An artistic metaphysical surgeon

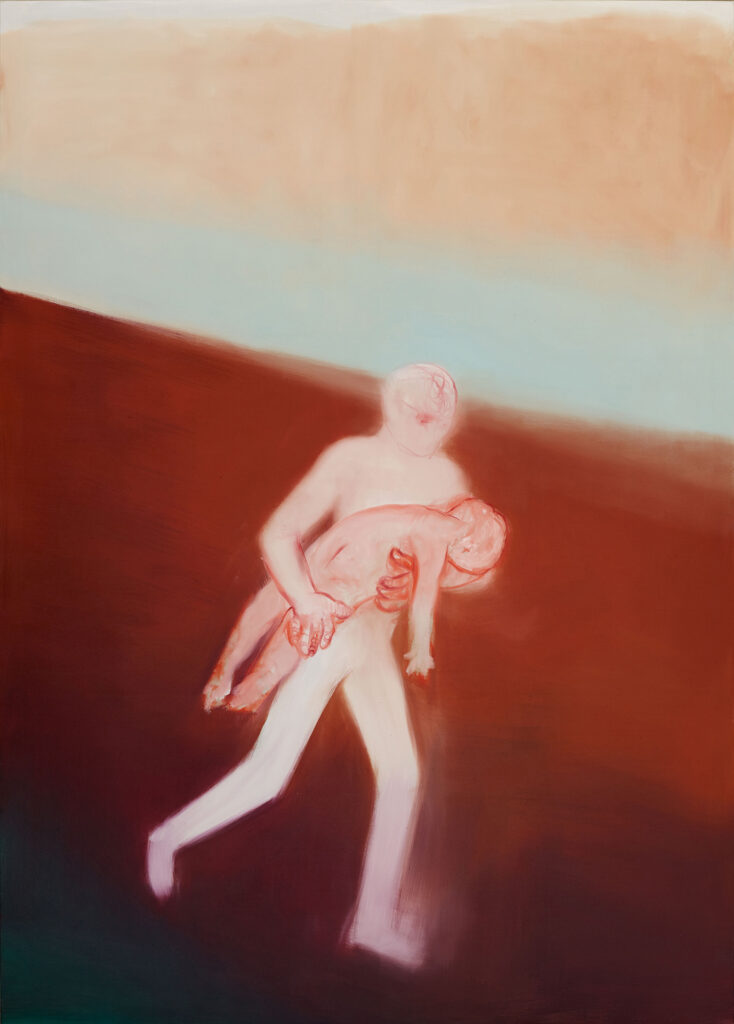

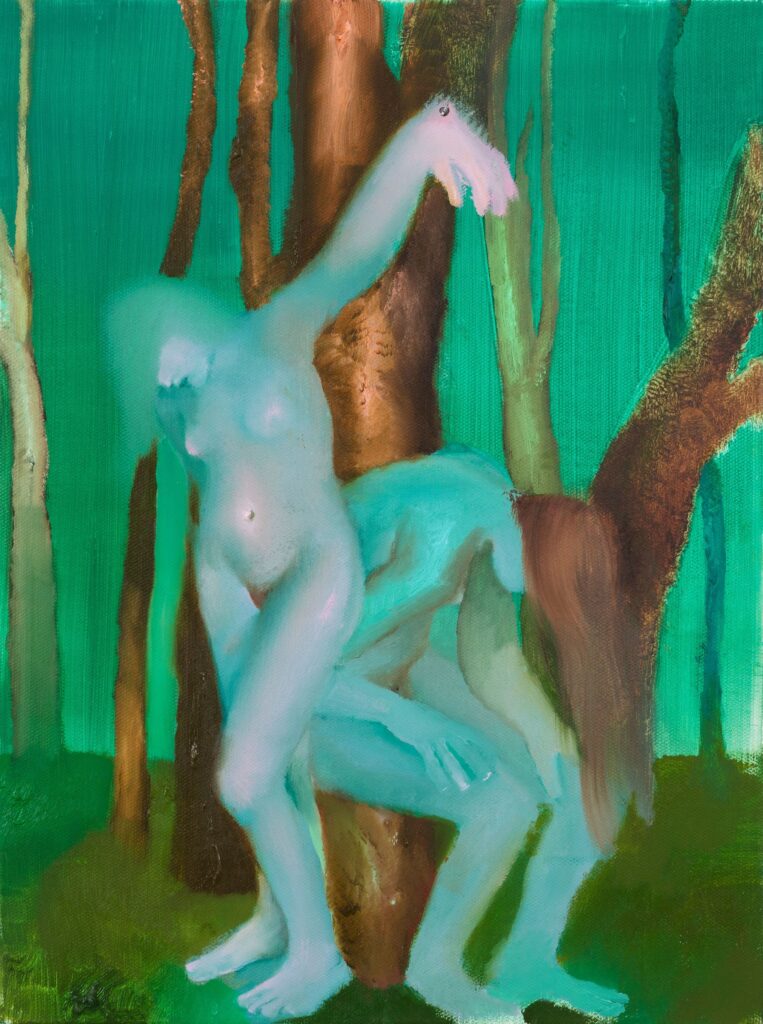

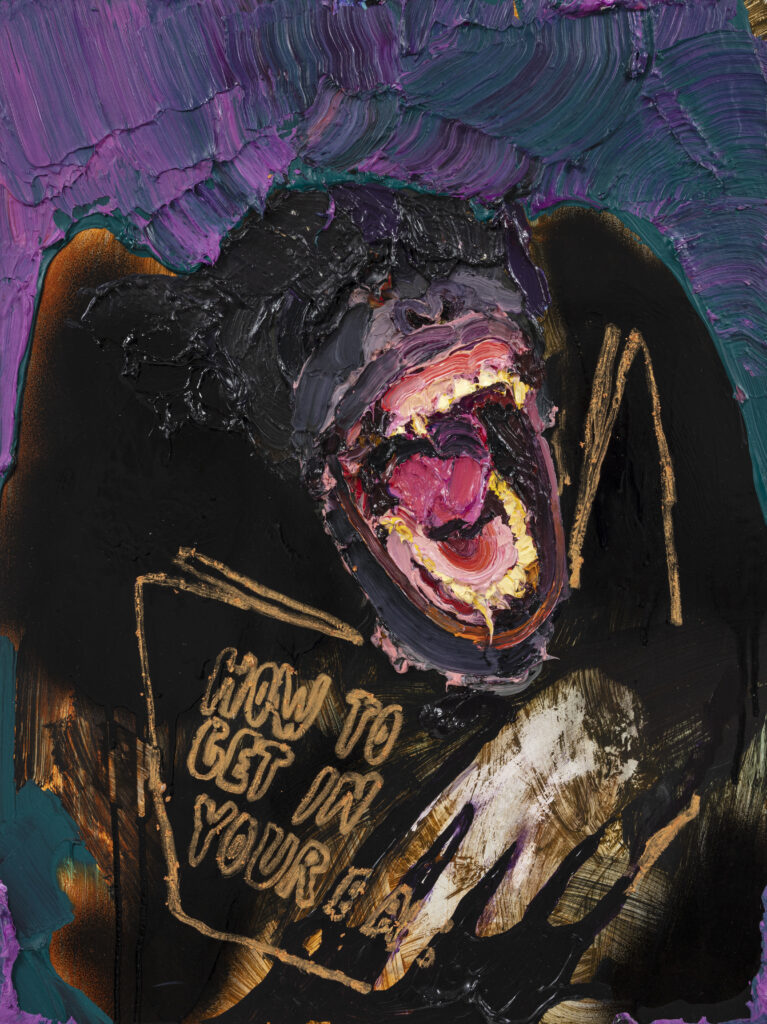

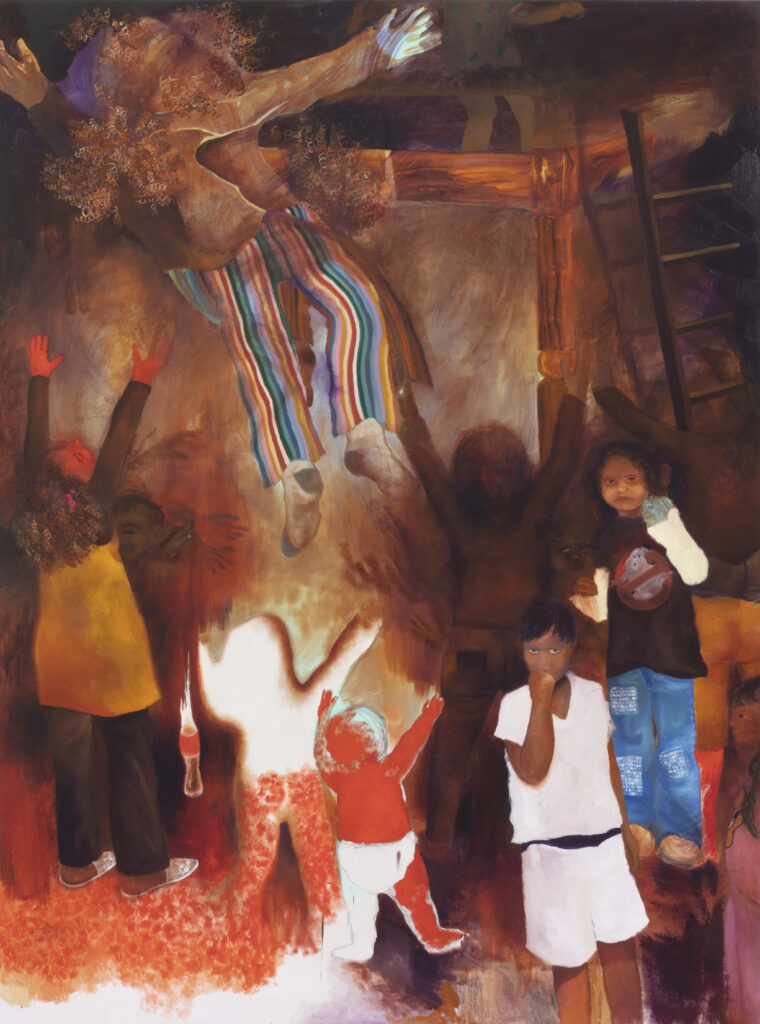

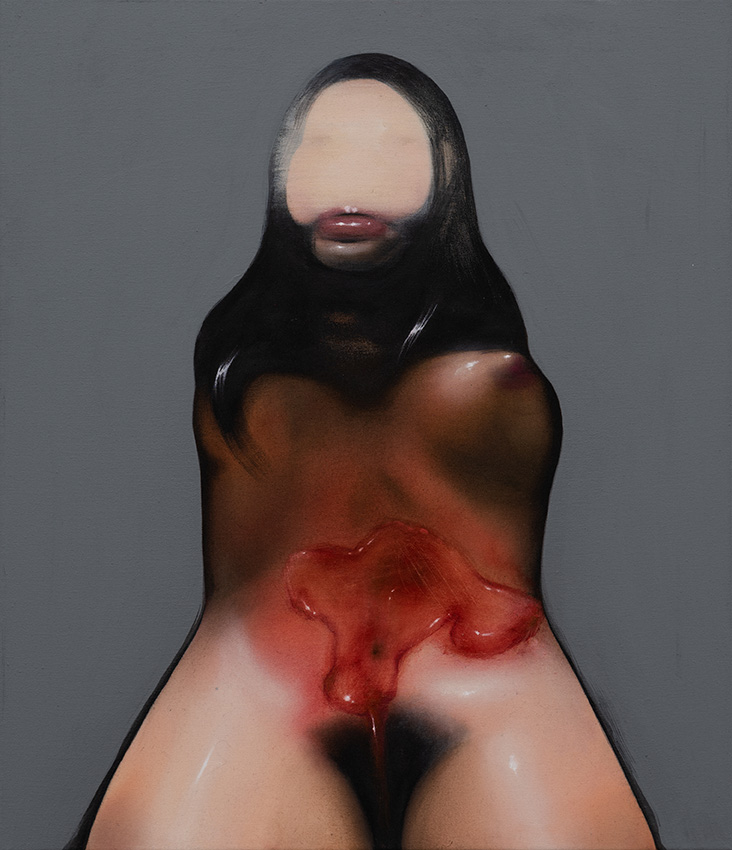

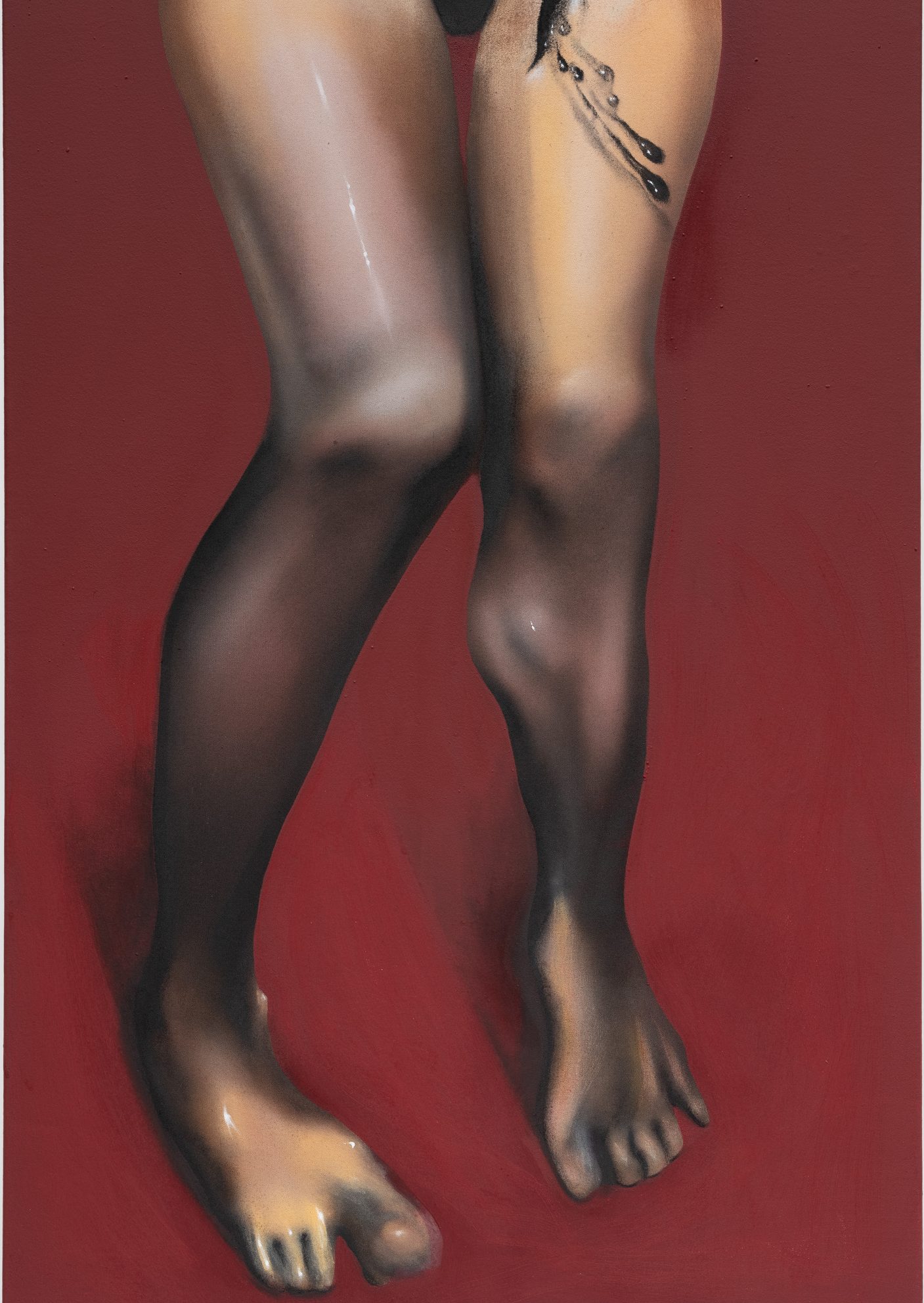

Grotesque bodies writhing in pain, catharsis, and even brief relief emerge in the artworks of Elsa Rouy. She is fascinated by the way bodies behave as vessels as if the form humans inhabit were once empty containers now filled with external impurities. In her paintings, the young British artist dissects women figuratively and literally. Blood and flesh intertwine, and their vivid shock and detailed stupor are brought out by every brush stroke. Eyes far apart, wet hair, dripping fluids, a cut-up chest, an eye coming out of the labia, entangled bodies, and complex, undefined, and intricate emotions to be unpacked and explored. These paintings unravel the mystic center of all kinds of emotions, anatomizing them until their influential power and how they come to play in daily life seep through and become known.

Elsa’s themed focus undulates too. There is an evolution in how she approaches her art, and it is evident in her recent paintings and their more pronounced technical elements. Her earlier works ooze abstraction with enough visual cues to pinpoint who the figures are (take her mother and child series where, for example, she explored the concept of bodily fluids and motherhood). Recently, her paintings take a darker route, a sharper solid state, and a more emblematic yet relatable spin on emotions. A temporary shying away from the diaphanous bodies of women, her artworks employ female forms as a medium of absurdity that hopes to make viewers feel unsettled. A gnawing feeling digs into their emotions as they gaze at the paintings, trying to pull themselves away from her artworks yet already too deep into Elsa’s world for them to let go.

In a conversation with NR, Elsa revisits the themes she explores, attempts to define the abstruse emotions that flow from her to her artworks, and reflects on her paintings as a gateway to who she is; the “metaphysical surgeon” moniker someone calls her; and the parts of herself she is still yet to unravel.

Matthew Burgos: I want to start our conversation from the beginning. Can you tell me about your introduction to the art world, paintings in general, and any personal experiences that made an impact on your artistic journey?

Elsa Rouy: I’ve always been into art, and it’s something I’ve done since I was a child. It makes sense for the trajectory of pursuing it as a career as an adult. There have been a couple of times that changed my view on how I approach art. When I went to college, I started seeing it as both a career and a hobby. This perspective became stronger in university. Thematically, my artwork is a development from childhood. I’ve always channeled my emotional experiences into a creative process, mainly through drawing and writing since I was a child. As I’ve grown older, this has become more prominent, extending into poetry and painting, exploring other art forms. Now, I’m working on this idea, but with the awareness to critically engage with concepts and consider their reaction to an audience rather than just myself.

Matthew Burgos: Would you say you grew up in an artistic environment?

Elsa Rouy: Yes, it was definitely encouraged. I think my parents weren’t artists or involved in the arts, but my mom used to draw sometimes, and whenever we did something creative, we were always encouraged to make things and draw. Doing anything with our hands was never discouraged. So I think it was a healthy environment where we were allowed to grow artistically.

Matthew Burgos: Were you conscious of the themes that you wanted to explore in your artworks?

Elsa Rouy: No, I don’t. I’ve always liked drawing the body, but I think it was only recently that I started to think deeply about it. It developed through my studies, but it’s only been in the last year that I’ve honed in on what I want to explore with my artwork and try to do that with precision, rather than just painting whatever comes to my head.

Matthew Burgos: But did you go through that process? Did you experience a time when you dabbled in so many themes, trying to figure out what you wanted to focus on?

Elsa Rouy: Yes – I think this happens a lot with everyone where you go off on different routes. There were definitely points where I was trying to make more explicitly political artworks or ones that were less overtly sexual, and maybe more about the ordinary, but I realized that I was interested in this idea of using the body as a vessel and manipulating it to express emotions and explore the brutality of the human condition. So, that’s what I want to focus on rather than trying to go down these other routes.

Matthew Burgos: Do you think there’s a spiritual context going on with this artistic thought?

Elsa Rouy: I guess so. I’ve never thought of it as spirituality, but I guess it could be in a way because I’m looking into emotions, and there’s a lot to do with, as I always said, about the body being this vessel, this container, and the idea of having these emotions and the existence that we have within it, the containment, and then the leaking out of it, and how we try to contain everything emotionally, but it doesn’t work. And that’s why I’m interested in the fluids coming out and the breaking of the body to signify this false sense of containment that we try to have. So I guess it could be spiritual in that sense, but I don’t think I do stuff for very spiritual reasons.

Matthew Burgos: What are these emotions that we’re talking about?

Elsa Rouy: It’s quite difficult to explain. So it’s not one emotion. It’s trying to look at the intensity of different emotions. They could be like despair or destructive emotions, or maybe even softer emotions like happiness. But then it’s taking them to the limit of complete chaos, basically. And I think a lot of the time inside, it can feel like that, and it’s trying to find the balance between the soft emotions and the brutal emotions. It’s hard to pinpoint which ones because it’s a different range. I guess they used to look a lot at shame, but I’ve moved away from that now, and it’s more of an exploration of different emotions.

Matthew Burgos: Are these emotions that you personally firsthand experience, or ones that you want to focus on in your art?

Elsa Rouy: I think it’s a bit of both. So it’s going back to what I said at the beginning where a lot of it’s taken from emotions that I feel. Then I write poetry, and it would normally be in the moment, get a couple of sentences out. And it’s the same when I come up with an idea for a painting. This image will start forming, but then I go back to them and from a non-emotional point or mindset, I change them. So it’s more like observing the emotions from a distance rather than them being chaotic.

Matthew Burgos: You’ve mentioned before that your works are a visual portrayal of mixed emotions, very complicated and hard to define. But at the same time, you set boundaries between you and your work because, at the end of the day, you’re not your work. But you also added that self-reflection is part of your work and that painting allows you to reflect on your emotions. When does this process of using paintings as your medium start and end, and how do you separate yourself from your art?

Elsa Rouy: I think when I said that I’m not my artwork, I meant it in a quite literal way. When I get criticisms or if I get frustrated with an artwork, I don’t see the artwork as myself, and I try not to let it affect me so directly. It’s not like somebody is attacking me as a person if something goes wrong with the painting or if somebody doesn’t like it or gives a critique. I don’t take it as a personal attack. But I think with the actual artwork itself and myself, it’s a blurred line. And I don’t think there’s ever a clear separation. It’s difficult because when you do it every day and you’re constantly thinking about it, it kind of becomes part of yourself.

I was thinking about this question earlier when you asked me, and the best way I can describe it, it may sound pretentious, but it’s like myself and my artwork seem holistic. All the artworks that I’ve made before and the ones I’m making, as well as the ones in the future, seem to already exist in my head as a space, but not physically. So I think there is a detachment from the physical artworks, but the creative process, the ideas, and the concepts that form them are very ingrained in me. They’re constantly there, and I’m constantly picking them in my head, trying to figure out what I want to do, referencing what I want in the future with my artwork, or what I want in the past and trying to make that now. It’s like they coexist in a plane, and they’re webbed together. There’s probably no escaping being fused with my artwork now, but on a mental level, not physical.

Matthew Burgos: Do you continue the themes that you worked on in the past, or do you prefer to explore new ones and inject nuances of the past themes?

Elsa Rouy: It depends on the theme. Some are recurring, which is natural in my practice and life. But I also leave behind themes that no longer feel important or have reached their limit in exploration. However, even the themes I leave behind still inform the ones I want to explore now. For example, I used to focus on grotesque women and their bodies, but now I use the female form to create absurdity and make people uncomfortable in a different way. So there’s an evolution in how I approach certain themes.

Matthew Burgos: I came across your series where you conceived artworks related to bodily fluids and mothers, and looking at these paintings, how did you correlate these two?

Elsa Rouy: The first theme I explored was about containment and expulsion of the body. Initially, I focused on bodily fluids explosively leaving the body, but now I examine them as leaking or coming out. Whereas before, it was more like violent explosions. Pregnancy and giving birth represent a similar idea, with the body as a container releasing something in a chaotic and violent manner. Both themes touch on the delicate balance between life and death. The expulsion of body fluids can signify dying or illness, while giving birth is about bringing life into the world but also carries risks of death and health issues. To me, these themes have similar meanings as images. The mother figure was significant because it relates to a personal aspect. I used to have fears about becoming a mother, but I’ve now overcome them. When I painted these images, it was like a weird compulsive thing to shift this idea.

Matthew Burgos: What qualities come to your mind when you think of the words mother and child?

Elsa Rouy: The qualities I explore in my artwork related to the mother and child theme are both self-evident and multifaceted. On one hand, it’s about ideas of nurture and protection, creating a safe environment for growth and survival. However, I also delve deeper into the notion of the mother as a safe space while the baby represents something strange and potentially scary that the mother may reject. It’s about examining these complex dynamics.

As for the child, I see them as innocent, fresh, and malleable. They embody a sense of purity as they haven’t been influenced by external factors yet. At that stage, they just exist as a being, growing and learning without the complexities of language and cognitive processes. It’s like witnessing the pure essence of human existence before the complexities of life come into play.

Matthew Burgos: Can you describe your relationship with your mother?

Elsa Rouy: We’re very close, and I consider her one of my best friends! She’s actually visiting me at the moment.

Matthew Burgos: That’s great to hear! And about your recent artworks, you depict a lot of transfigured feminine bodies that exude a wide range of emotions. It made me wonder if these paintings portray psychological dilemmas or distress experienced by the subjects, and if the use of body and nudity serves as a medium to express these emotions. Could you provide some insight into the world that inspired you to create these images? What kind of environment did you immerse yourself in, and what did you envision while visualizing these artworks?

Elsa Rouy: Yes, my recent artworks explore points of emotional brutality. I use the body as a vessel and manipulate and distort it, completely objectifying it until it becomes uncanny and uncomfortable. This allows it to express intense and palpable emotions. I set up scenes with doll-like figures to awkwardly express these feelings. I prefer the snapshots of moments in the paintings because I’m fascinated by the spaces in between things. The slightly abstracted, broken, and distorted bodies create tension, leaving gaps for the audience to interpret and create narratives in their minds. There’s no predefined narrative; the bodies are like puppets placed in a scenery for the audience. The distressed and distorted faces evoke personal emotions in people, making them feel connected and touched. It’s interesting to use the body in a cruel and brutal way to bring out vulnerable and soft emotions in ourselves.

Matthew Burgos: And you did quite visually and literally dissected the body in one of your paintings. Was it a way for you to metaphorically look into the person or explore who that person is?

Elsa Rouy: Yeah, I think so. The figures are all somewhat based on me, so it’s like breaking the person to find what’s inside. Someone recently described me as a metaphysical surgeon, and I thought it was funny and accurate. It’s weird, but that’s kind of what I do. I never thought of it that way before, but it makes sense. I liked that idea. I’m like, “This is great. I’m going to run with this.” Especially because I want to explore more about blood and the concept of small cuts on the body. It fits well with these ideas. But yeah, it was funny.

Matthew Burgos: I’m wondering if you like horror and gory movies?

Elsa Rouy: If it’s done well, yes, but I like more stylistic ones. I’m not the biggest fan of slasher movies, but I like ones that are more campy eighties ones with the prosthetics and all of that. I went to see Men (2022) with my friends at the cinema, and there’s this scene of a weird rebirth from a man’s body, with grown men coming out of a vagina and everything. And as soon as it happened, all of my friends at the cinema looked at me. I sort of liked that part – the scene, I mean.

Matthew Burgos: Are there things about yourself that you want to know and/or learn more about?

Elsa Rouy: I want to explore everything! I want to discover new things that I genuinely enjoy and are exciting. There are so many activities and experiences I haven’t tried yet, and I believe they could bring a lot of joy into my life. So, I’m eager to find out what I truly like and expand my horizons. I’m interested in getting back into dancing. I used to do it when I was younger, but now maybe try a different style. Um, on the other hand, gardening seems intriguing. Whenever I see videos of it, it looks so calm and relaxing. I’ve never tried it, but it seems like a nice activity to explore.

Matthew Burgos: Even if you have a lot of things to explore, a lot of things that you want to learn more, do you feel connected to yourself or do you feel like you have to learn more about who you are?

Elsa Rouy: Thinking about it now, there are times when I feel connected to myself, for sure. It fluctuates; sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t. I see it as a learning process, and it’s natural for it to go up and down throughout life, which makes it interesting. You think you know yourself, and then suddenly you realize that you don’t. It keeps life entertaining and exciting.

But I notice I feel very in touch with myself when I’m using my mind and body together, like when I’m painting. The cognitive movement of my body and the thoughts work in harmony, and in those moments, I feel like myself. On the other hand, there are times when I don’t have control over my body, like when I’m on my period or when I’m ill. In those moments, I feel grounded and deeply connected to my humanity and my body. My brain isn’t preoccupied with self-concepts; it’s more focused on the physicality of the body. And I think that’s when I feel most connected to myself.

Matthew Burgos: And how do you feel today?

Elsa Rouy: I feel pretty good actually. No crazy emotions going on today, but who knows – it could be different tomorrow.

Credits

A FACE WHEN LOVED, 2023

DANCING ON BROKEN ANKLES, 2023

Artworks courtesy of the artist.