“standing with one leg rooted in the world of science and the other leg rooted in the world of art”

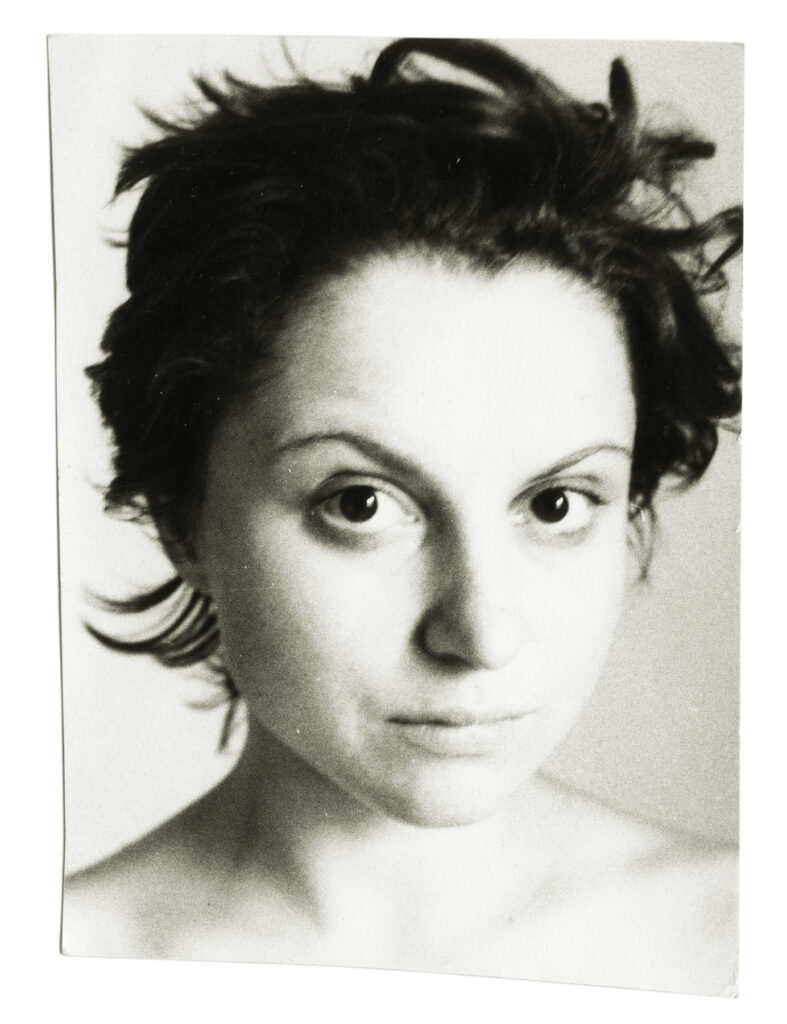

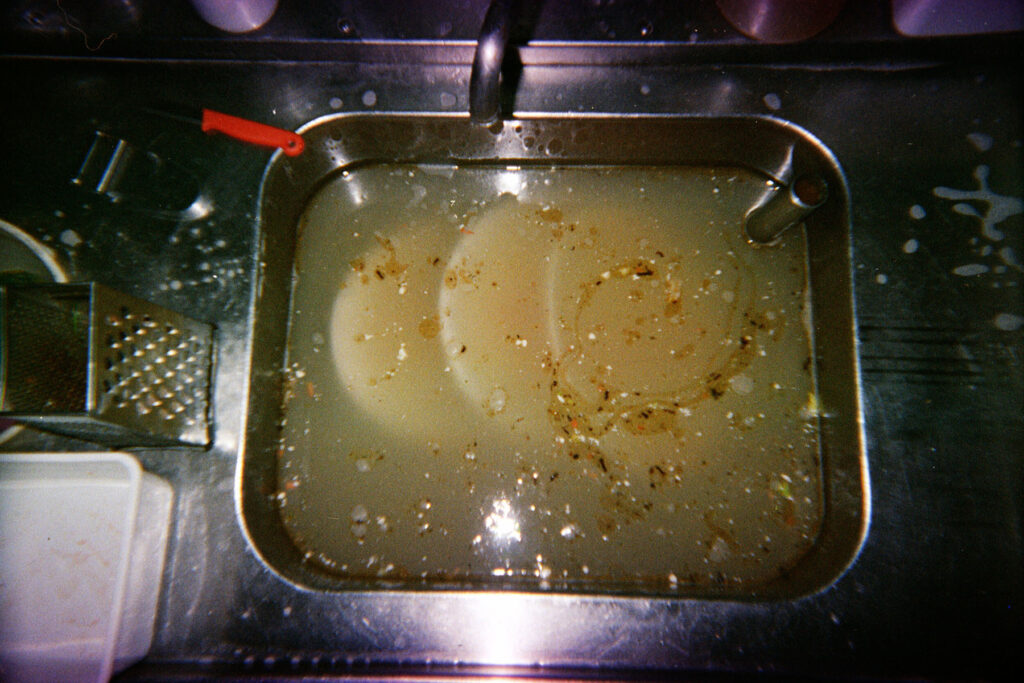

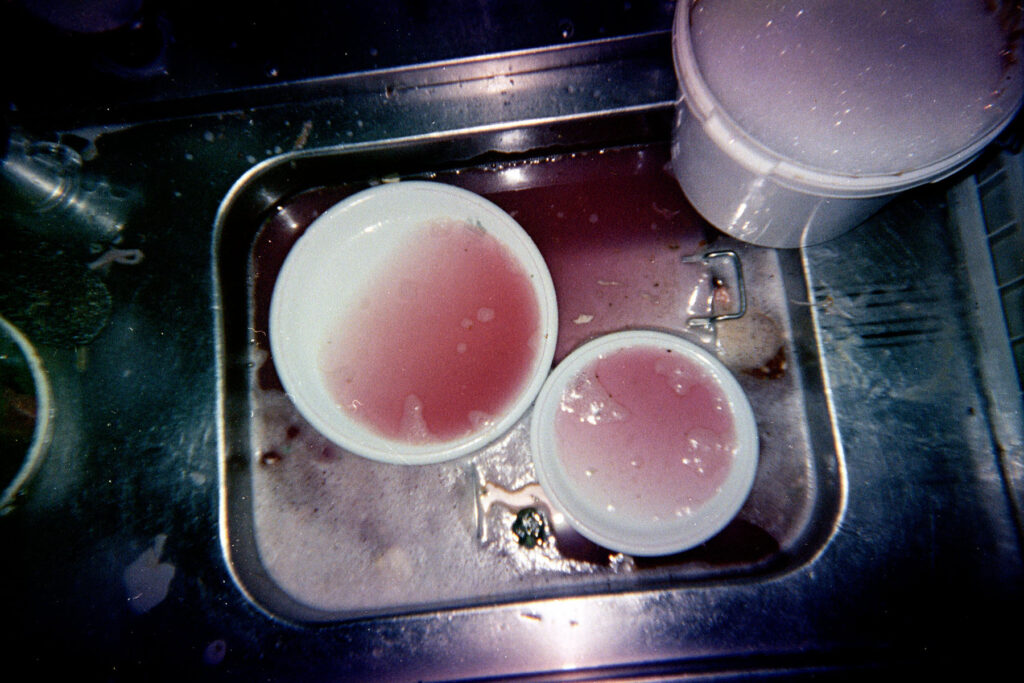

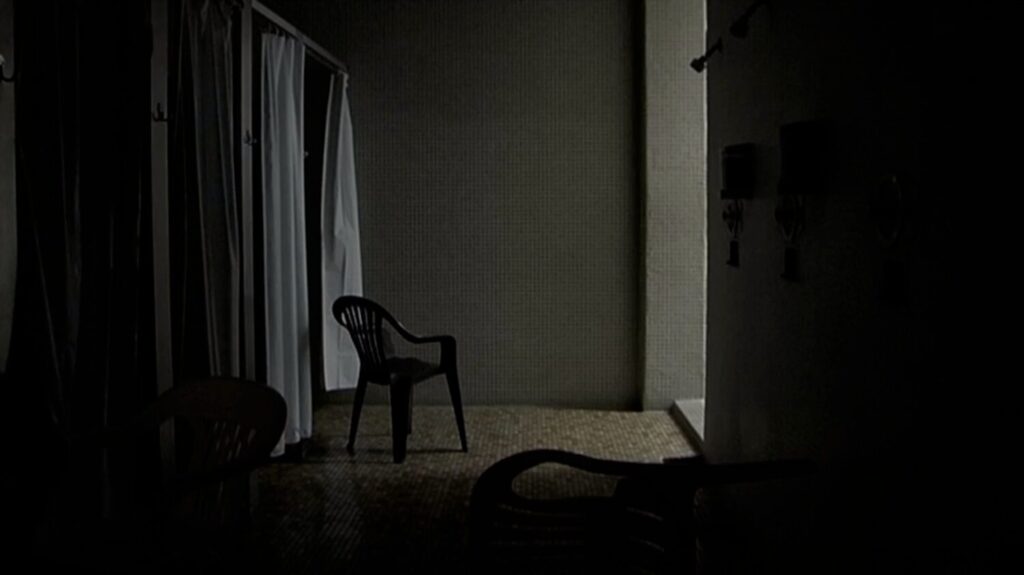

Distorting bodies and exploring the intersection between painting and photography, Danish photographer Henriette Sabroe Ebbesen explores aspects of the surreal and works with reflections and collage to craft unique landscapes and new realities. Investigating the painterly potential of photography as a medium, Ebbesen distorts our sense of reality by manipulating the objects and space within the picture frame, and prompts us to question the truth in what we see. Ebbesen’s work also addresses concepts of identity and the subconscious, with a particular focus on the relationship of the self with the surrounding world.

Alongside her artistic pursuits, Ebbesen studies medicine, which she finds to be a great influence on her creative process – particularly the neurological processes that take place when creating a piece of art. Intrigued by the laws of and structures of the physical world, Ebbesen draws on this knowledge to build her collection of odd imagery that she creates intuitively, informed by the subconscious mind that is often in opposition to the logical thinking favoured by the field of science.

The vibrancy and fragility of the natural world imbue a sense of tranquility within Ebbesen’s work, and her detailed exploration of memories and conflicts within her personal life establishes a vulnerability and charm to her practice.

NR Magazine speaks with Ebbesen to learn more about her creative process and to discuss the relationship between art, science and identity.

Your work plays a lot with reflections and collage to create a unique sense of the surreal – how did you come to develop this style of working?

I’ve always had an experimental approach to my work. I started to experiment with distortion because I wanted to create work that bordered painting and photography. Distortions could give me this interesting effect. I use different kinds of mirrors and reflective material to create the distortions and illusions in my work. I only use Photoshop for colour and light editing. It is both an experiment for me to see how I can create an illusion with the mirrors, but I also want the viewer to question what they see when they see the finished work. Practically speaking, I try to bend reality and capture it with my camera for the viewer to experience a different reality than the one they are used to.

Collage comes into my work in my series ‘Growing Up’ where I mix my own photography with childhood photos from our family album. This work is a bit like making a puzzle or a digital painting.

Your work also deals with concepts of identity and the subconscious. Were these concepts always something you sought out to explore? With the theme of this issue being Identity, I’d love to discuss how you feel you explore yourself and your identity through your work.

When creating my work, I feel like I discover bits of myself piece by piece. This comes from the creating process and from analysing my own work where I feel like thoughts and memories from my subconscious mind suddenly take place in my conscious mind. By becoming aware of my subconscious thoughts, I feel like I learn things about my own identity that I think I could only learn though the art-making process.

Does living in Copenhagen influence your work at all?

Living in Denmark with its dark winters really makes you appreciate the sunlight when it appears. During the long winters I long for warm and bright summer nights and dream myself back to this time of the year.

When the first sun appears in the spring, I love to point my head towards the sun and with closed eyes sense the warmth and light reaching my forehead and eyeballs behind my eyelids. To me, this is a true feeling of happiness, and this feeling is something I try to capture with my camera when shooting in direct sunlight in most of my works.

When winter arrives, I can then look at the work I shot during the summer and dream myself back to this feeling.

Your series ‘Feminine Development’ addresses the alienation of the female body and female sexual identity. You mentioned that creating the series also confronted your own body insecurities. Have you felt this kind of confrontation or self-realisation with your other work?

Yes definitely. My work always has something to do with me and what I have on my mind. I try to create work that challenges me on a personal level. This could be in the form of trying out a new technique or digging into a theme that disturbs my mind. It really depends on the type of series, but I would get bored if my work wasn’t challenging for me to create. As soon as I feel safe in an area of my creative work, I try to move on to the next challenge and create something new.

Is there a specific series that you have the strongest connection with?

I would say my series ‘Growing Up’ as it addresses my personal life on another level compared to some of my other work. I have strong memories from my childhood and think of this period of my life as happy and care-free. I enjoyed re-discovering moments from this time of my life when I was searching for images in our family albums.

Your work also has a real sense of serenity and has a dream-like aesthetic. Do you take inspiration from nature?

I believe inspiration comes from everything I experience and see both on a personal level and what I read and study. I probably get inspiration from all visual impressions I get throughout the day. I also get a lot of inspiration from meeting different people and hearing about their different life experiences and worldviews – it challenges me to think differently. When I have emotional experiences in my personal life is probably when I get the most inspired, but I can never pinpoint exactly where my art comes from. It’s probably a mix of all the impressions and experiences layered in my mind.

The nude body and nature are elements that we know from the real world. I think it’s interesting to place these objects and sceneries in a surreal context as it becomes a clash between something familiar and something odd.

I was always fascinated with science, and I love to play with ideas of manipulating the physical rules of this world. According to the general theory of relativity, you can bend space and time. This is what I try to illustrate in my works by literally bending light rays with mirrors. Mathematical structures, physical laws, botanical plants and so many other things from the natural world are so fascinating that they even seem surreal.

With your series ‘Growing Up’ you mention that you rediscovered pieces of your childhood personality. Could you talk a bit more about that?

I think it’s really interesting to look back at childhood images of myself and other people I know well and try to understand the look in their eyes, their smile, gestures, etc. When looking at these kinds of images I feel like it’s the same soul looking out through the eyes of the child as the adult I know them as today.

“Looking at myself as a child has also helped me understand my own identity better.”

How one’s personality has developed through life really stands out when you look at someone’s childhood image.

You’ve worked with some iconic publications like Vogue Italia and Vanity Fair, as well as other designers and artists. Do you prefer working alone or collaboratively?

I love to collaborate with other creatives because I learn so much every time. Coming from a science background, it’s really satisfying working with people who understand the creative language and process. I would say a mix of both collaborative work and working alone is the best option for me, as I enjoy the collaborative process, but I also want to stay true to my own language and mind, which I work the best with when I’m on my own.

Have you learnt anything new about yourself or your creative process over the past year? I imagine being an artist during a pandemic must have been a big struggle.

Yes and no. I think my daily routine hasn’t changed much, as I could continue my normal routine studying medicine alongside my art-making process, which usually only requires me and a model. On the other hand, I had to postpone my first solo show a few months before it could be held in May in Oslo at Vasli Souza Gallery. Also because of Coronavirus I couldn’t go myself, but generally I think I’ve been in a lucky position during the pandemic.

Your work involves a lot of distortion and manipulation of forms. How do you find the potential for these qualities when looking at your subjects and the world around you?

My work revolved around the boundaries between reality, fantasy and the surreal. Here, photography can do something that a painting, for example, cannot. We have a more realistic relationship to photography as a medium because it’s used to document reality. My technique and photographic style studies where the boundaries are between painting and photography. I started to experiment with distortion because they could give me this interesting painterly effect.

I want viewers to think about what is real in the things we see. In concrete terms, the mirrors I use also function as a symbolic boundary between two worlds, with reality on one side and imagination on the other. Since I study medicine alongside being an artist, I also feel that I’m on the border of two worlds, standing with one leg rooted in the world of science and the other leg rooted in the world of art.

I’d love to know more about how studying medicine has influenced you and your art.

I was always interested in both natural science and art and was never able to choose between them, so instead I went for both. In the future I would like to research the creative process of artists and their art-making. Aside from studying, I always need to express myself artistically. I think I became an artist because I couldn’t hold back from the creative process.

I’m really fascinated by what happens in the brain when you create art, because I don’t really understand what goes on in my own head when I create my own work. It’s a process that to me, seems very subconscious and connected to feelings rather than the logical and conscious mind.

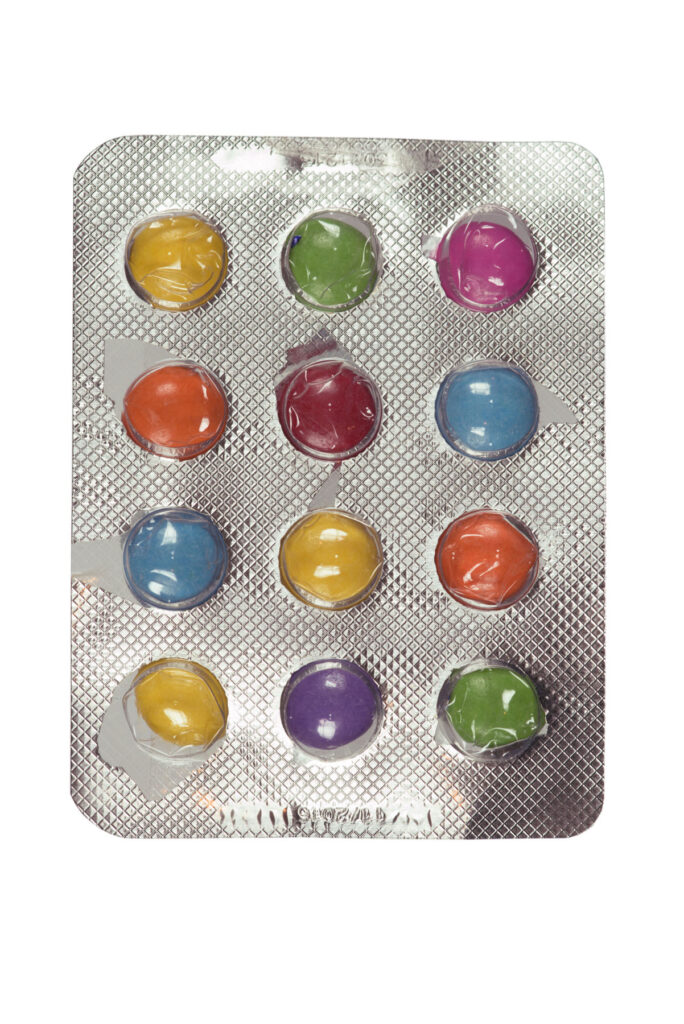

For my bachelor’s thesis, I wrote about how we all see colours differently due to genetic variations in our cones (which are the receptors that senses the light spectrum’s wavelengths in our eyes). I had this idea because I always subconsciously end up choosing colours from the same colour spectrum for my artworks, whereas other artists seem to use a different colour spectrum that is unique to their own work. I thought we might see colours a bit different for this reason, and it turns out we actually do. For my master’s thesis I will be writing about genetic traits and links between the mind of creatives and the mind of people diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. It might be that cliché of genius and ‘madness’ being connected, but when I was interning at a psychiatric department, it was really interesting talking to people diagnosed with schizophrenia, as;

“I felt that the difference between an artist making up their own universe for their work is not that far removed from someone living with schizophrenia experiencing their own surreal world.”

This is not to romanticise mental disorders or describe artistic minds as something pathological, but rather a better understanding of the links and differences between the two. It could possibly help people with mental disorders get better diagnoses and treatment.

The female form and nudity seem to be important concepts that you explore with your work. What are your thoughts on the relationship between the body and identity?

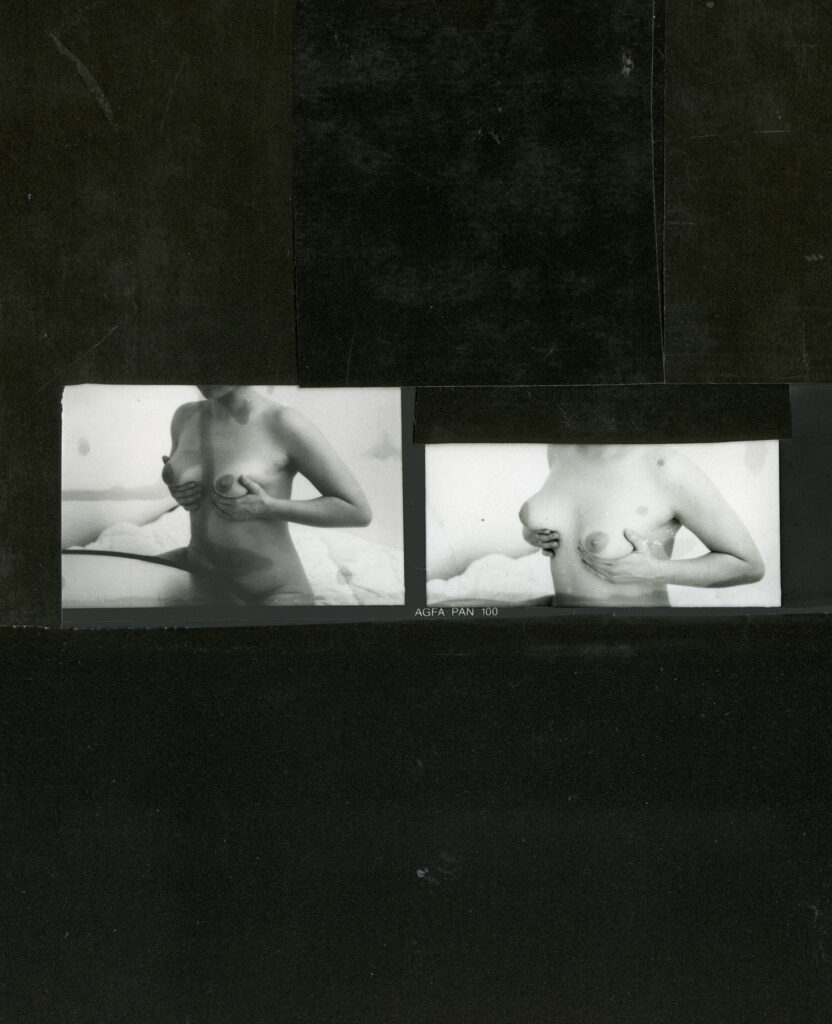

My series ‘Feminine Development’ addresses the alienation of the female body and female sexual identity, which has often been distorted by society. With cosmetic surgery and genetic manipulation, almost anything becomes possible in the strive of fulfilling society’s expectations of beauty and perfection. Using mirrors to manipulate the body in this series serves to illustrate how we’re slowly moving away from reality and merging with a surreal, parallel world where it is questionable what a natural body looks like. Creating the series, I confronted my own body insecurities by creating images that would celebrate the female body for its capability of giving birth and creating a child, starting from the division of just two cells.

I think the body and identity are two things that are inseparable. When you look at yourself in the mirror you identify as yourself. I think the way we talk to ourselves and the way we view our own bodies has a huge impact on our self-image and identity.

Do you aim to draw specific qualities out of the subjects of your photographs, or is it more a case of you wanting to capture something that is already present?

It really depends on the person who is being photographed and what they give me to work with. Some people have a natural talent for performing and expressing themselves artistically as models. For others, I give them more directions, but most of my models perform like actors in my surreal universe of images. Emotions are real and pure, but good actors are also able to show this.

I’m beyond thankful to all the people who have ever posed for me and trusted my vision and weird ideas. Most of them are my friends or family, so it’s a personal experience working with and portraying these people.

Do you have any rituals or habits that help to motivate you creatively?

Most ideas come to me naturally and without even knowing where they’ve come from, but a great catalyst for bringing my ideas to life is probably going for a run. Running helps open my mind so my thoughts can wander freely to form a new creative input. When creating new work, I usually have a vague idea in mind of what I want to capture. I bring the model, the props and go to a location usually outside in a park or field. The weather is very important as well, as I almost always shoot outdoors with strong sunlight and a blue sky – that’s when the colours appear most vibrantly and beautifully to me. What happens in front of the camera is determined by my mood, the mood of the model, and sometimes just by accident. When creating the images, I lose all sense of time and basic needs. It’s magical to be in this state of mind, but I’m physically and mentally very drained when I’m done with a shoot, so I need to rest before coming back to do another one. Reading, studying and being with people I love also recharges my batteries.

Where do you see your practice heading?

Recently I’ve been interested in the moving image, and I’ve been experimenting with making art and fashion movies. I would like to continue in this direction and create works that are on the border of moving image and still photography as a kind of living photograph, as well as making short films. Moving image is a whole new world to me and I’d love to explore these possibilities further.

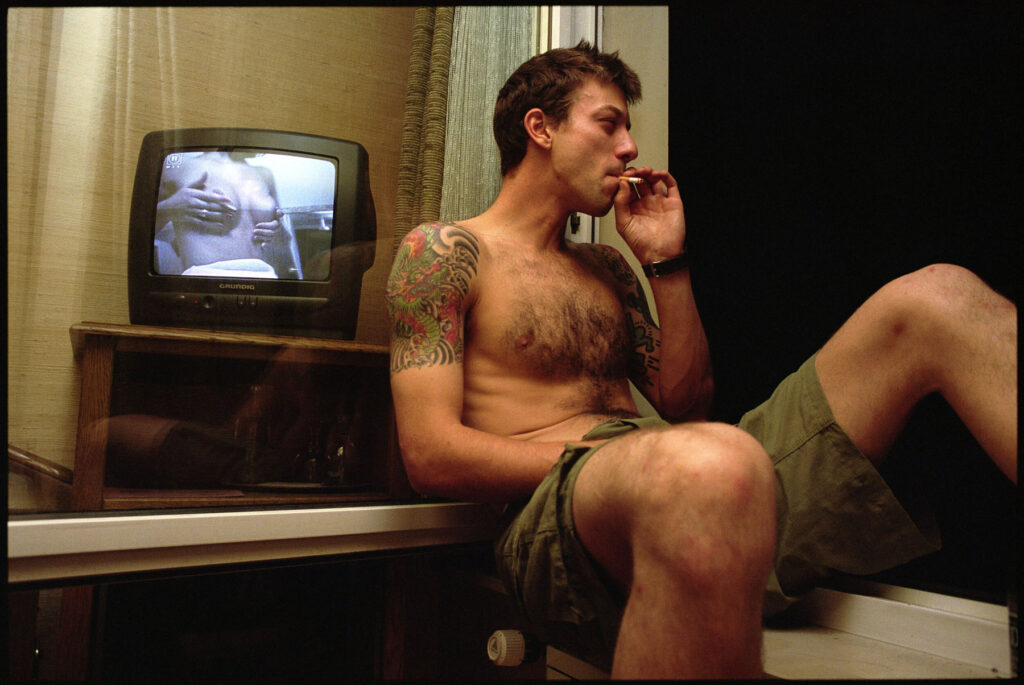

My new series of male nudes called ‘Modern Masculinity’ is also taking shape at the moment. I think it’s interesting to work with the male body and see what happens when I mix masculine bodies into my feminine universe. My goal is to portray the men as soft and gentle and to show another side of the masculine.

Credits

Images · HENRIETTE SABBROE EBBESEN

www.henrietteebbesen.com