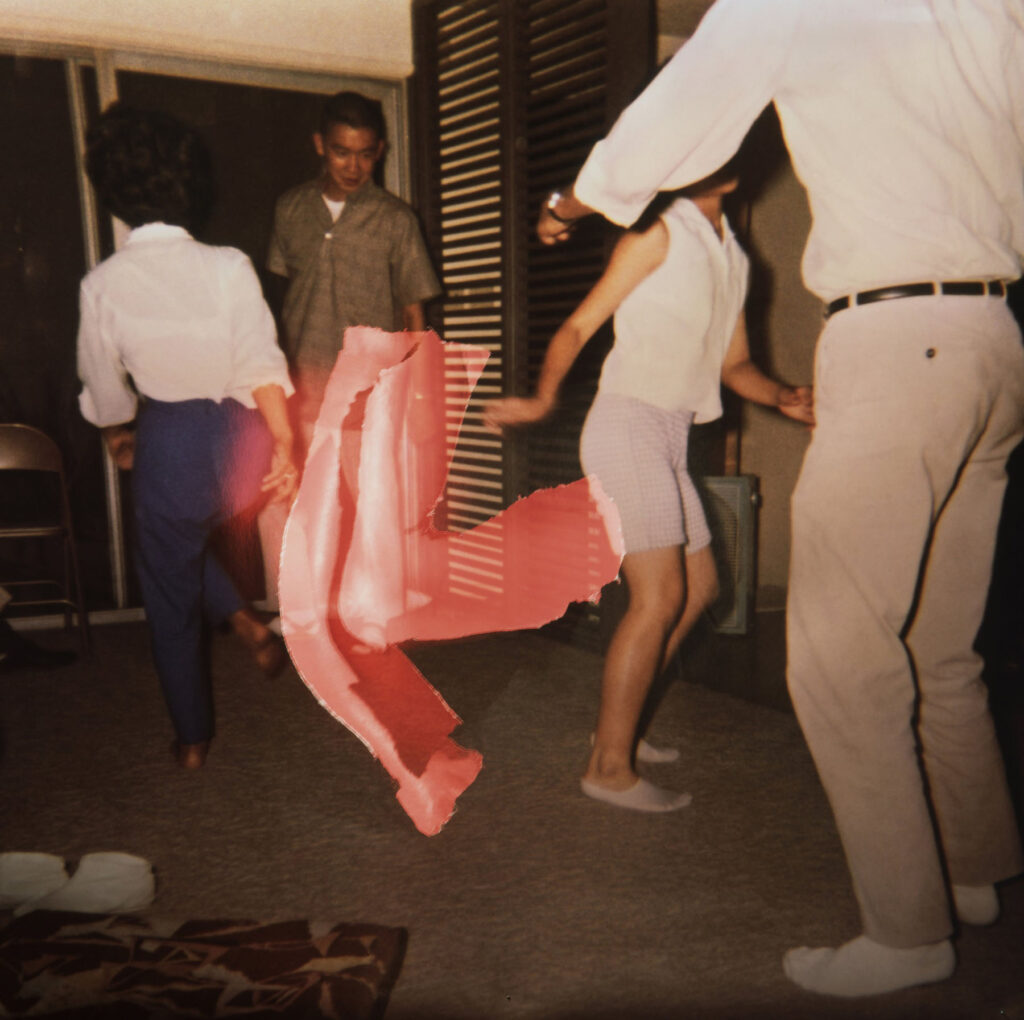

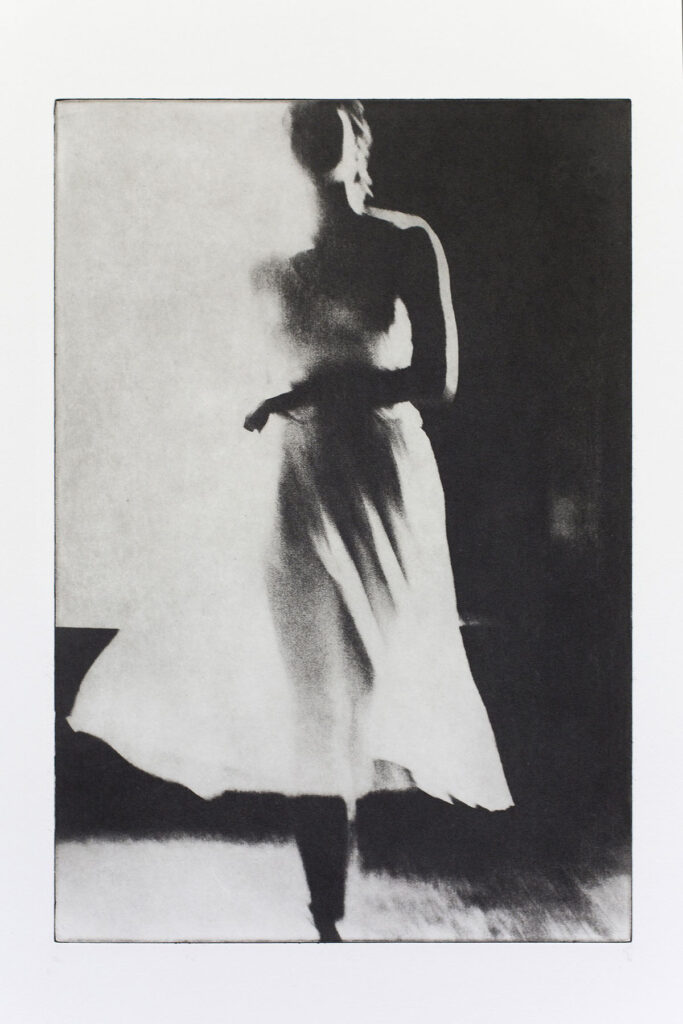

From her reverence for water as a distilling element of life to the reminiscence of her sister’s youthful time, Ariens personifies the glory of existence: the stillness in dancing, the melancholy in capturing the relics of a passing, the times when realizations ask her to carry on.

I would love to learn more about your career transition. You first worked as a dancer, having studied at a ballet academy in Tilburg. You also modeled and assisted photographers. Why did you switch to photography? When did you realize it was time for you to hold the camera yourself?

I grew up with classical ballet and studied at the ballet academy, so my whole life was surrounded by ballet. But

“my dream to dance in a company like the NYC ballet fell apart.”

I started to look for something that could replace my passion for ballet. This was the quest. For a period, I started working as a model, where I got inspired by photographers I worked with and started to assist some photographers.

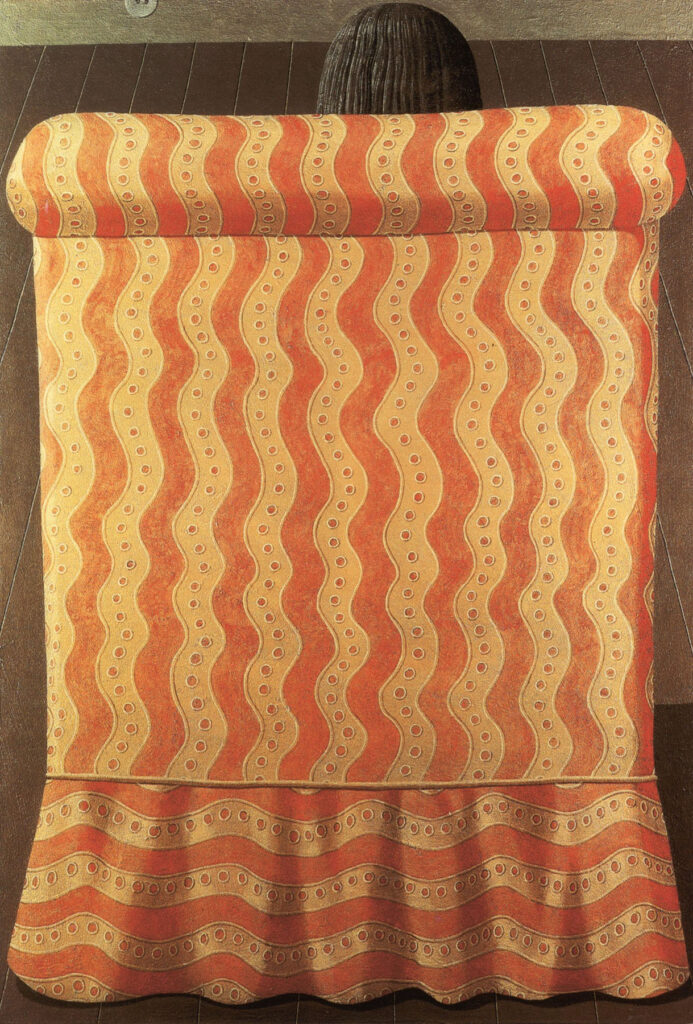

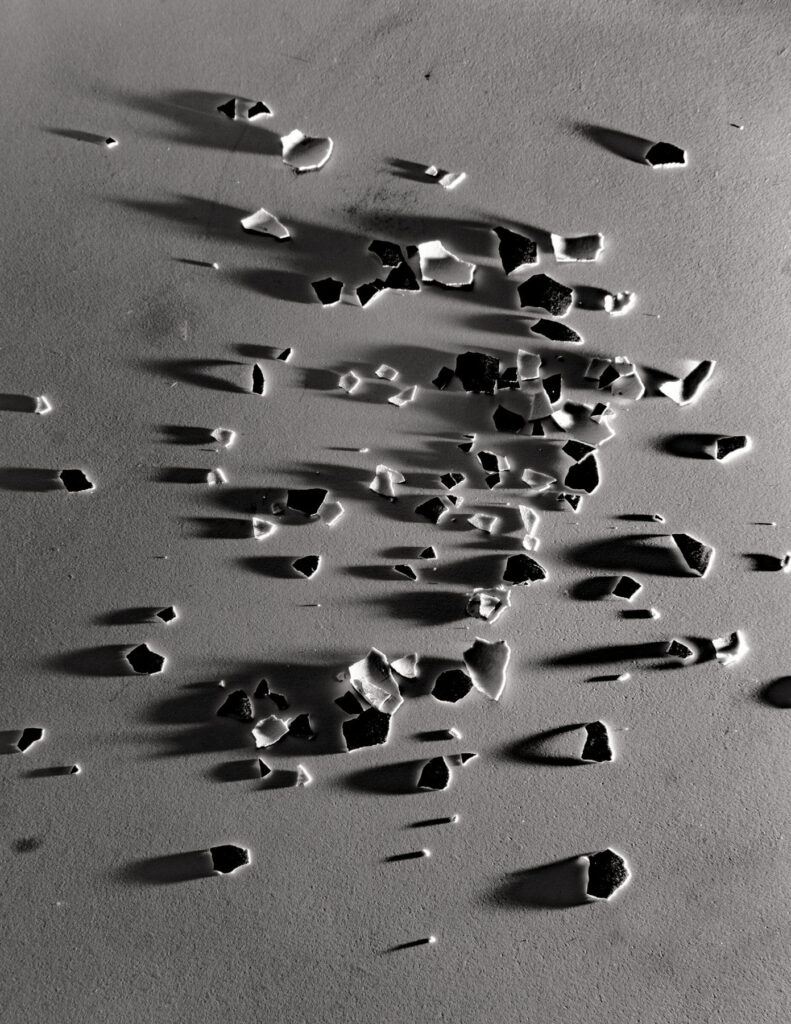

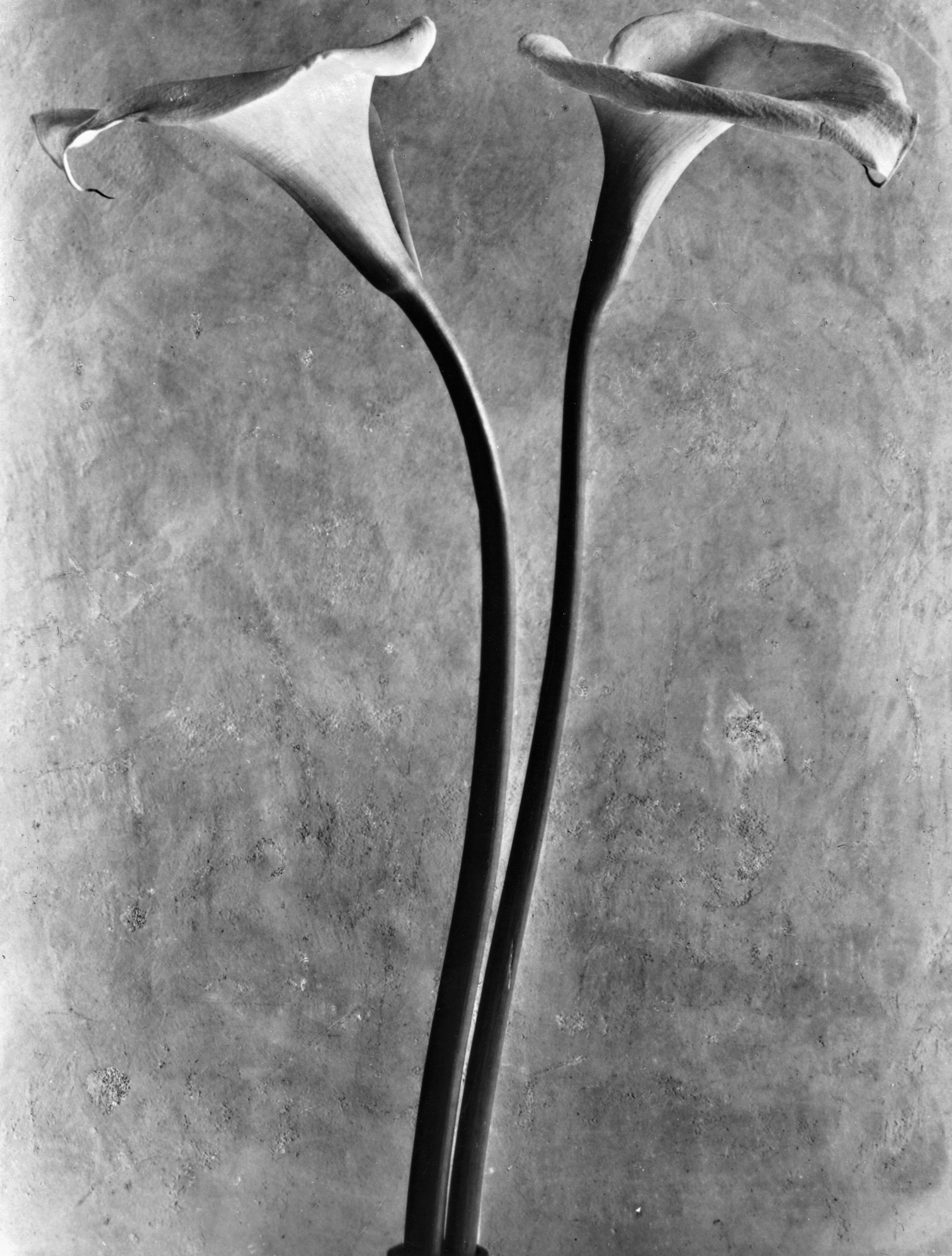

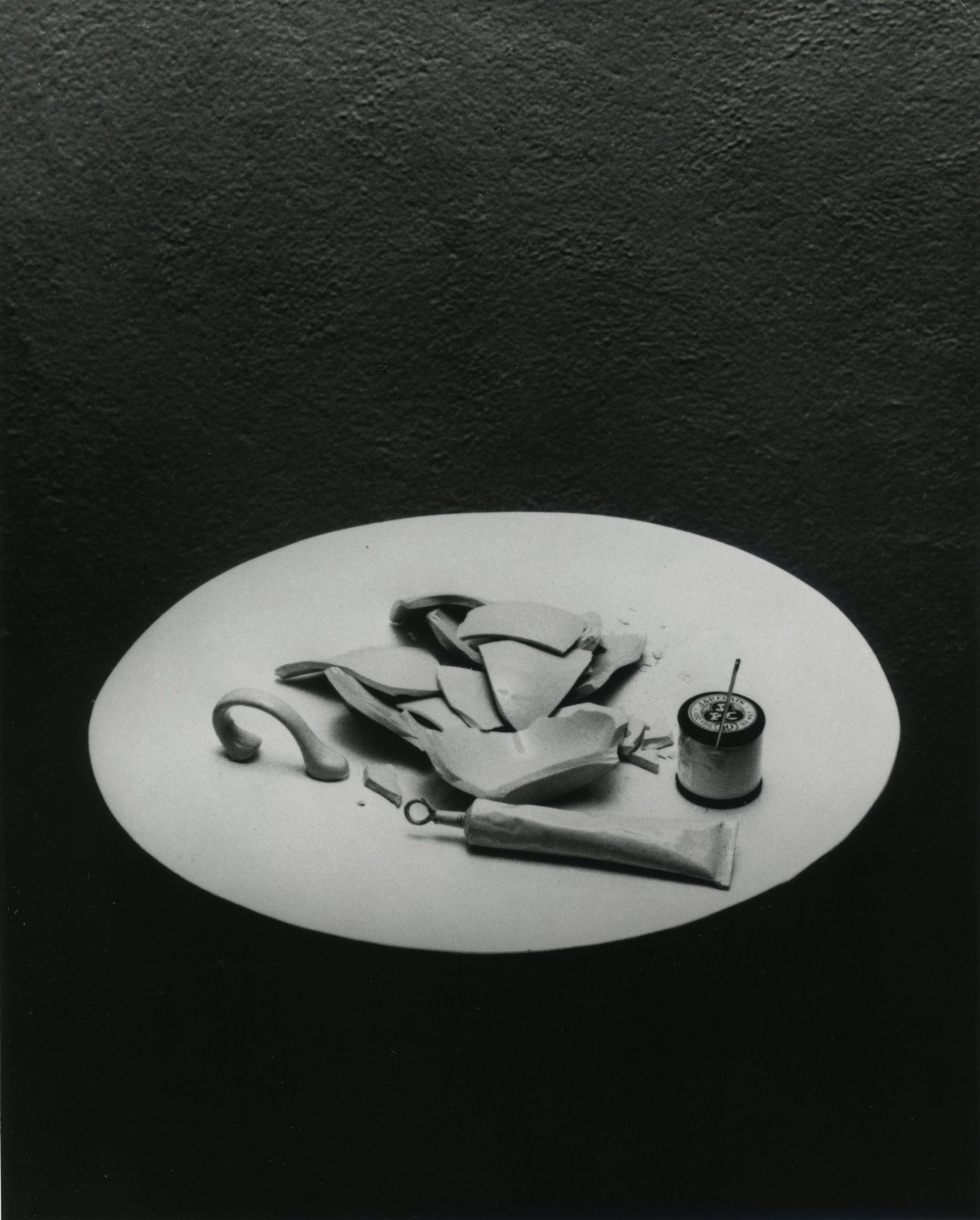

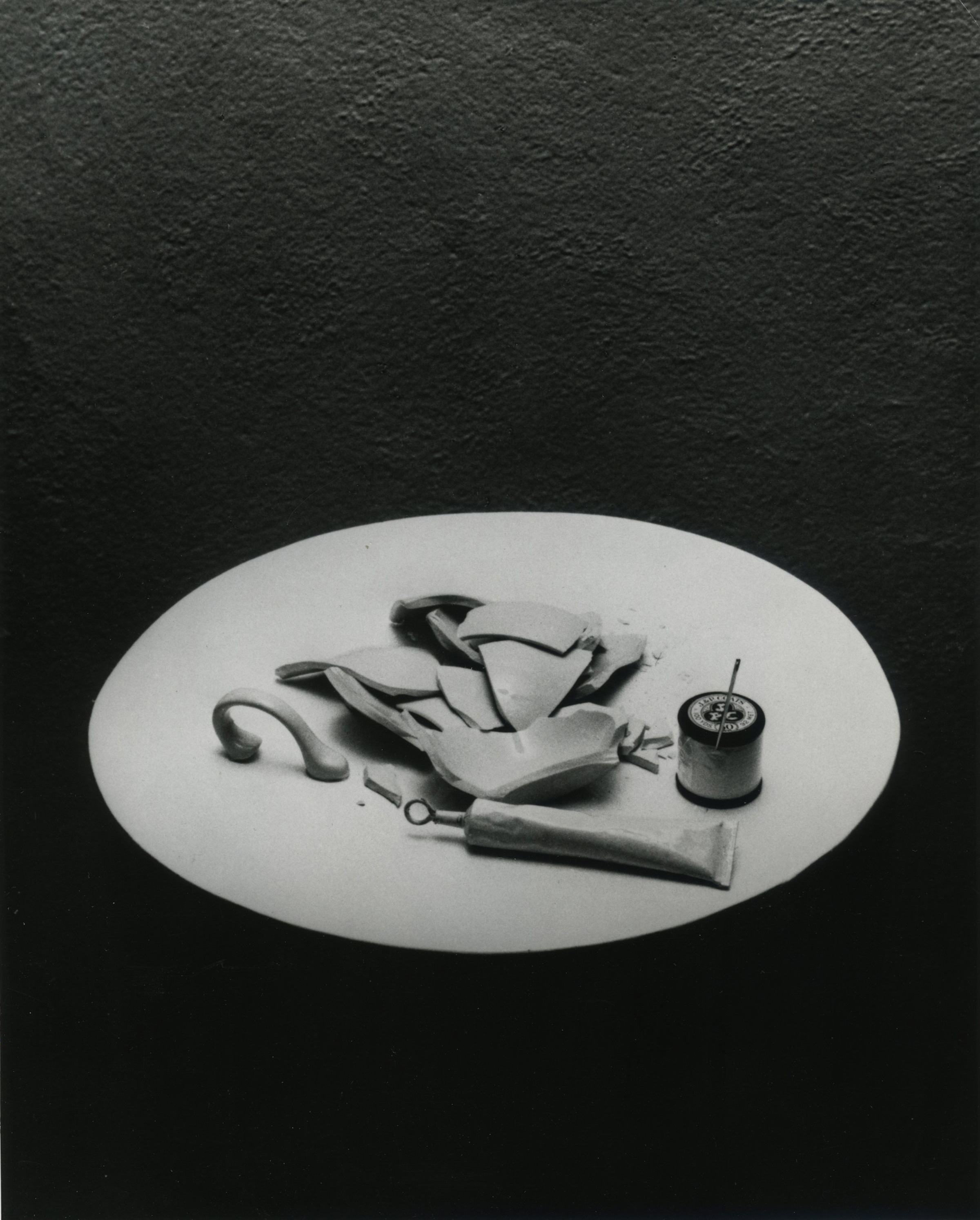

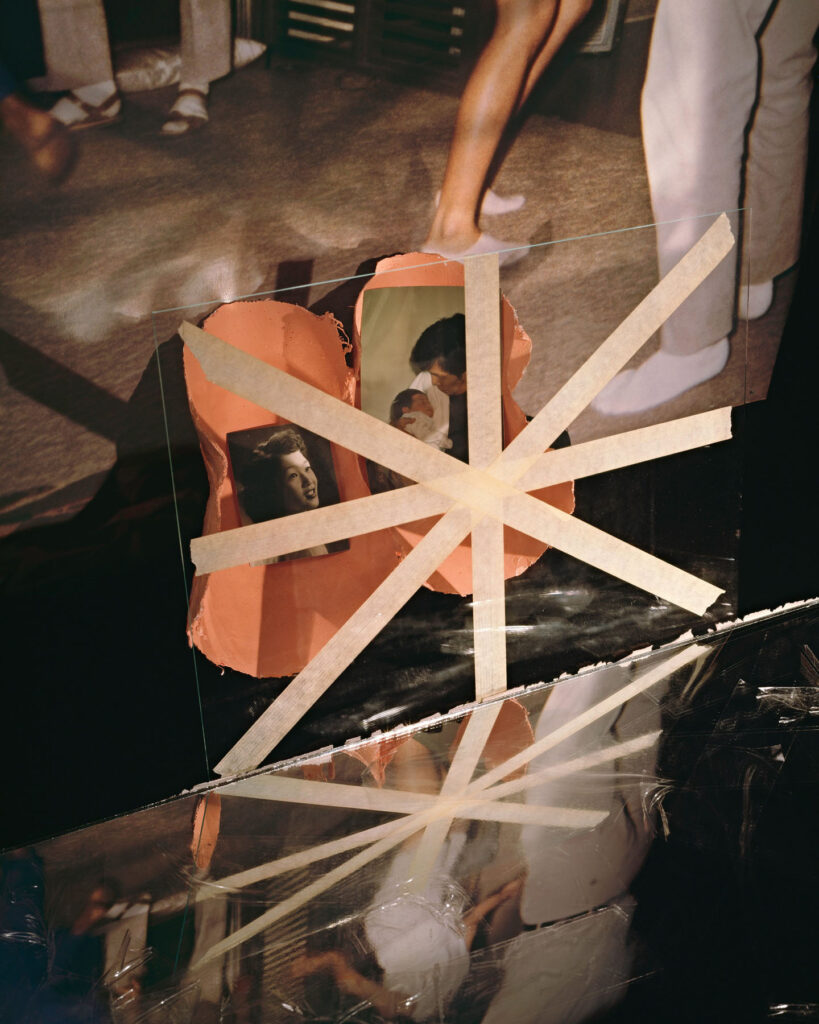

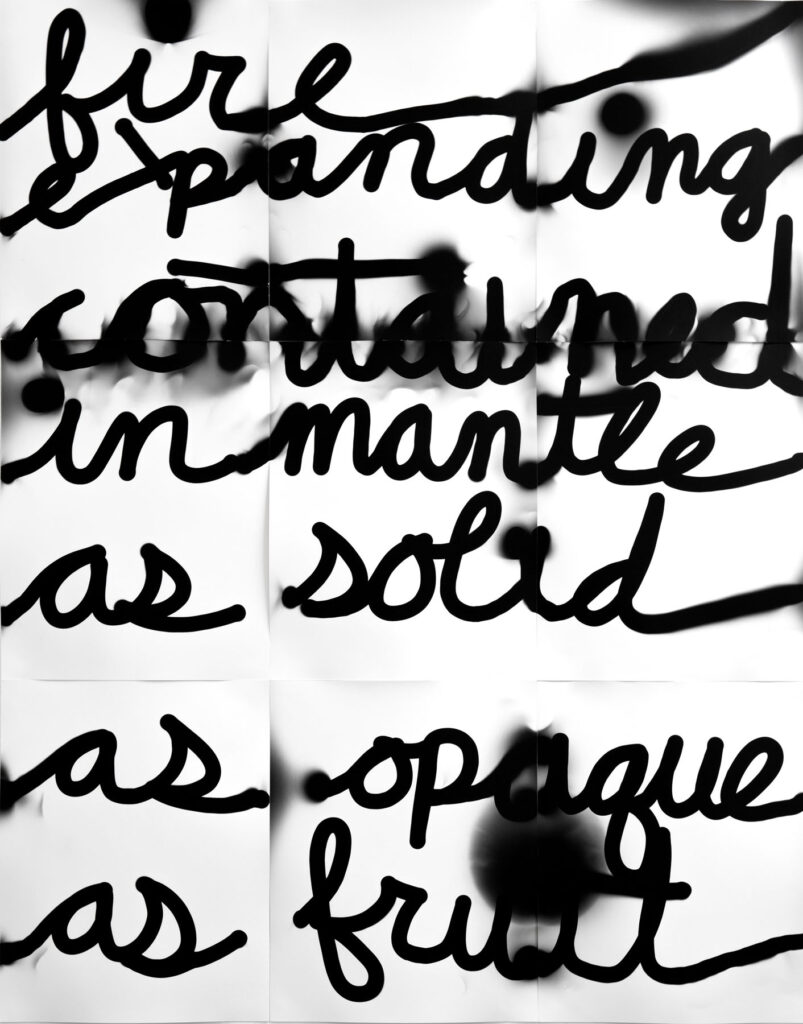

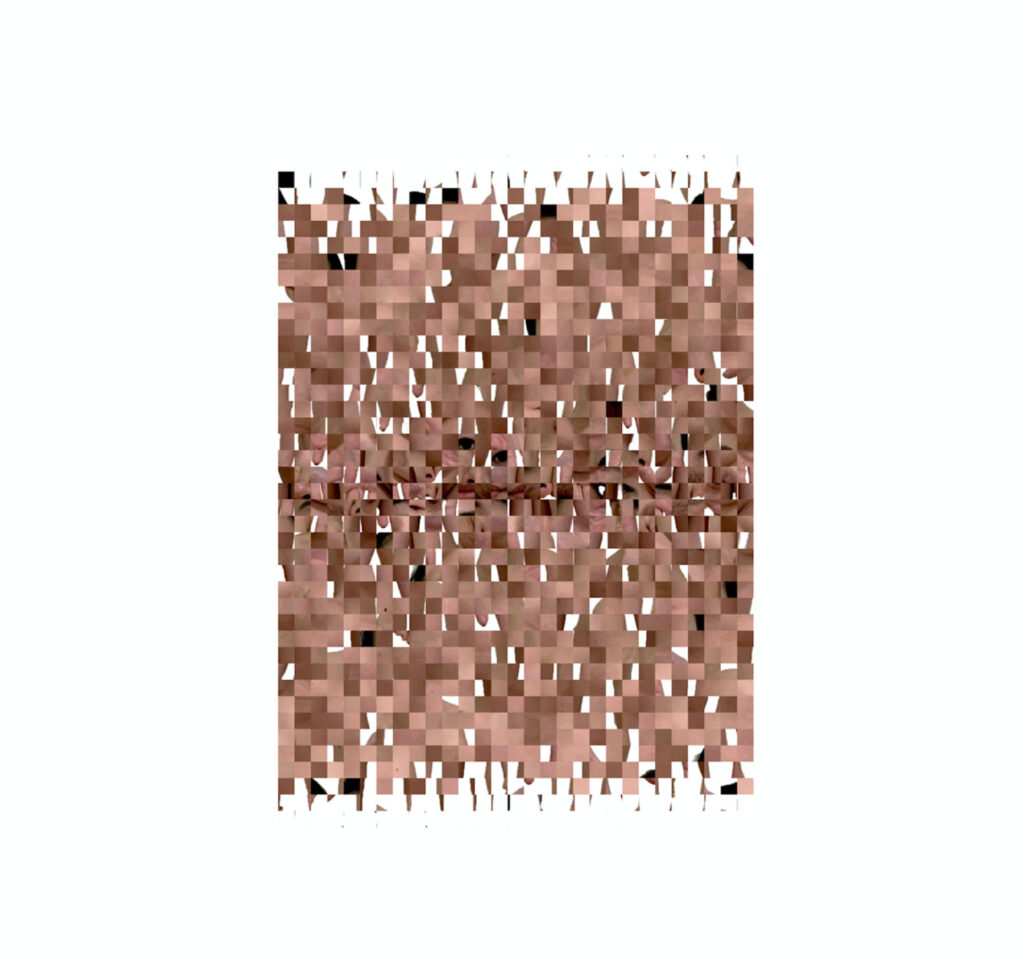

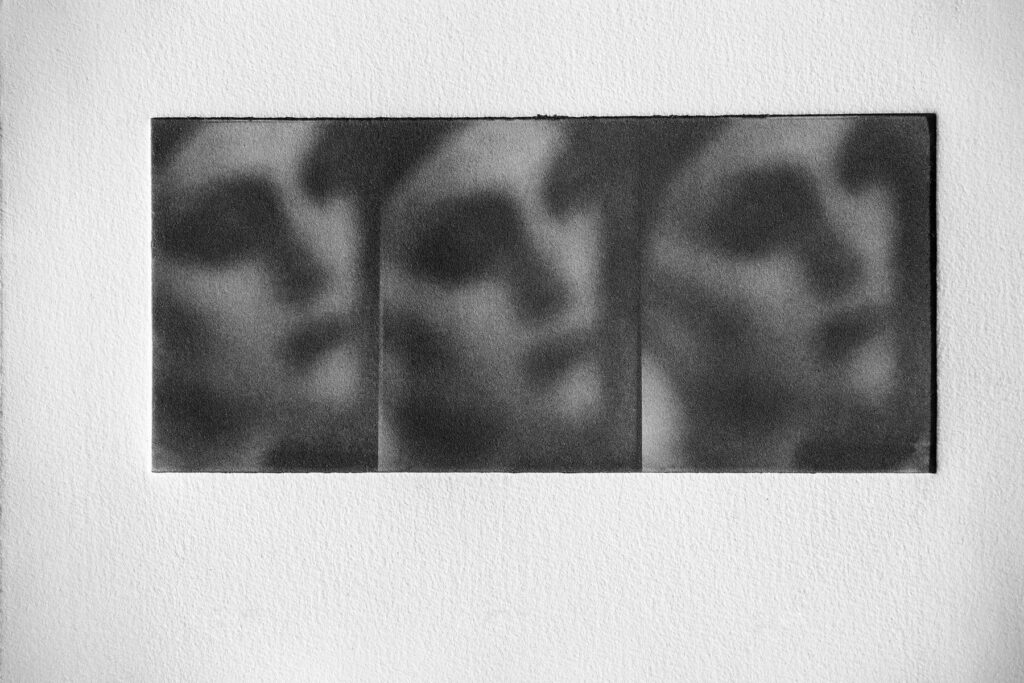

I am also a print-maker. I felt the need to create with my own hands, to give my prints more depth. I went in search of a craft technique that would allow me to do so, and this led me to the photopolymer etching technique. I love the tactility, the structure, the scent, and countless shades of black. The work itself is very intense and slow; it brings me to a more quiet part of myself and makes me more aware of how gratifying craftsmanship can be.

Delving deeper into your photographic philosophy, how did your ballet, photo modeling, and assisting experiences help shape your photography? What nuances from these backgrounds do you use in your practice today?

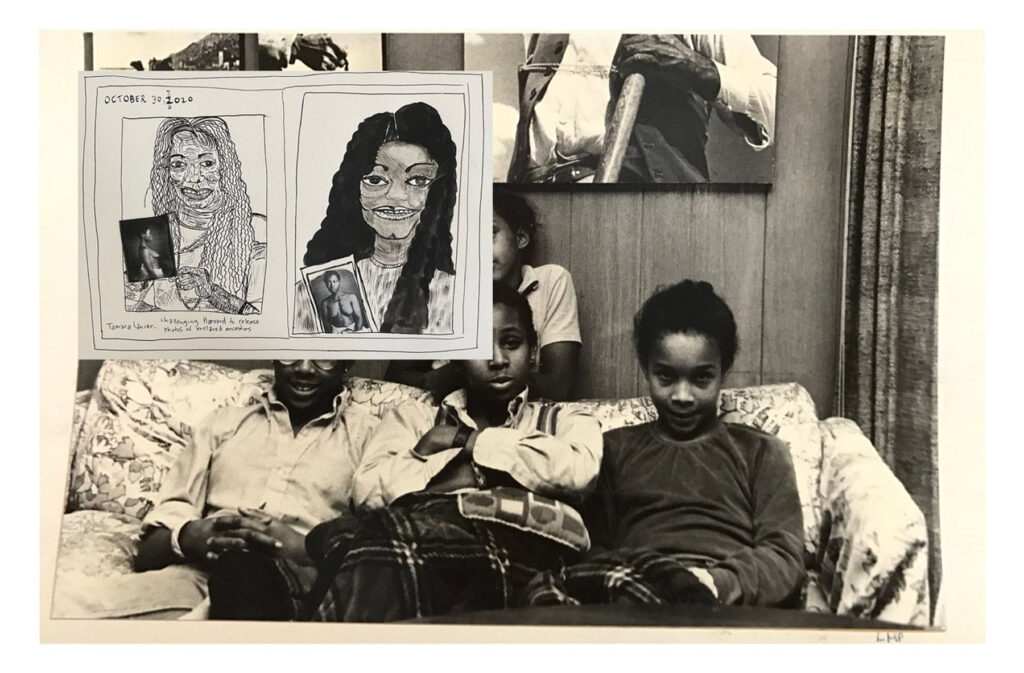

Dancing had been a way to express myself since a very young age. This was replaced by my love for photography. My father was a gifted photographer and a photo teacher in addition to his day job. He taught my sister and me how to print our own photos.

“Working as a model became the second part of my photographic education.”

It was wonderful to be able to learn from so many photographers, through their own ways of creating images, especially in the fashion world. Then, my process became different after working for magazines.

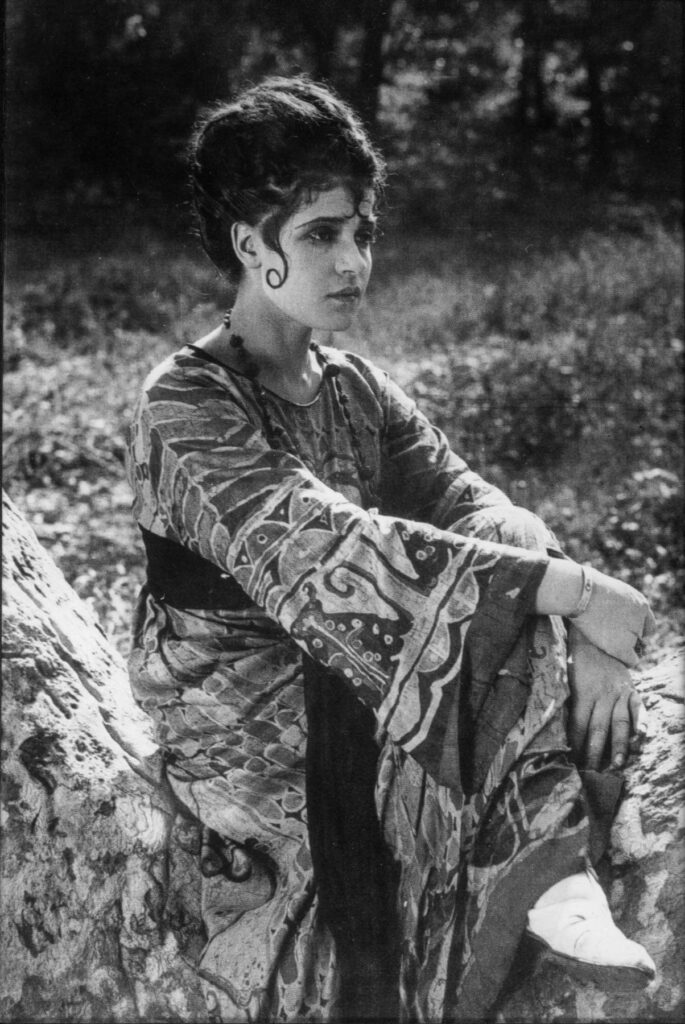

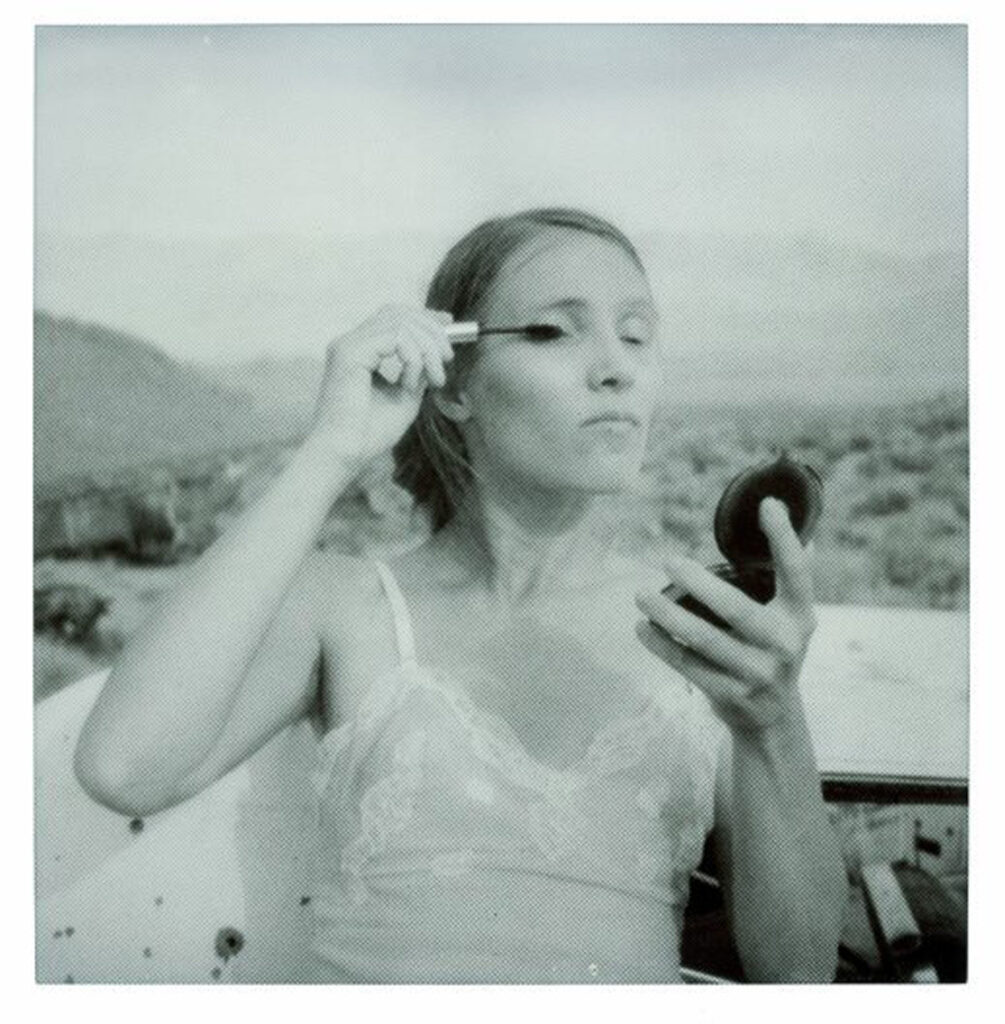

I felt the need to create from within after my younger sister passed away. I had to let go of concepts or themes to find out where my journey would take me. Gradually, I realized how everything turned out to be personal, including my relationship with the models I work with. I like to create an intimate atmosphere for the models to make them feel comfortable and be themselves.

I prefer to work with models with a background in dancing as they often move freely. It is important for me to make real contact in order to create images that move. They become personal from the moment I started to create my own world from the inside.

The inspiration of your works stems from the subconscious, a state of emptiness. How do you perceive an empty state? Is it meant to be filled, or just be left their void?

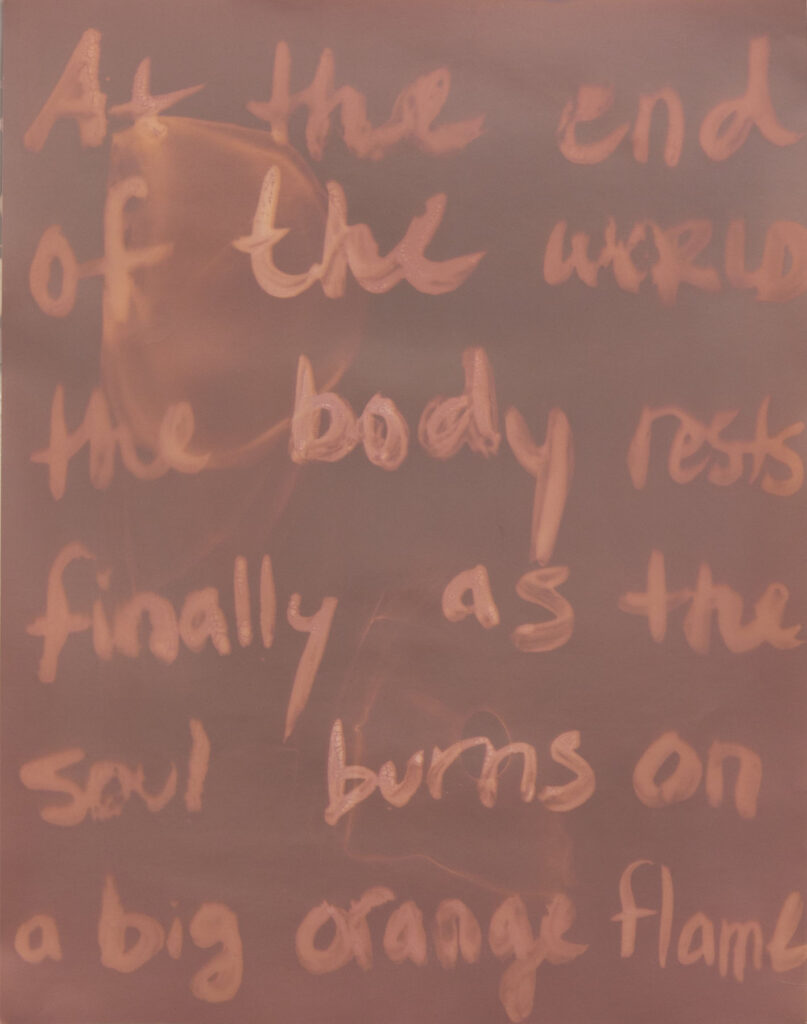

In the past, it was not easy to enter an empty state of mind overnight. It took me years to be able to let go, meditate, and practice. It is in the nature of the mind to make something out of nothing, so an empty state allows the mind to rest and opens doors at the same time. This is where it became possible for me to dig deep and create my personal work, by letting it be void with all that will come up in a natural way.

As you have written: these images arise by giving space to emotion and exploring where the connection lies between emotion and memory. Emotions and memories are stored in the subconscious. For you, what is the connection between emotion and memory? What kinds of emotions and memories do you want to evoke?

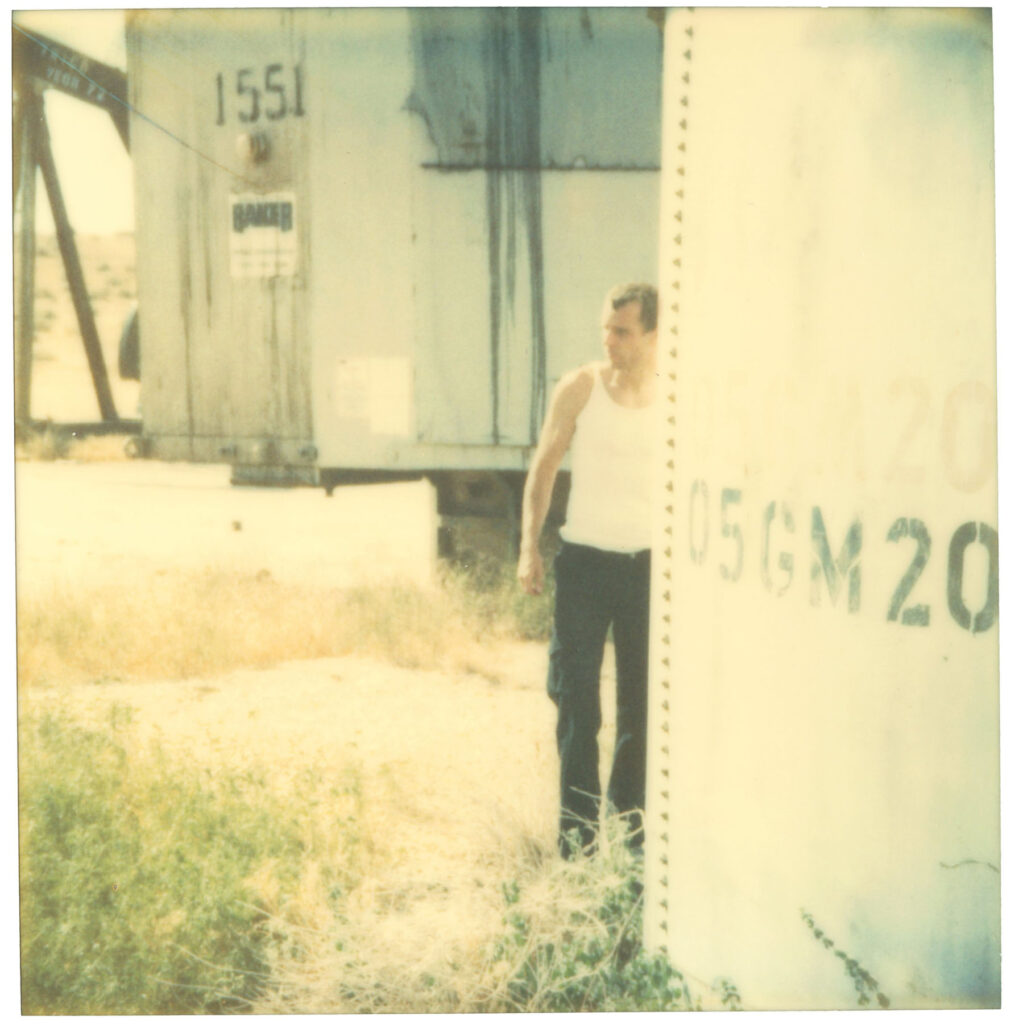

For me, memories come with certain emotions, so bringing up certain memories can evoke certain emotions. I try not to evoke these emotions as I prefer them to arise in a natural way. It is by giving space that they will find their way. For me, photography is about connecting to the landscape, the people, and myself. It is about creating my own world.

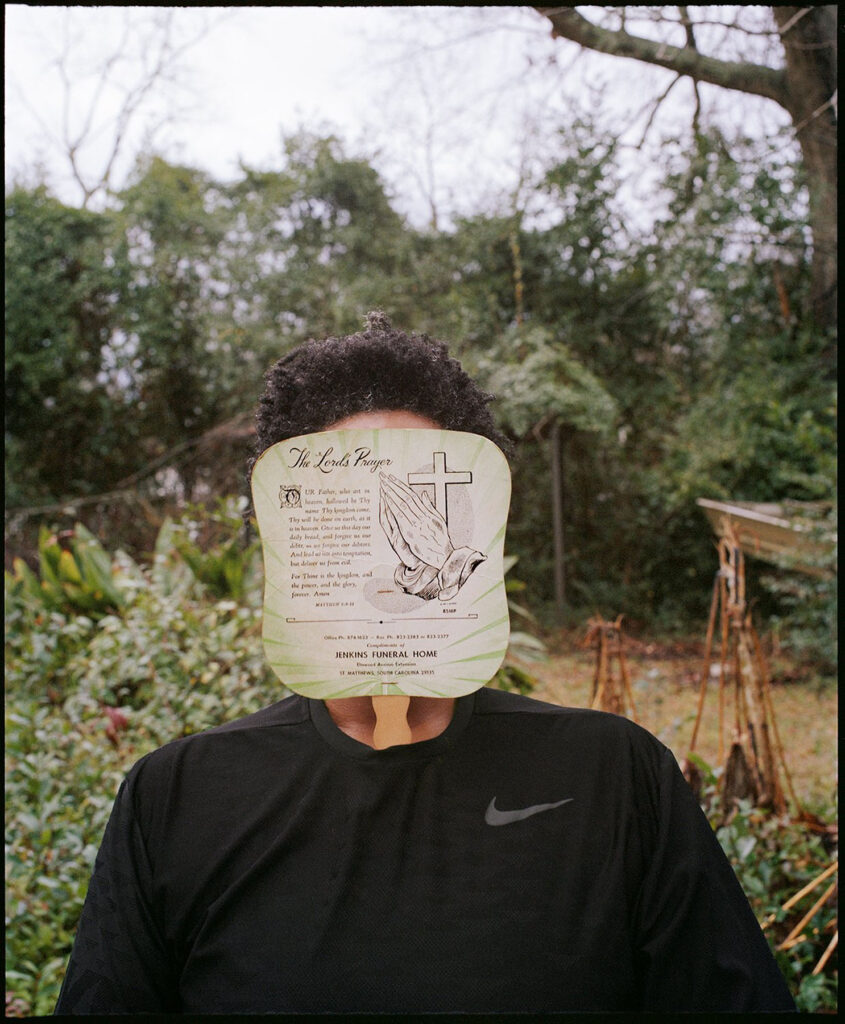

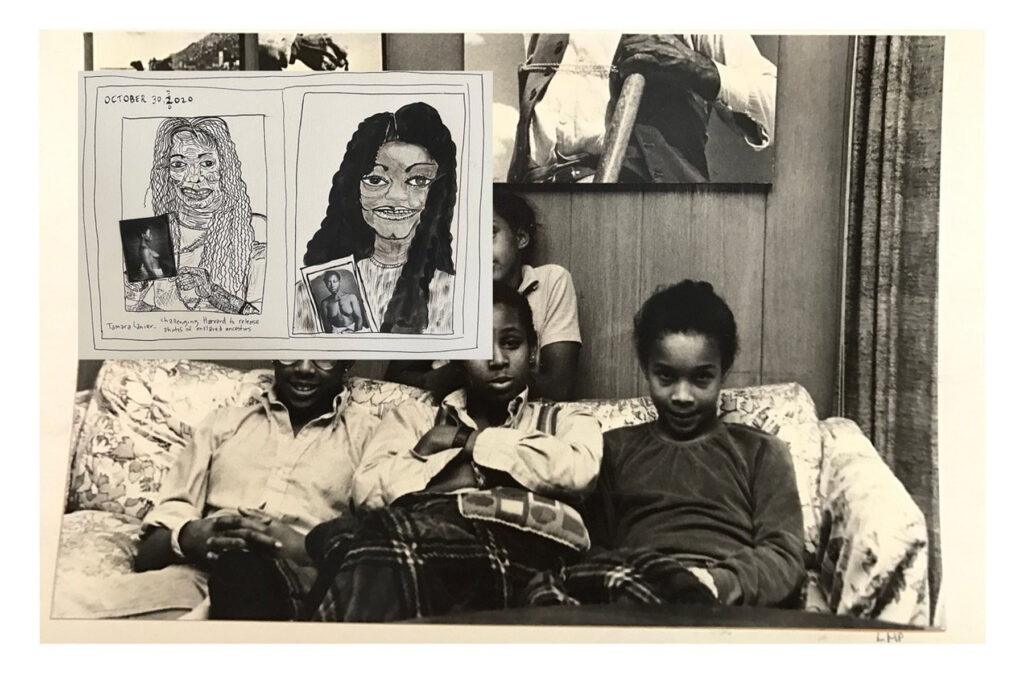

Let us go through a few of your works. Where Are You reminisces about your younger sister, a time when you saw her everywhere. Would it be all right if you guide us through your state in this series?

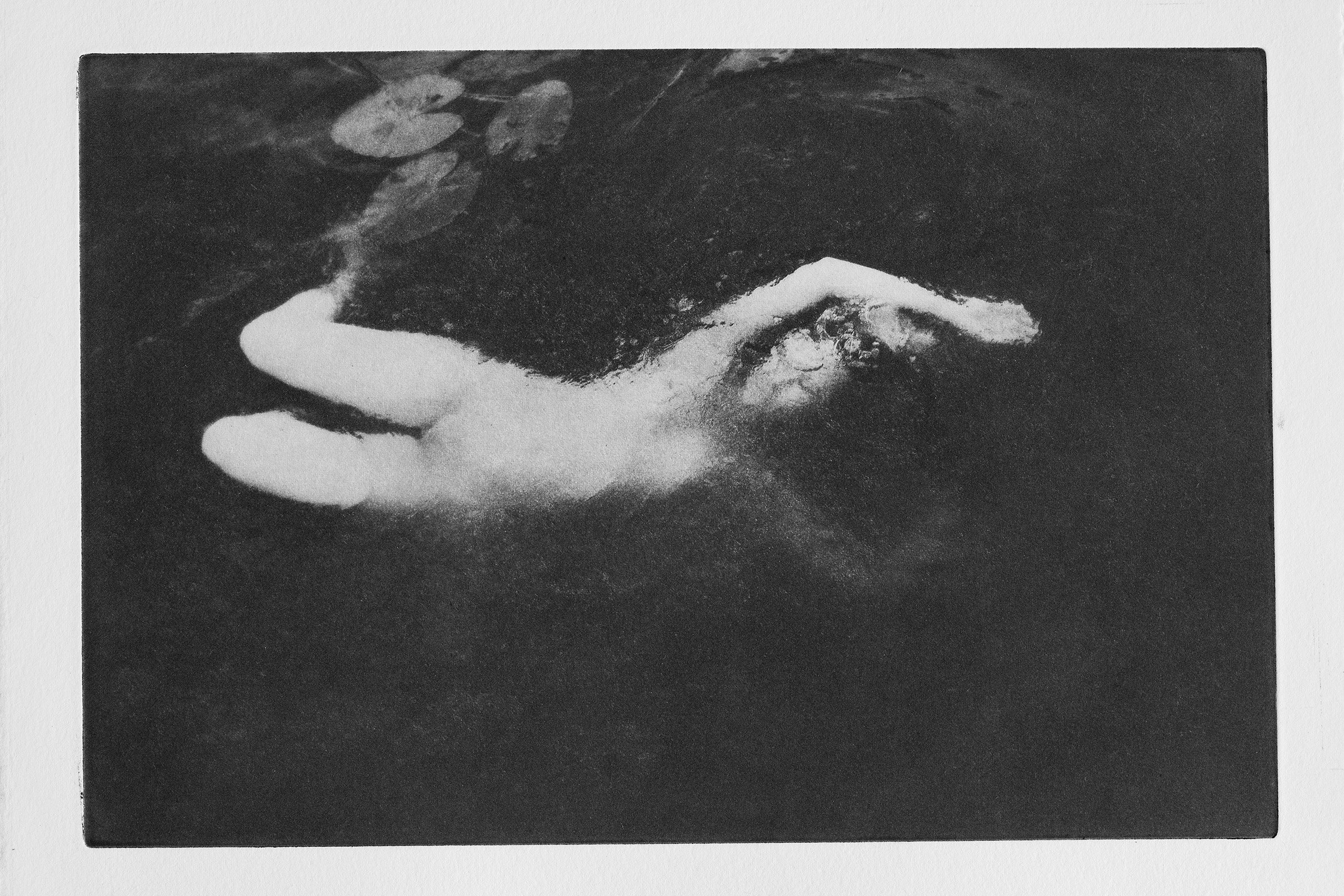

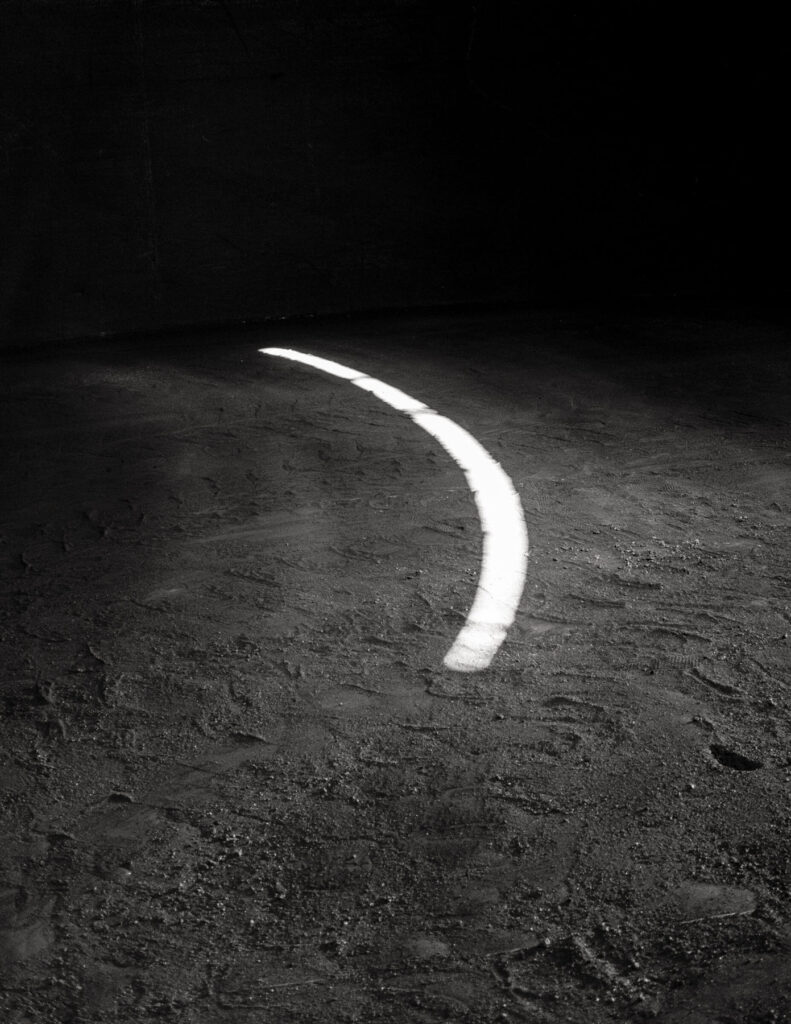

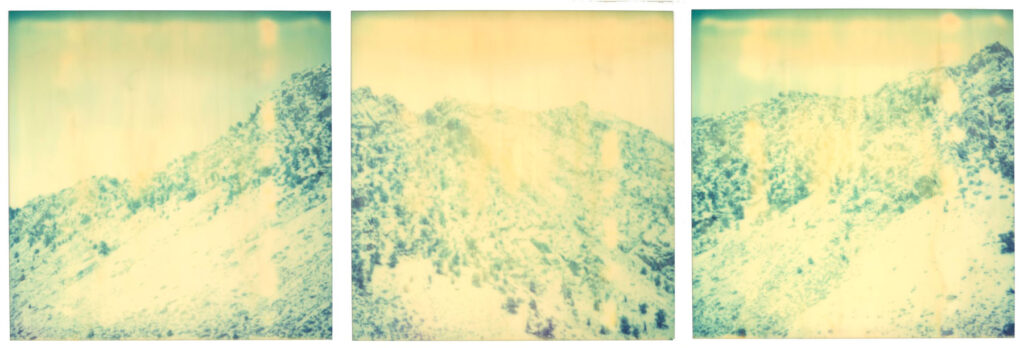

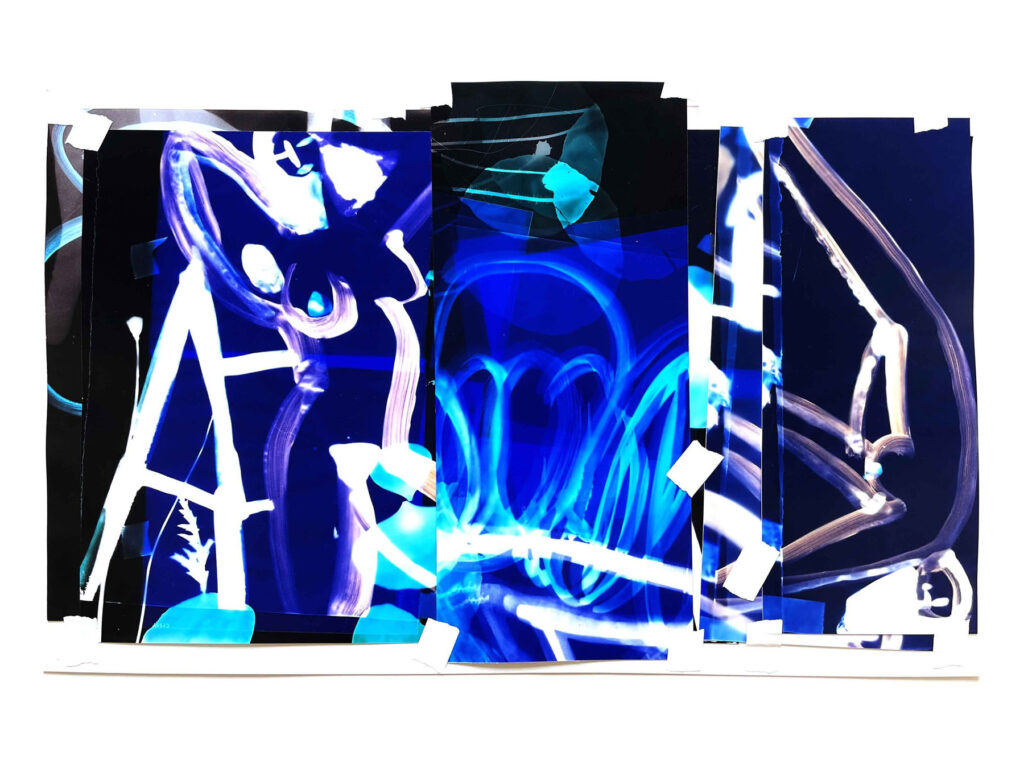

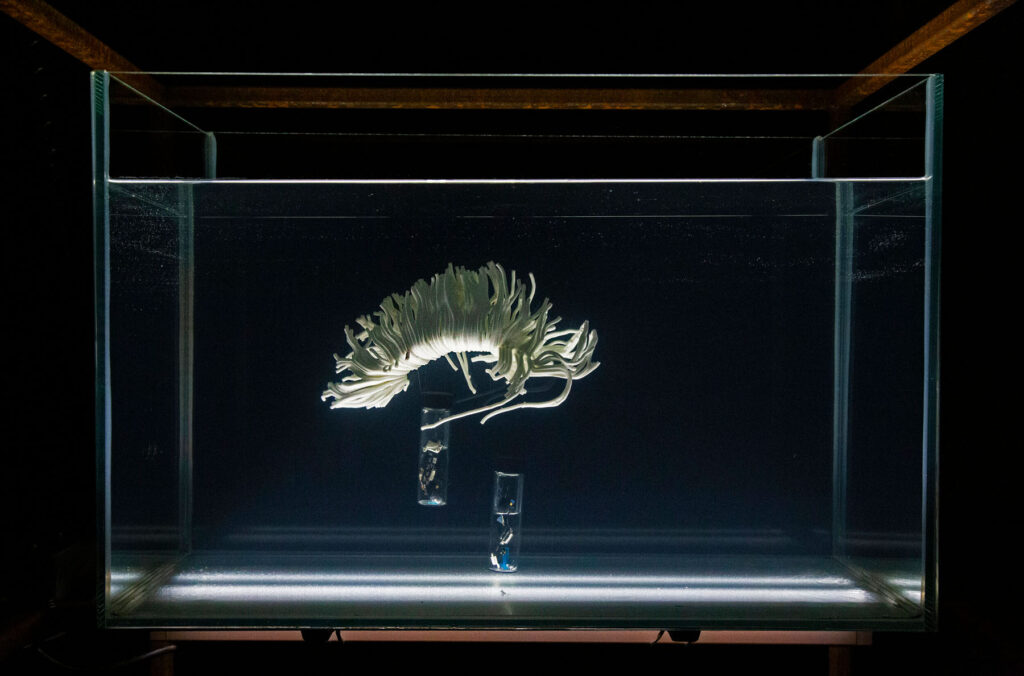

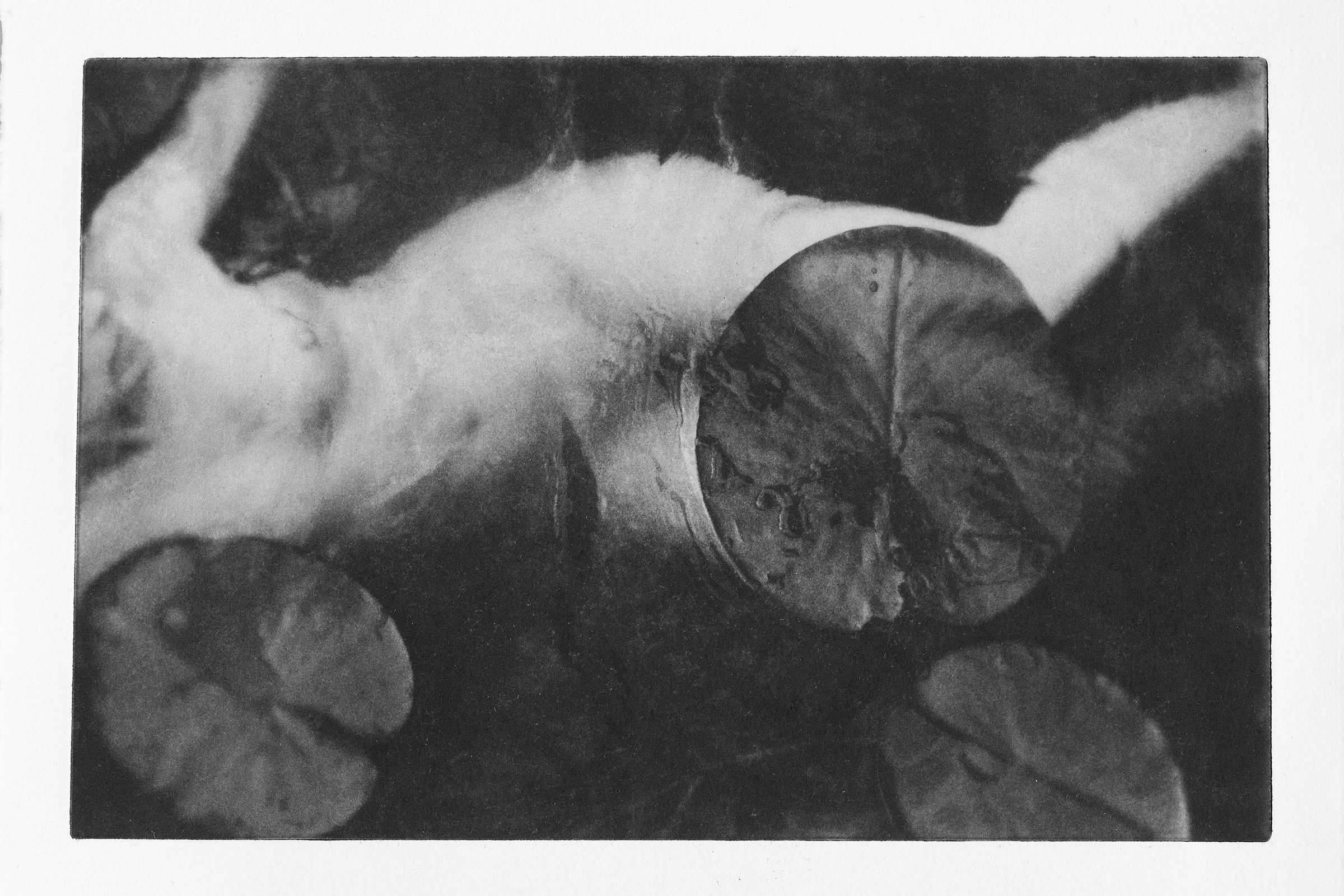

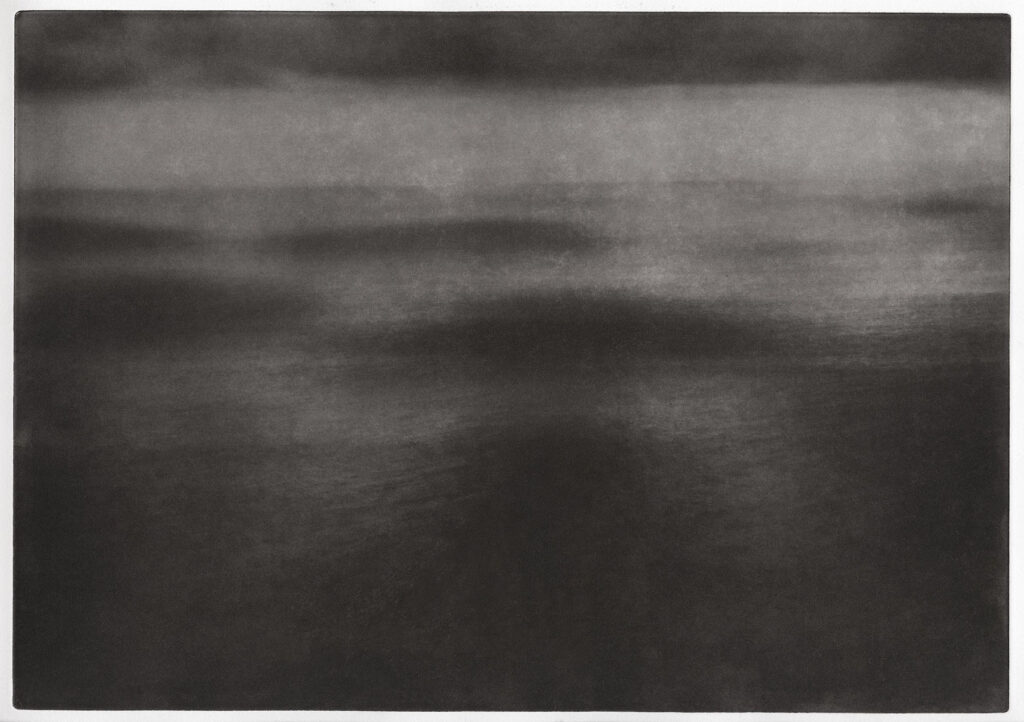

Where Are You #1: The image is taken by the moonlight, imagery of Taoism, and the yin energy that brings the viewer within. The feeling brought me to remember the memory of my sister drifting away.

Where Are You #4: In my dreams, I was running fast to see glimpses of my sister. When I saw a figure running, I thought it was her.

Where Are You #11: I know it is not her, but it is the vague figure that is moving towards me that makes me think it is her.

Where Are You #20: Ever-changing clouds, floating on air.

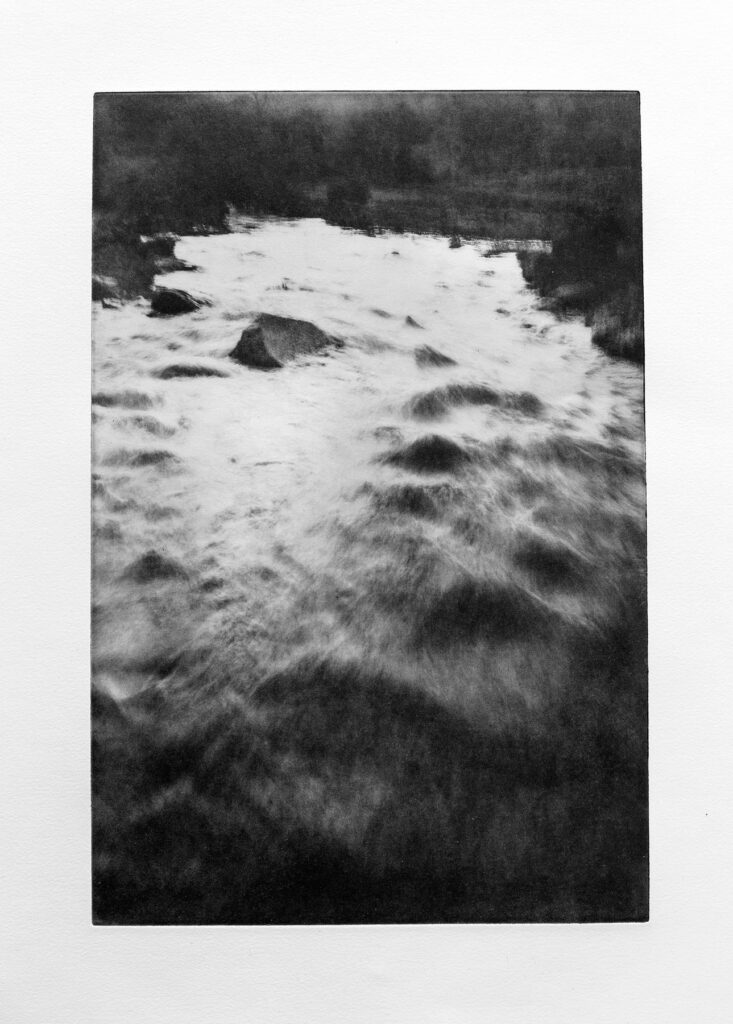

Where Are You #18: The sea, the waves, the clouds, the sun behind the clouds, the rays of light coming in. Here, there is a play between the dark and the light, the light and the dark. I was fascinated by it: it moved me in ways, it made me feel emotional, it lulled me into it, and it connected me to the ones I lost.

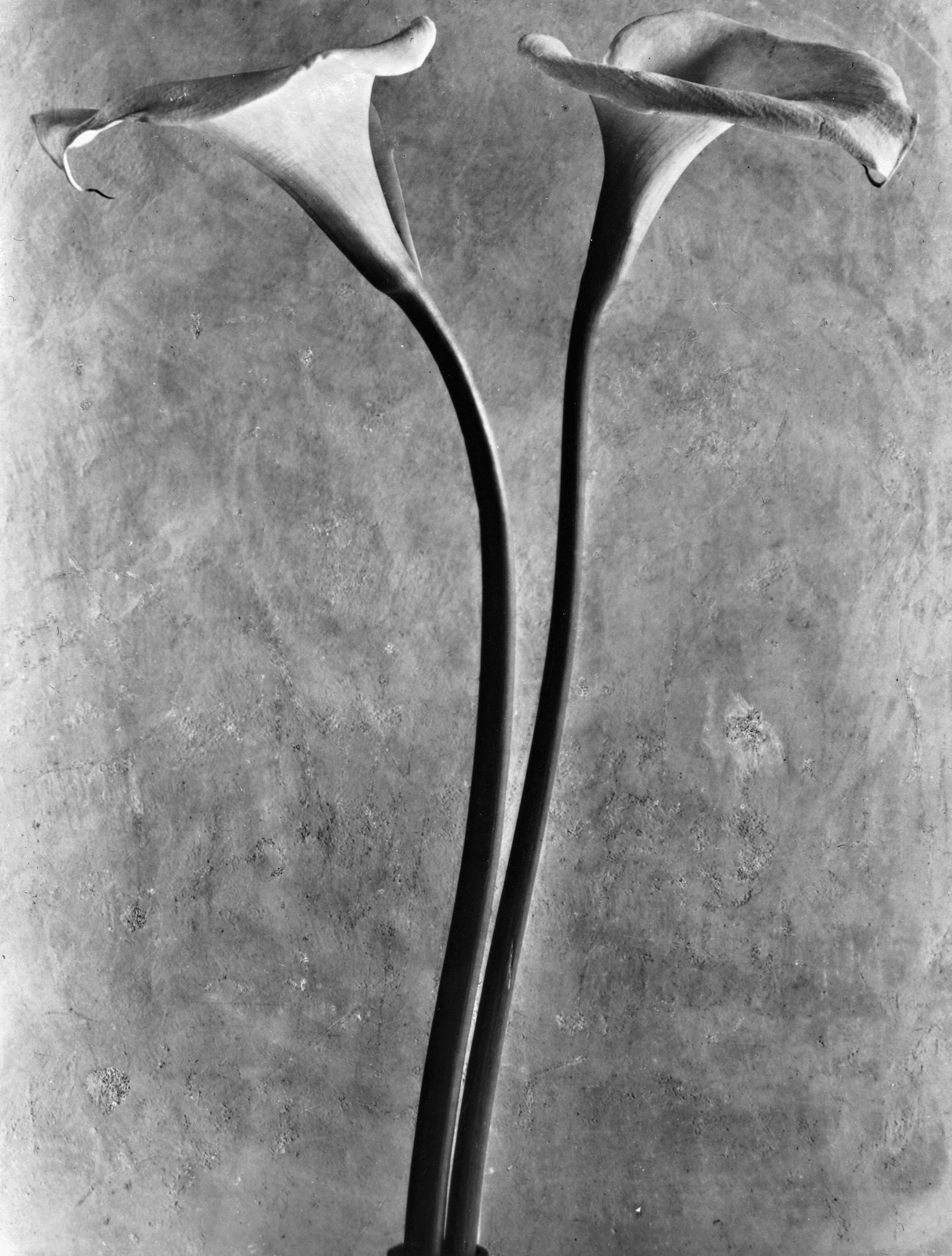

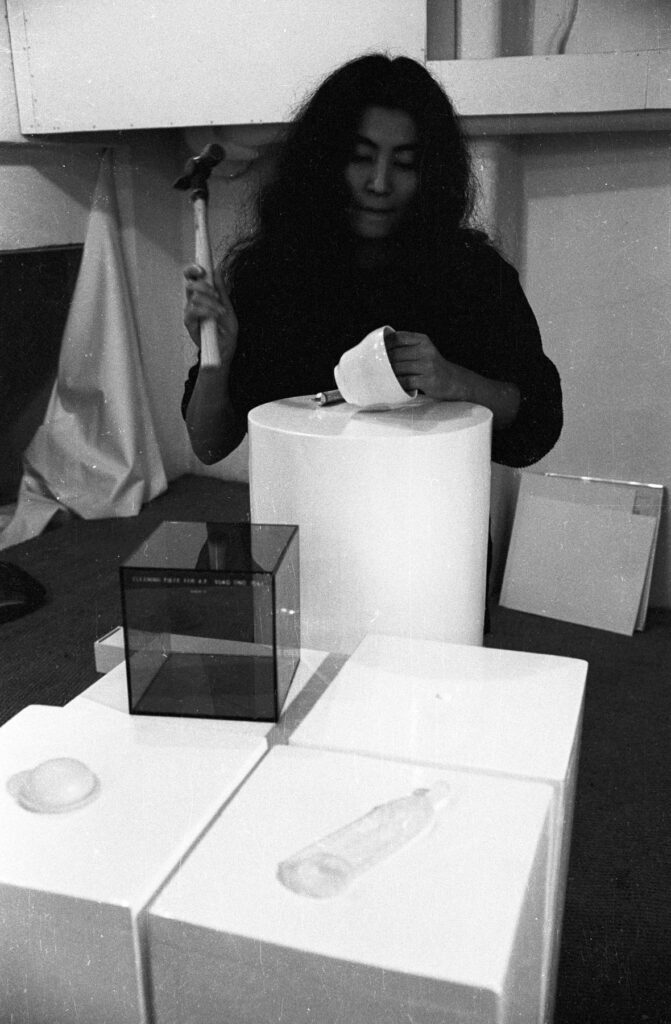

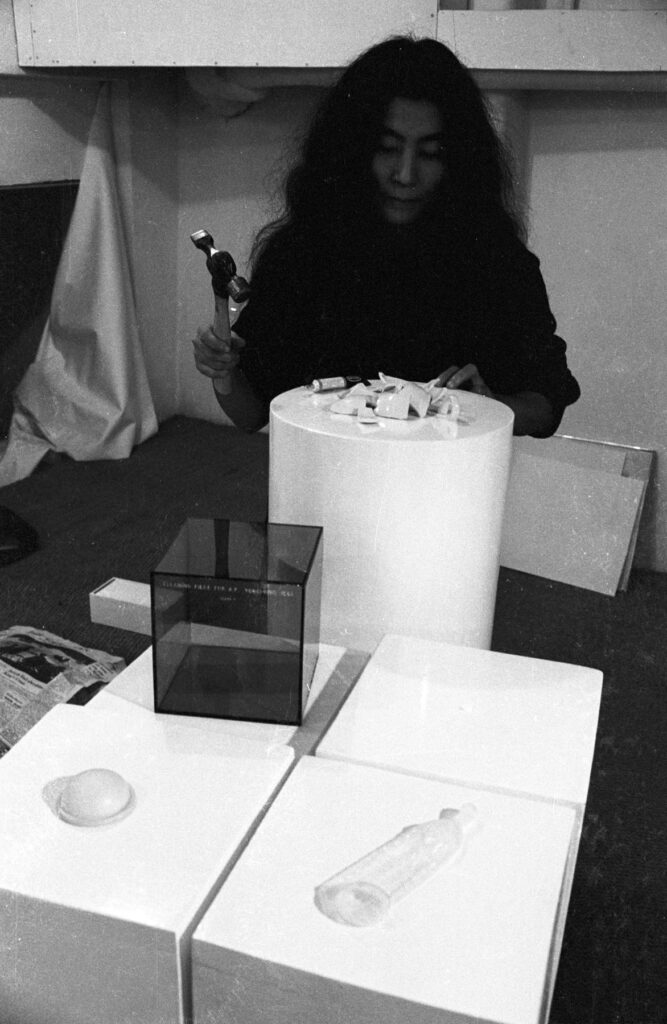

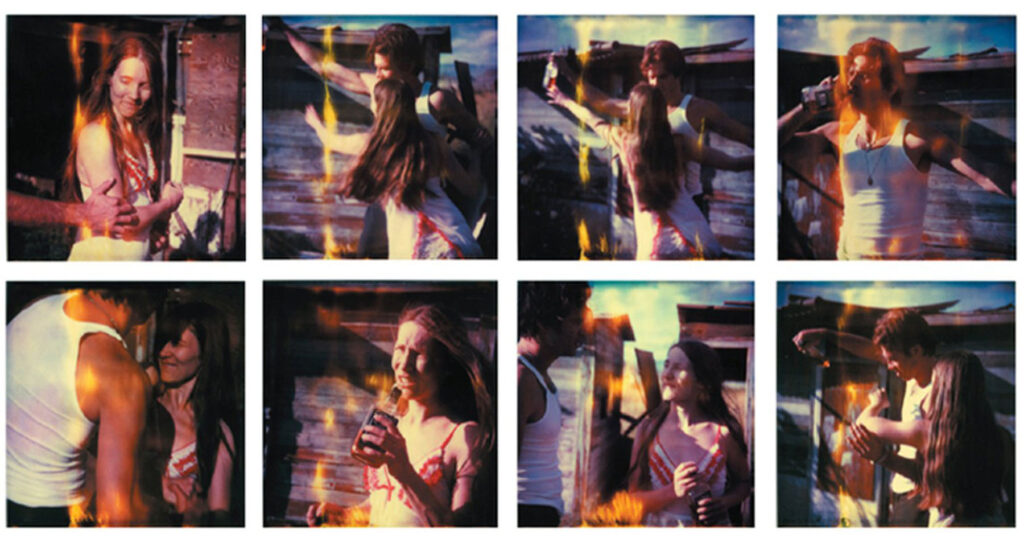

Unfinished #2: Here a teststrip of Marijn, I started photographing with her and still do, she became my muse.

In this image she reminds me of my sister, Nathalie.

Monologue Intérieur seems to be a photographic conversation between who you are and what you feel, an inner monologue associated with thoughts, fears, and emotions that come and go. Have you ever latched on a single emotion and found it difficult to let go?

The inner monologue is often associative. Thoughts, moods, feelings come and go. I try to catch these in order to be moved by the image. It is not only about my feelings, but my models’ as well.

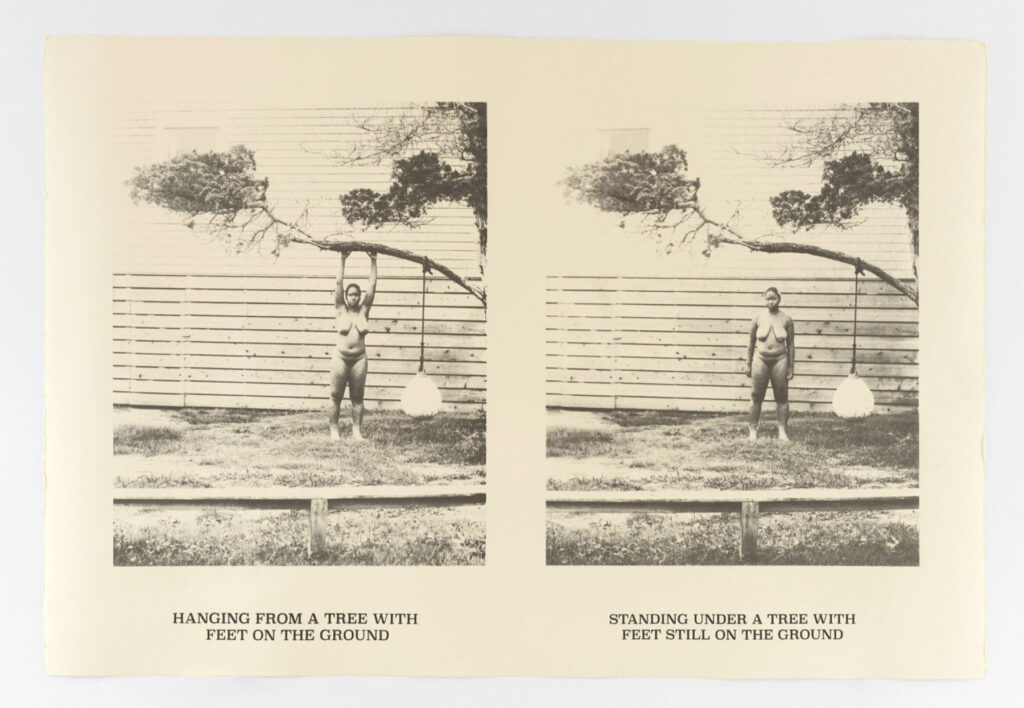

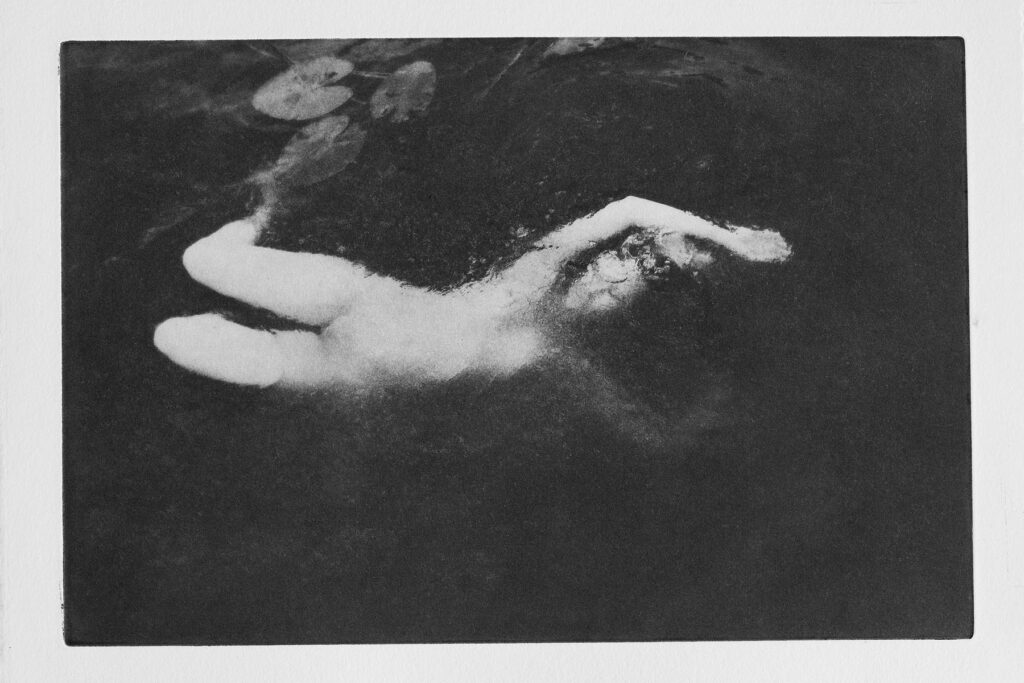

Nude photography can be a complex subject to me. It is about finding the purest and most liberating expression of strong femininity. It is combined with the inner monologue, transforming the images into layers of stories.

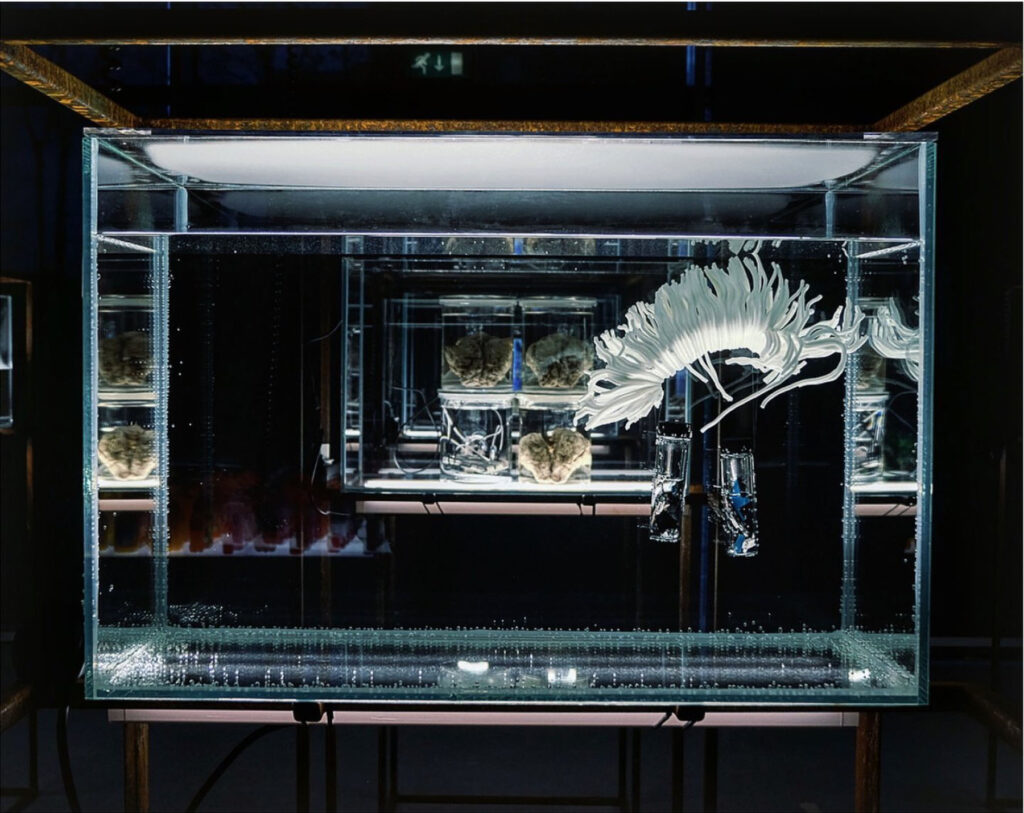

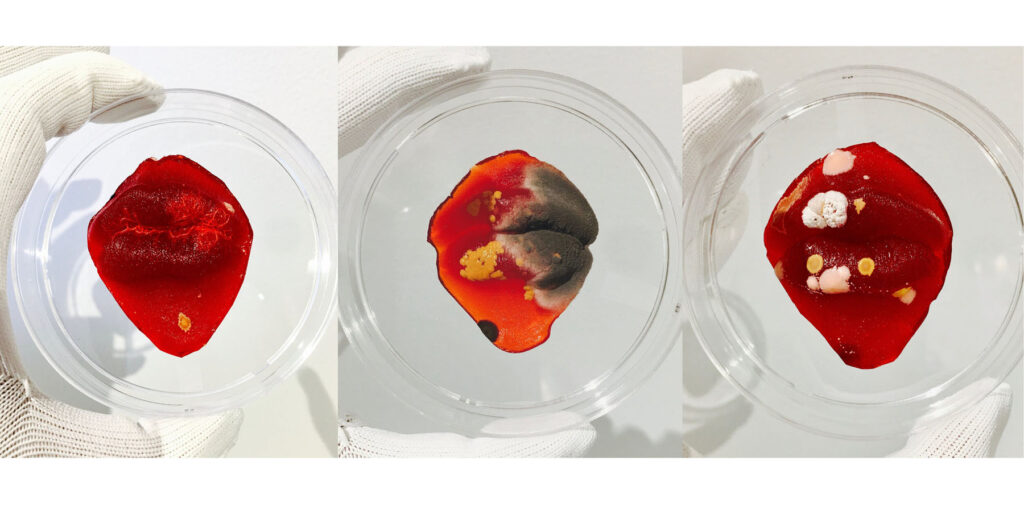

Water as a purifying, transformative, and healing gift of life. In Healing or drowning, water becomes the symbol of existence, the power of connection, softness, surrender, and forgiveness. When do you seek healing? Is it hard to surrender yourself to the flow of the universe? How do you forgive – by forgetting?

I seek healing especially in times of grief and turbulence like the last one and a half years, where we have all gone through certain waves.

“Surrendering to the flow of the universe is a never-ending challenge.”

For me, forgiving is not about forgetting. I think it is a process that experiences ups and downs, highs and lows like waves that come and go, trying to find the angle of compassion for others. I think these bring in the softness, the healing part, for others and myself.

You quote T.S. Elliott as part of your artist’s statement. “So the darkness shall be the light. And the stillness the dancing.” How do you relate to these words?

The words refer to my own process that started with the death of my younger sister. I went through deep grief, a depressing period, trying to find the light. This is why I started my series ‘Where Are You’ with specks of black and bright white.

If I had to go to a deeper layer of myself, I think I would uncover stillness while finding my way out, accepting that nothing will ever stay the same and that love never dies.

What’s next for Chantal?

I’m looking forward to some wonderful collaborations in Japan, Italy and Sweden and a period as Artist In Residence to be able to do research, experiment and deepen my work.

Credits

www.chantalelisabethariens.com/