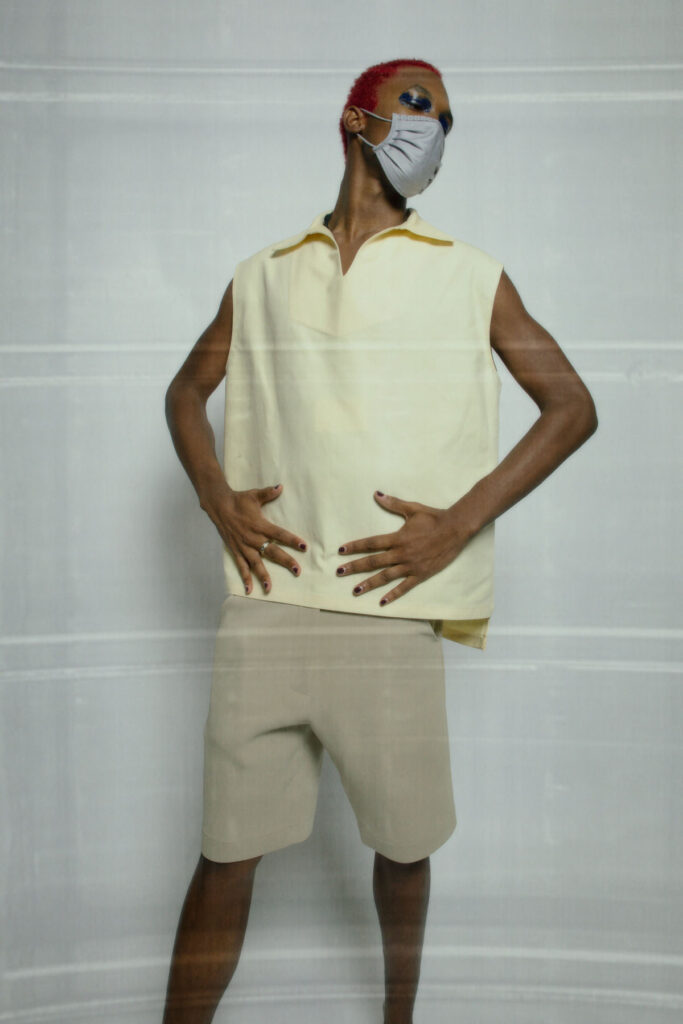

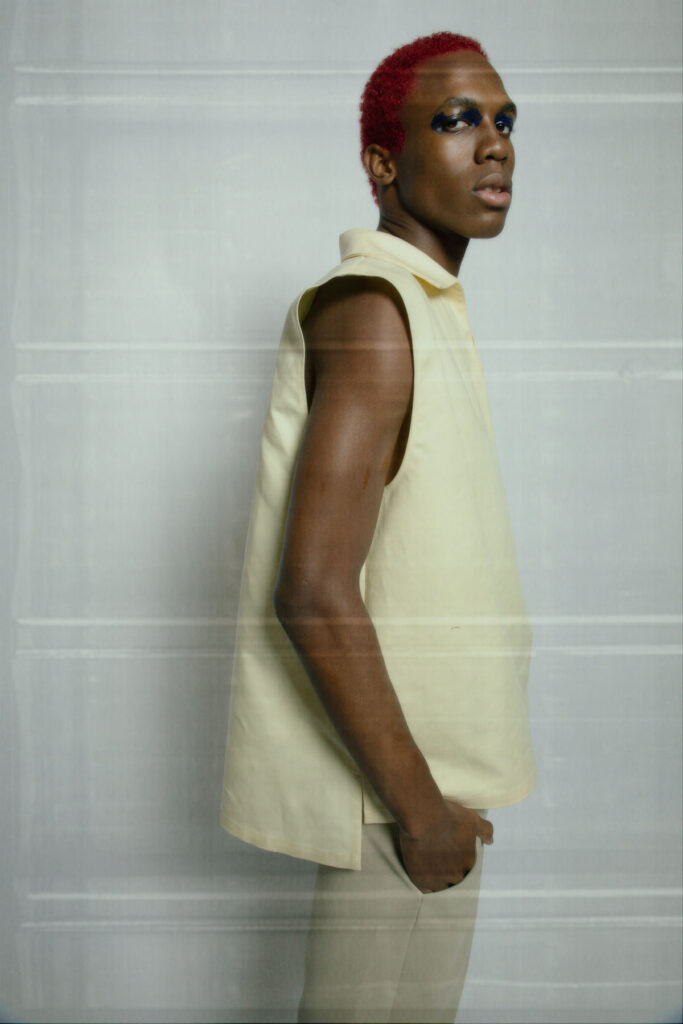

«It began as a necessity, and quickly became a FUNdamental step of my process»

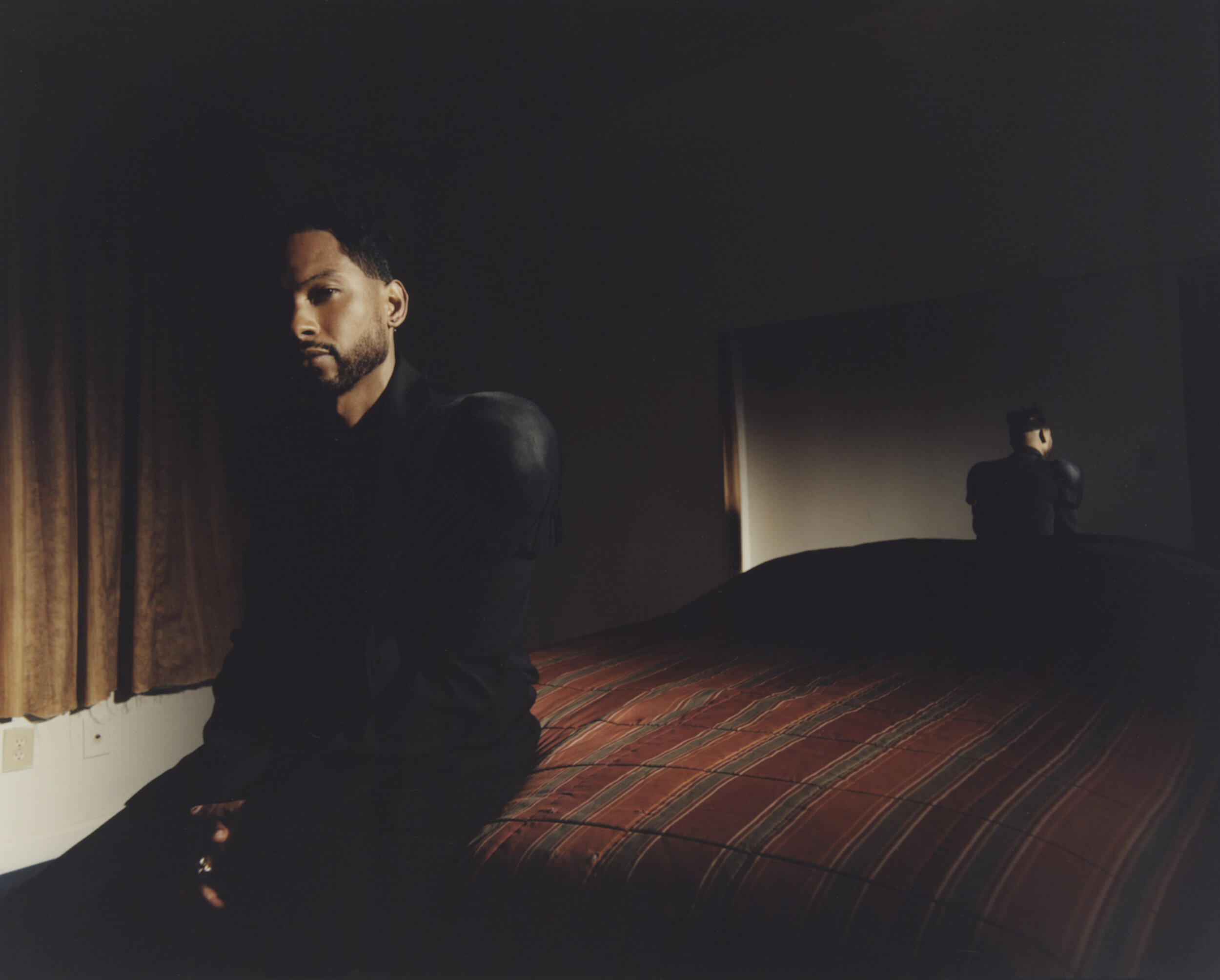

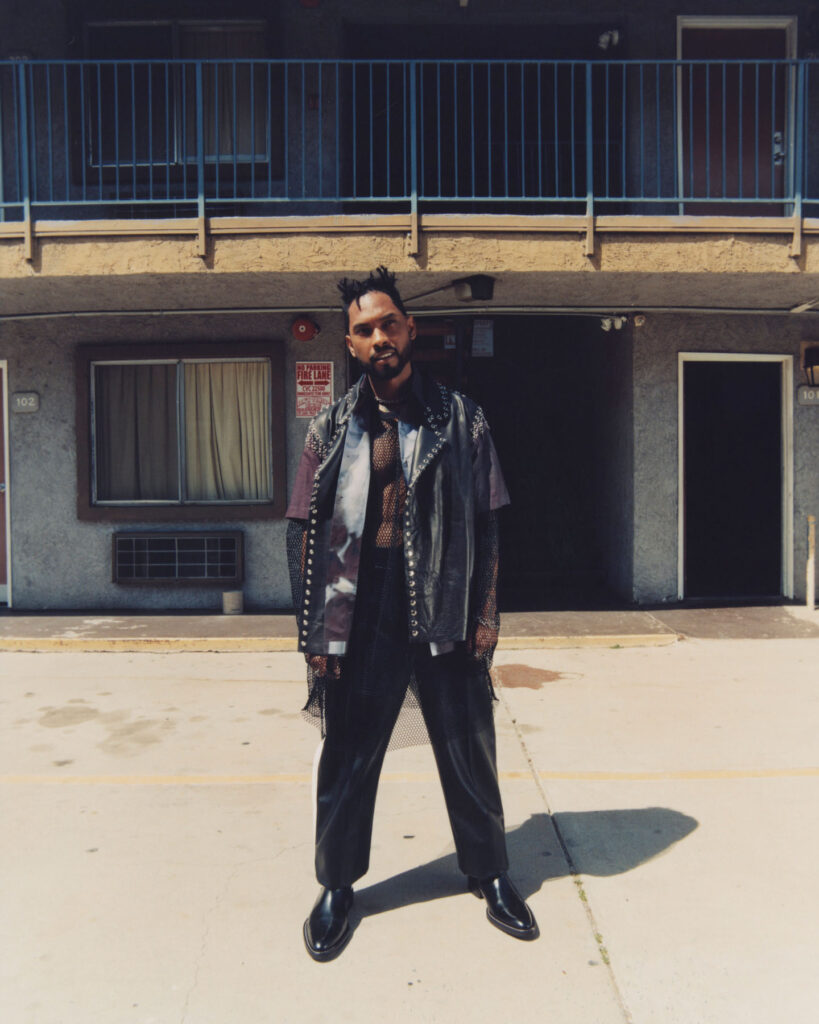

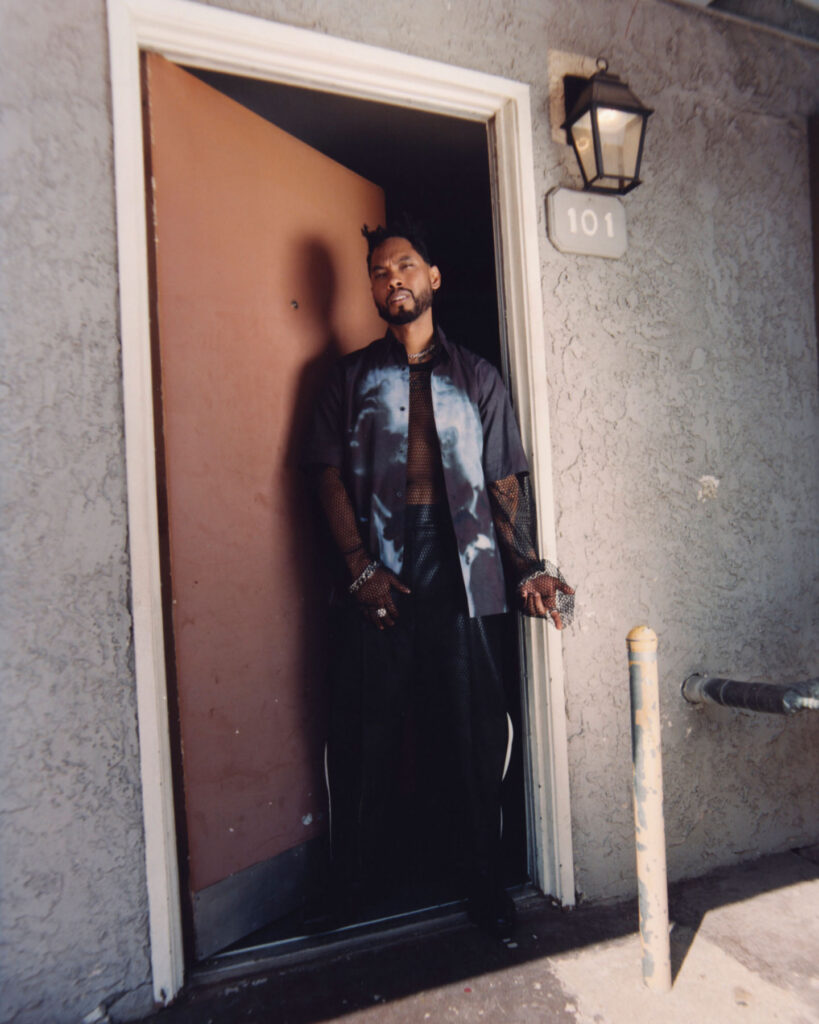

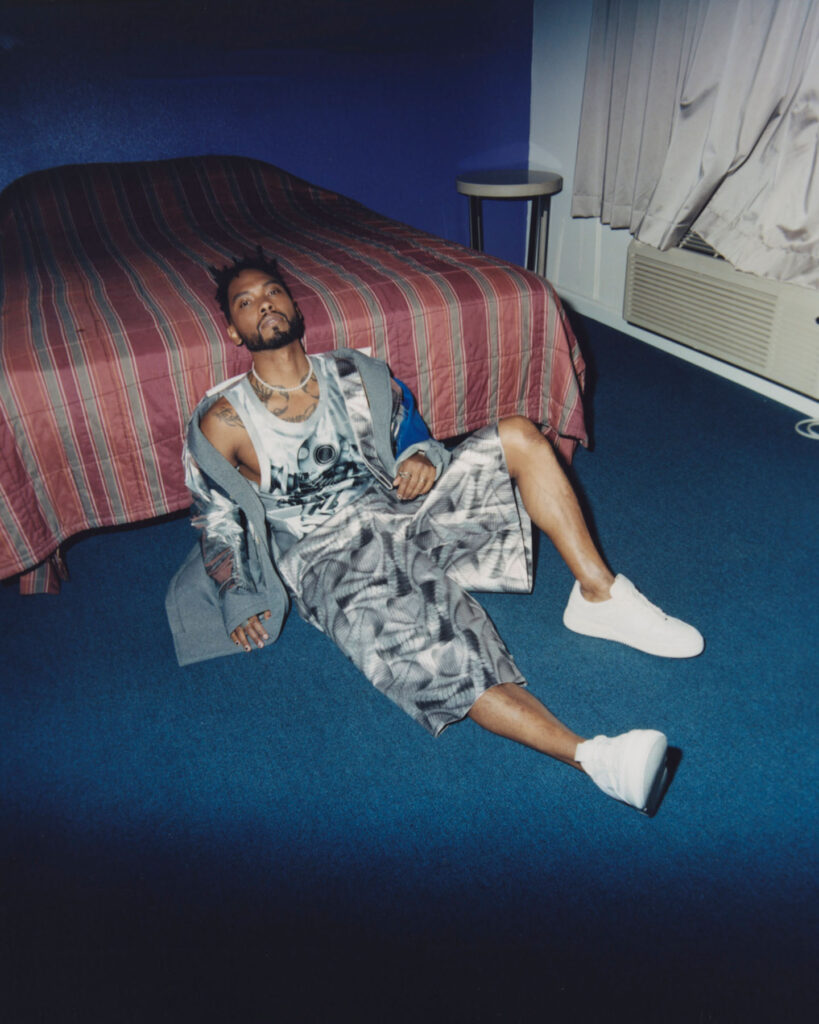

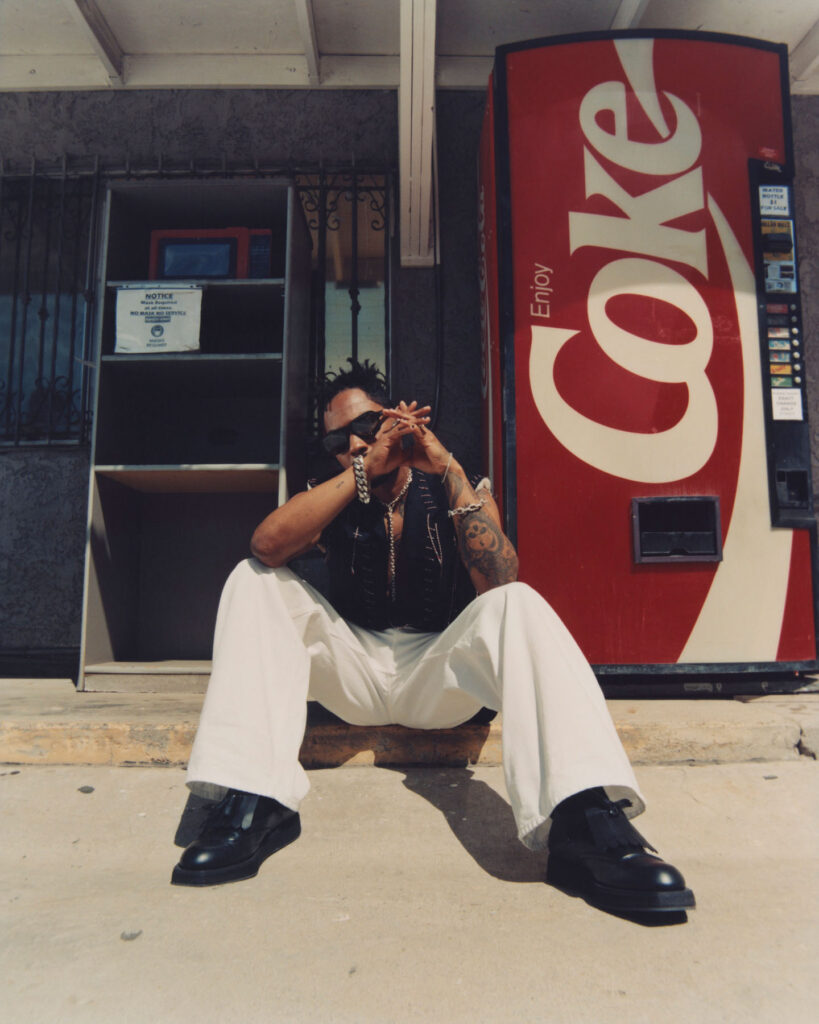

To paraphrase Fellini, things are not always what they seem. It is incredible how individuals’ minds can correlate images, objects, colours and shapes which do not originate from the same context. His name is Vivien Canadas, and his latest collection, A sip of fresh air, is an ode to visual culture and its boundless limits.

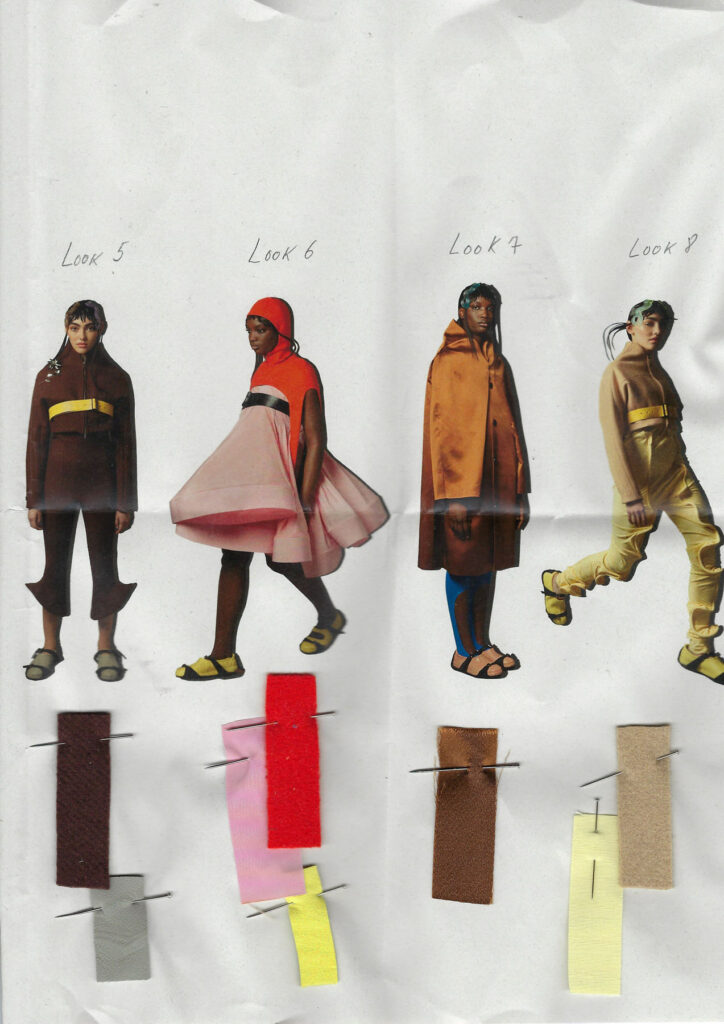

If I were asked what tortellini and a handbag have in common, I would probably call my grandma, asking the same question. On the other hand, the recent Central Saint Martins MA graduate, might have something to say about it. Taking inspiration from the simplicity of everyday life, the French designer took us on a wonderful journey across his process and peculiar eye for silhouette and shape.

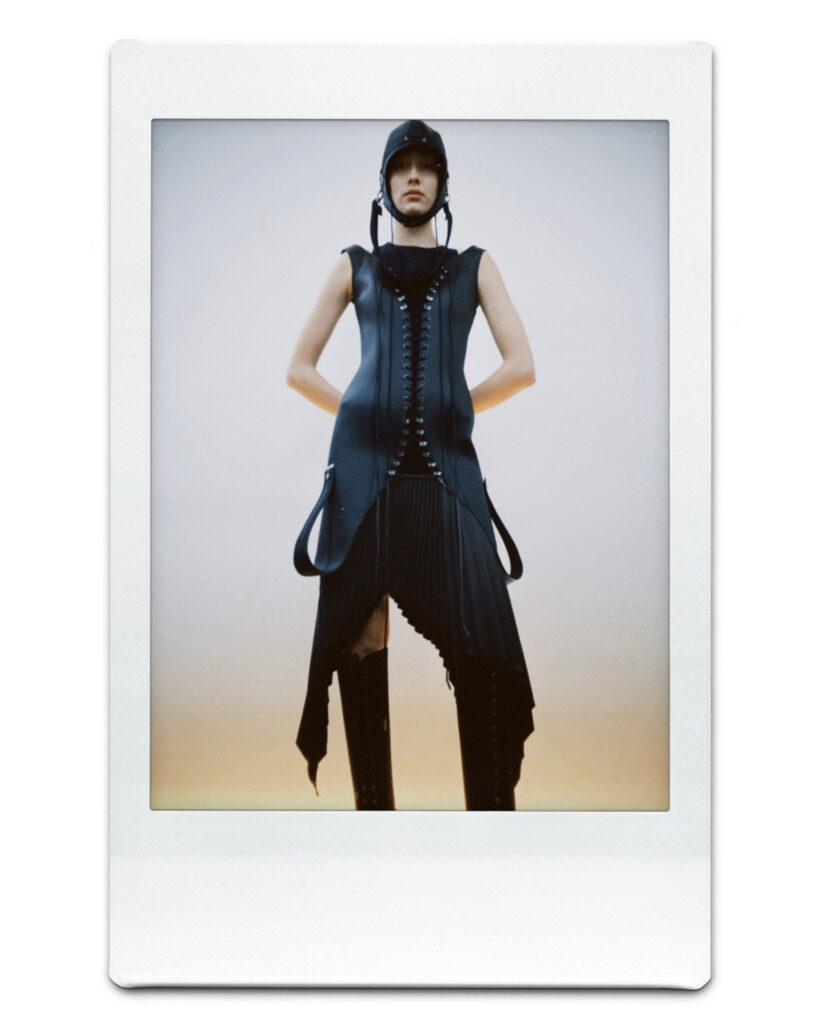

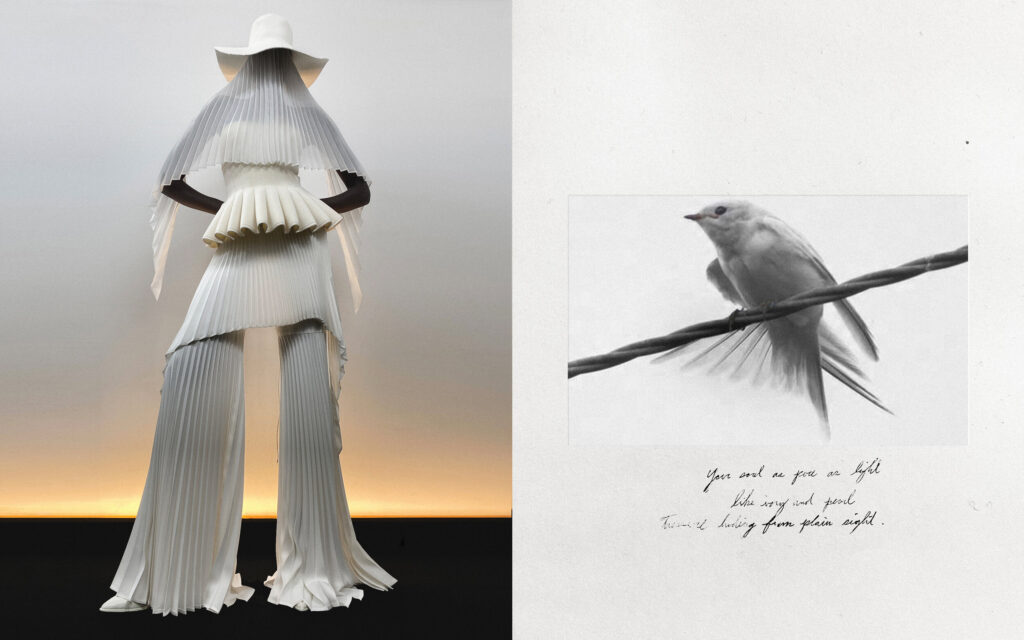

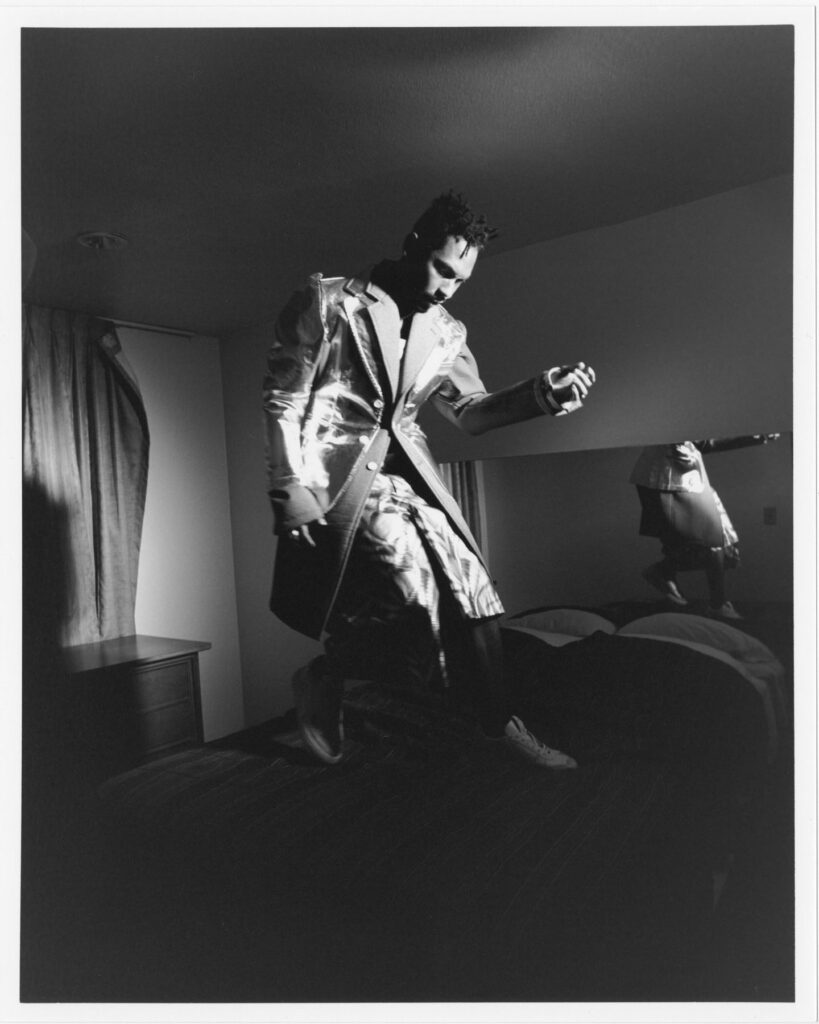

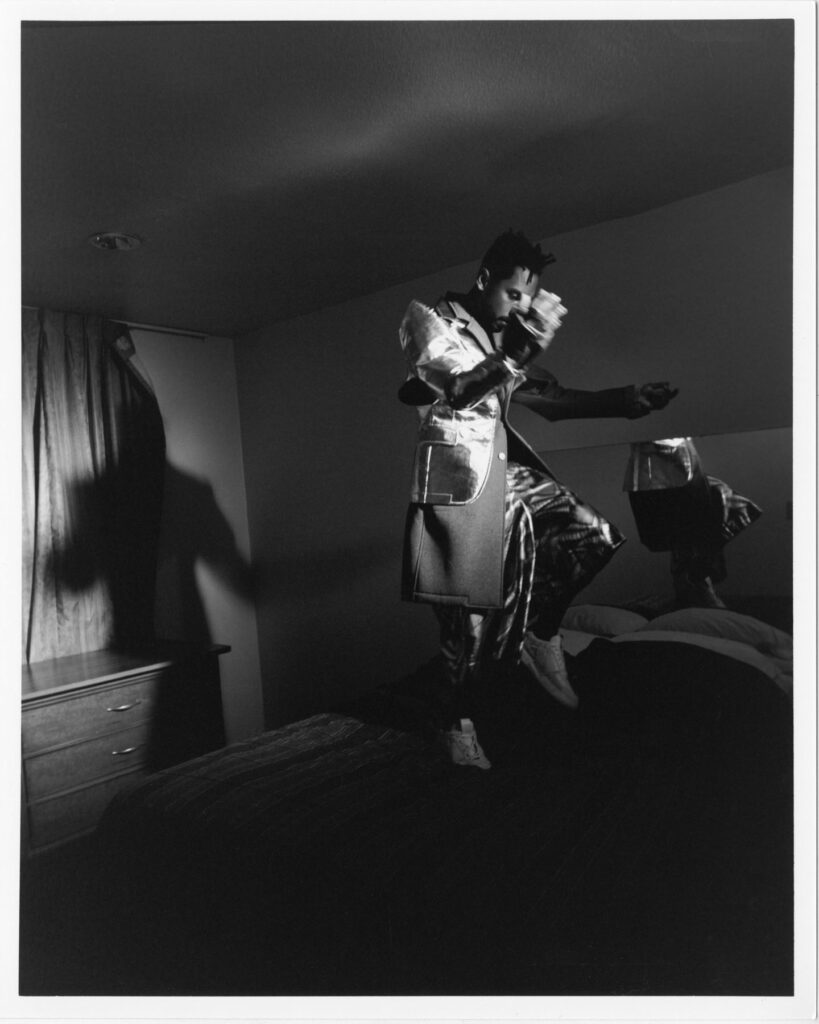

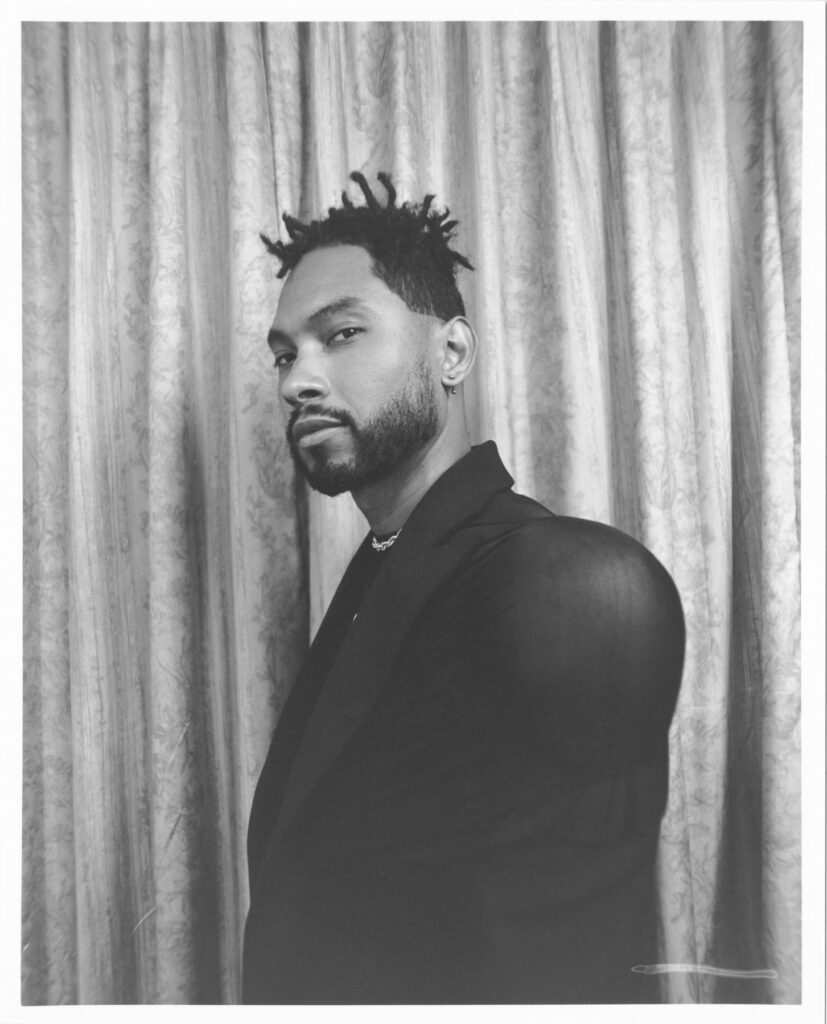

“To show humour, but also recall some kind of old-fashioned elegance” points out Vivien. The collection struck fashion’s preconceived notion of mundanity, and here we are, a second later, witnessing the evolution of a trumpet, into a pair of trousers.

Being able to surprise the world with such a brilliant MA collection, followed by your project in collaboration with Tod’s must have felt as an incredible achievement, congratulations!

Tell us more about your vision and inspiration in the process of making it.

Thank you for your kind words! I’m very glad, my final collection and my Tod’s project caught the eye of NR Magazine. My design reflects my fascination for the ordinary and mundane. Through my research I visually collect artefacts, explore customs and incorporate these elements into my draping process. A trumpet evolves into trousers, a tortellini becomes a bag etc. A playful approach that does not intend to be literal. I aim to create a silhouette that shows humor, but also recalls some kind of old-fashioned elegance.

Part of my draping process for my MA collection was about recreating the movement of a garment caught in a storm. I designed voluminous skirt and dress that were based on a simple circle of fabric. Using such a shape was a direct reference to Christian Dior and his New Look silhouette. Subverting traditional techniques and volumes used in Couture is fundamental in my process.

Your collection, ‘A Sip of Fresh Air’ is an open invitation to escapism, to look at things under a different light. What would you like people to reflect on when looking at it?

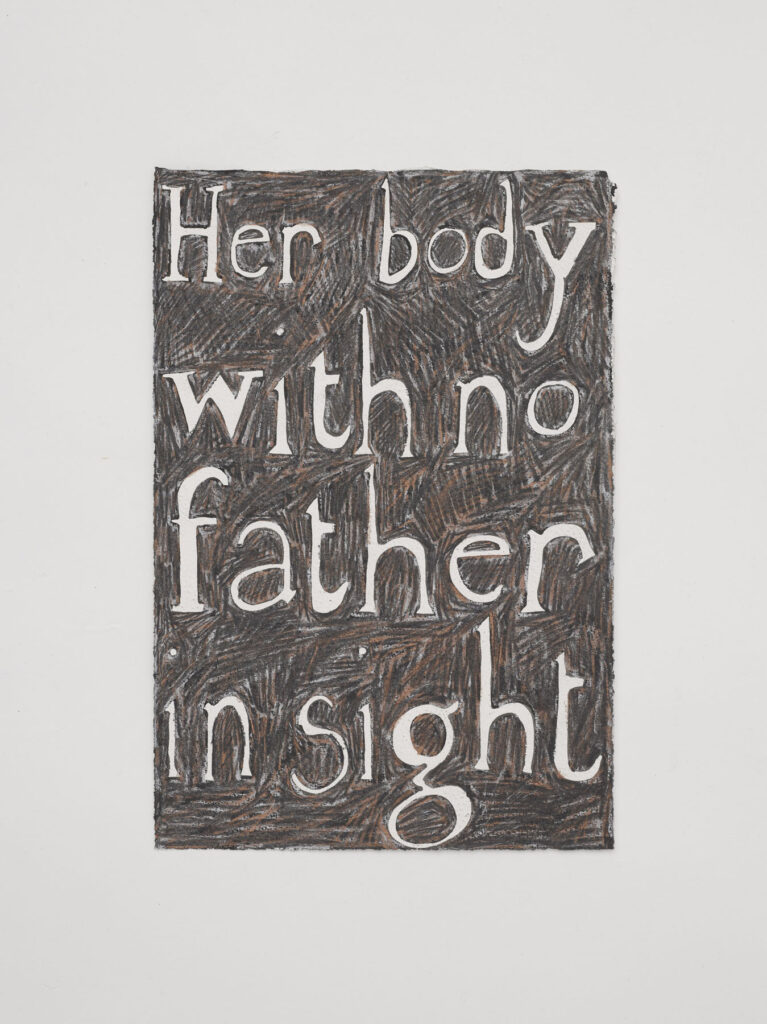

In less than a century, humanity has completely transformed its natural habitat by escaping the countryside in favor of the city. A radical mutation that built some form of nostalgia.

My collection is an invitation for a city getaway.

«A moment to reflect on what is ‘modernity’ and how the ideal of countryside life redefines or transforms this concept.»

It is a celebration of the bridge between traditions and Mankind’s – perhaps odd? – progress.

The wind is blowing and taking everything on its way. Full skirts are flying, coats are pushed on the front of the body. “A sip of fresh air” is also about re-iterating and re-thinking our temperamental relationships to the elements.

Tell us more about Tod’s and the ‘Tortellini bag’.

For my project for Tod’s, I decided to explore the Italian food culture and gastronomy. One of the main references was the movie Roma by Fellini. A scene in particular was key to me: It’s evening and people are eating on a restaurant’s terrace.

«A moment of life that depicts with humor, and splendour, the Italian cuisine and its mise-en-scène.»

I was intrigued by the construction of the Tortellini. An emblematic ring-shaped pasta dish that is made from a flattened square dough and stuffing. Following the same construction, I thought of adding Tod’s elegance to the recipe. The result? A funny shoulder handbag in various colours.

Can you talk us through the collaborative aspects of your MA collection?

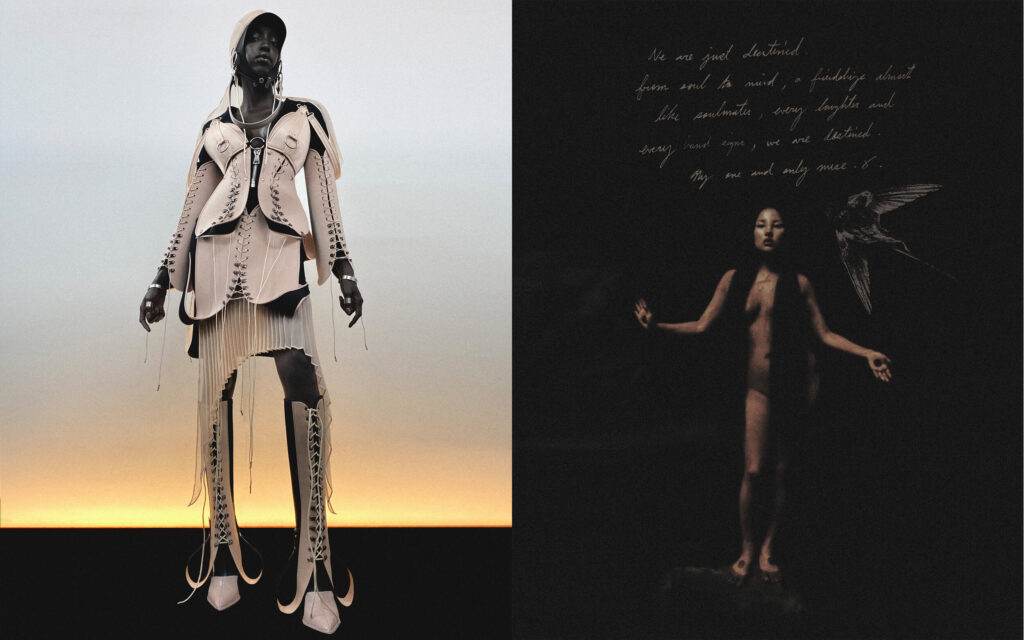

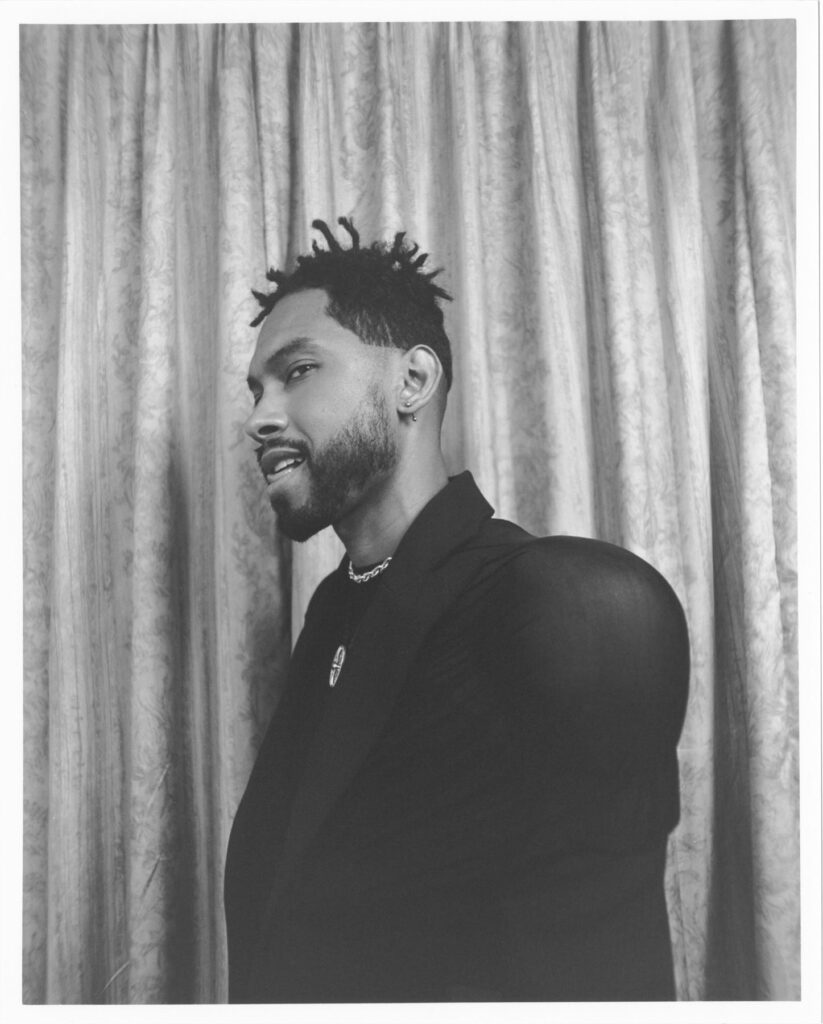

Fashion is about sharing. It is a human adventure that reaches its fullest when you get to collaborate, interact and create with others. I couldn’t imagine this project to be only about my own exploration. I wanted to incorporate other visions, and give them the space to express themselves. The shoes were designed in collaboration with Baptiste Faure. They are made from recycled Wellingtons, reworked into a pair of shoes, suited for urban life.

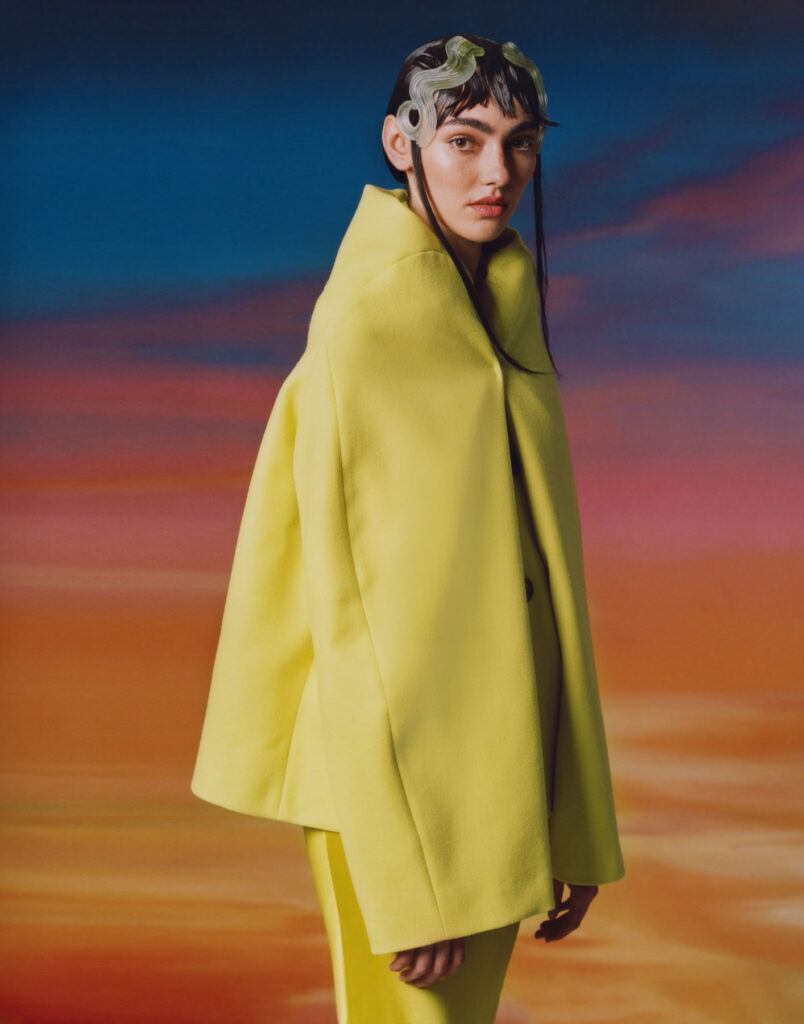

Collaborating was also a way to celebrate Daum’s savoir-faire, a crystal company founded not far away from home-town, Remiremont – France – in 1878. Using their unique craftsmanship of casting and colouring crystal, we designed “trompe l’oeil” headpieces. Resembling wet hair, the prosthetics reiterate our temperamental relationship with the elements, but also reflect my desire to build a new bridge between tradition and modernity.

The global circumstances in which you found yourself developing such a high caliber of work must have not been the easiest ones. In what way have you managed to adapt your practice to such a restrictive situation? What have you learned from it? How did you adapt your creative process to it?

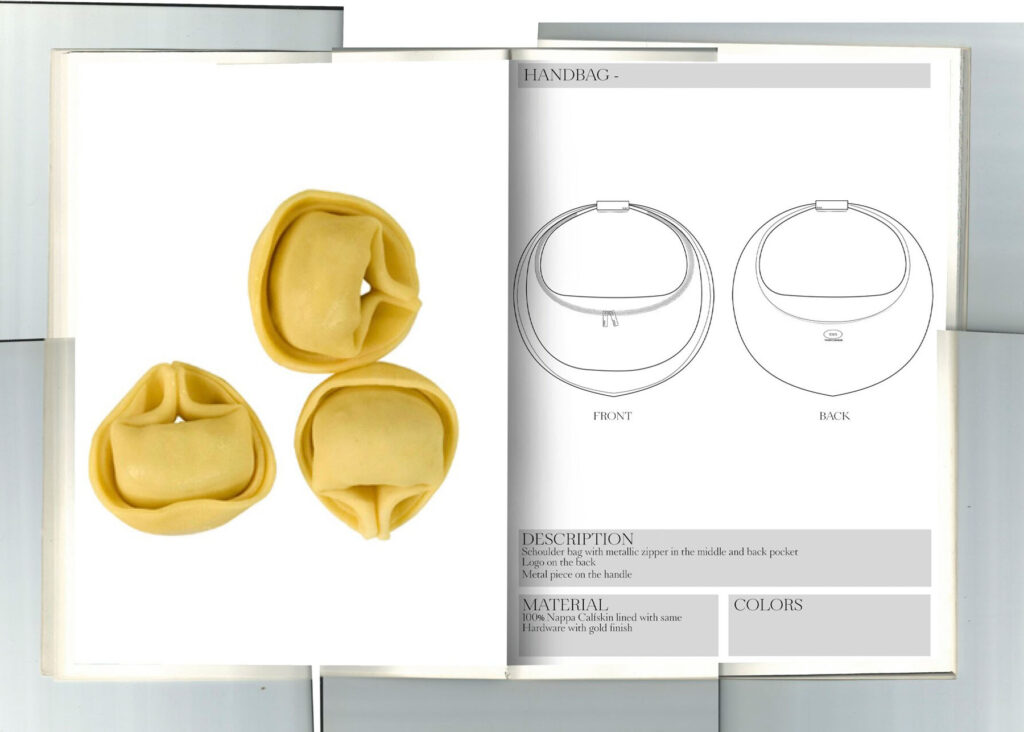

Working on these projects was a chance: it forced me to stay resilient and pro-active despite the world situation. The lockdown pushed my process to evolve: more than ever before, I used my own body for my draping experimentations and fittings.

«It began as a necessity, and quickly became a FUNdamental step of my process.»

Things might not go the way you are planning, or you might not have the fabric you wanted: this experience taught me the essential value of being flexible.

Your journey into fashion started long before applying to CSM. Tell us more about your background and training.

Following a Masters degree at Sciences Po, Paris, and after completing a couple of internships, I worked as a junior designer at Maison Margiela for almost two years. Not your typical pathway… I hadn’t formally studied design before commencing the program at Central Saint Martins!

Looking at fashion Today, what are your hopes and concerns?

I hope fashion could go back to a more human scale.

The urge for relevancy in the work we produce has never felt more important than now. What do you have to offer?

As fashion designers, we are not only developing garments, we are creating a world. As a matter of fact, it is essential to take part in the ongoing conversation, and to reflect on the message behind my work. It appeared crucial, within my process, to understand who I am and what I represent, in order to support a progressive message that acknowledges and elevates others, no matter which gender, race, sexuality…

What can we expect to be seeing from you in the near future? Do you have any new projects coming up?

I would love to keep working on my own practice, and see where this takes me.

Credits

Images · VIVIEN CANADAS

https://www.instagram.com/viviencanadas/