For those who may still not know you, would you like to tell us a bit more about the brand and how you started your career as a fashion designer?

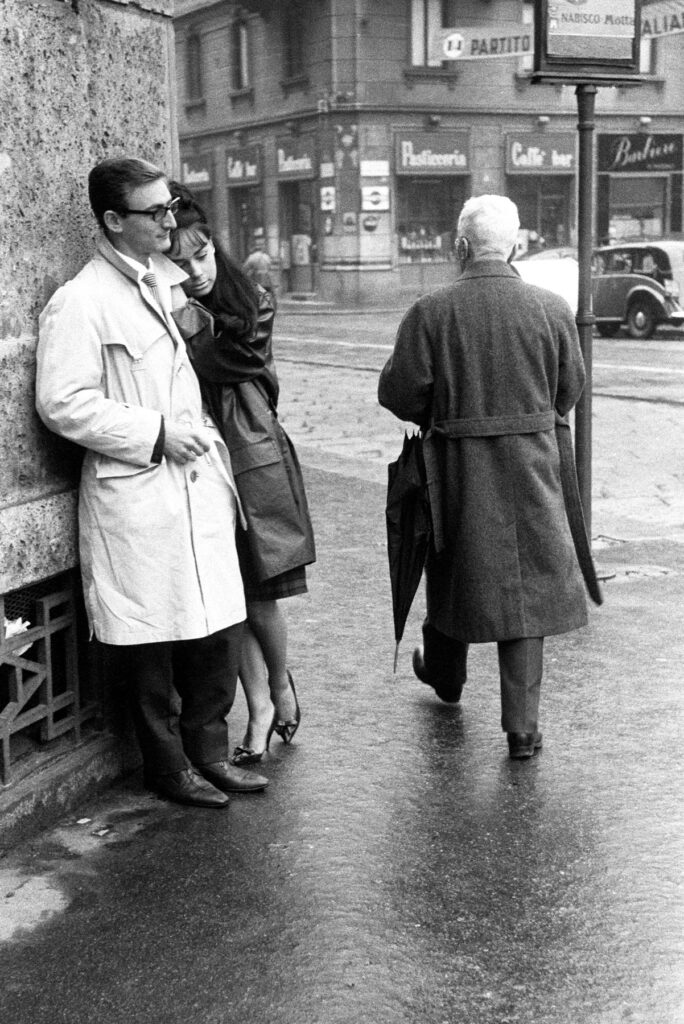

I grew up in Greece, around my grandmother who ran her own tailoring school, and this is where I learnt to sew and construct a dress from a very young age. I think this experience has influenced the way I see fashion in general, from the point of view as a seamstress who works with her personal clients, rather than its normative context. I admired her deep connection with her clients. While the fabric was pinned to the body there were secrets, tears, laughter… I craved this deep intimacy between the designer and wearer, which I first got to experience while developing my final collection at Central Saint Martins. My models would run around the studio naked, share personal stories, and discuss philosophy to help with the design development. One moment we were laughing, the next one crying: I fell in love with that process of design, an exercise based on personal experience and interaction.

How has your brand developed since your graduation at Central Saint Martins back in 2018?

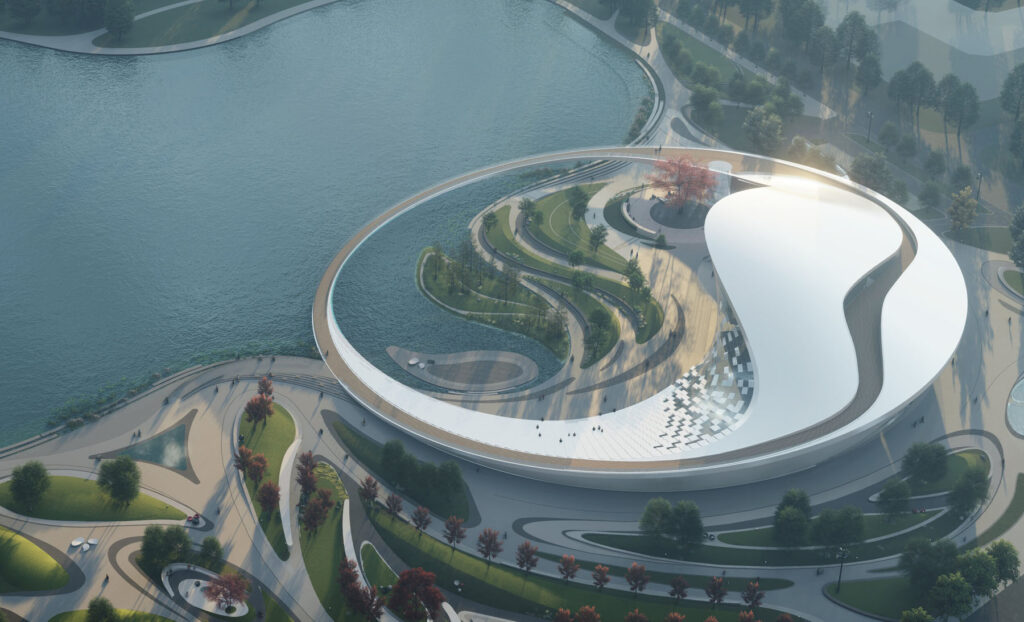

The ethos of our brand is centred around the ‘Wetness Theory’. It has remained the same, and continues to be a focal point of our design inspiration. Each collection explores this through new viewpoints: looking at the evolution of the journey of a woman, her relationship with water, and how she is becoming more accepting of her bodily waters.

For the SS21 collection, titled Self-Birth, water is examined as a vital force of life, and re-birth, that allows introspection, and ultimately self-reconnaissance. With a focus on Maternal waters, and the journey to self-healing, the film displays the vision of a woman floating on water, representing the act of transcending – an ecstatic self-birth.

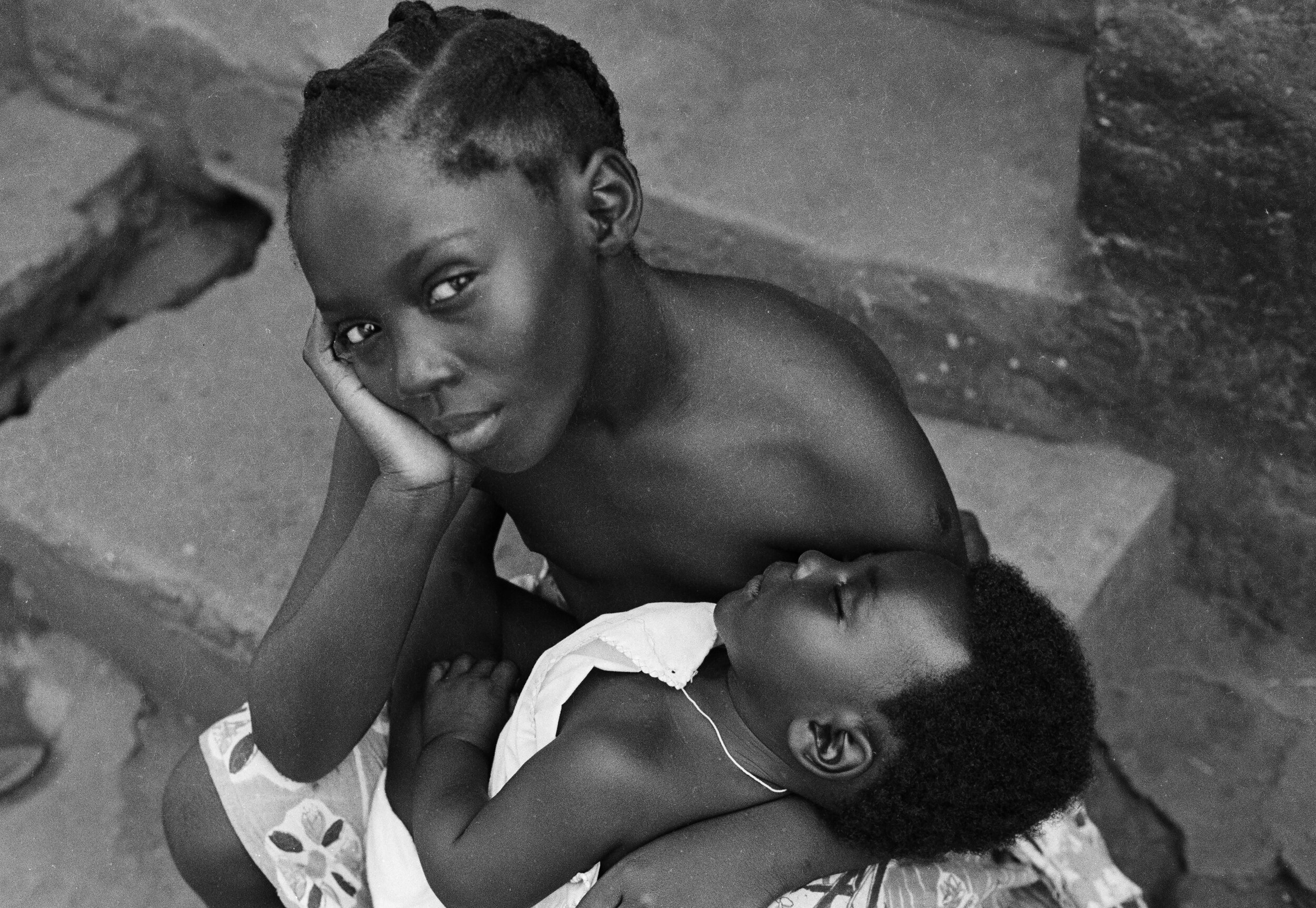

Our AW21 collection, titled “I am my own Mother”, is inspired by the devotion of self-mothering. To love one-self unconditionally, embracing the strength that comes with self-acceptance of our Bodily Fluids: Water filtered through our bodies, Bodily Water. Holy Water, Sea Water. After last season’s collection centered on ecstatic birth, we now look to a transformative future, harnessing the power of self-love for unashamed self-expression, with the aim of strengthening the connection to our physical and immaterial self, water.

How do your origins inform your work?

To me, the sea has played an essential role in growing up. My hometown in Greece is next to a harbor, meaning I could always hear boats leaving the docks from my bedroom. I find sea healing: to me it feels like home, it has played a big part in my research and creative practice with the DI PETSA brand.

In terms of cultural influence, I am very interested in exploring antiquity, how it coexists in contemporary culture, and how we communicate our relationship with the past in general. Greek mythology and practice inform my designs. For SS21, we developed a golden prayer corset that’s entirely hand-embroidered with materials traditionally used in Greek orthodox priest-wear.

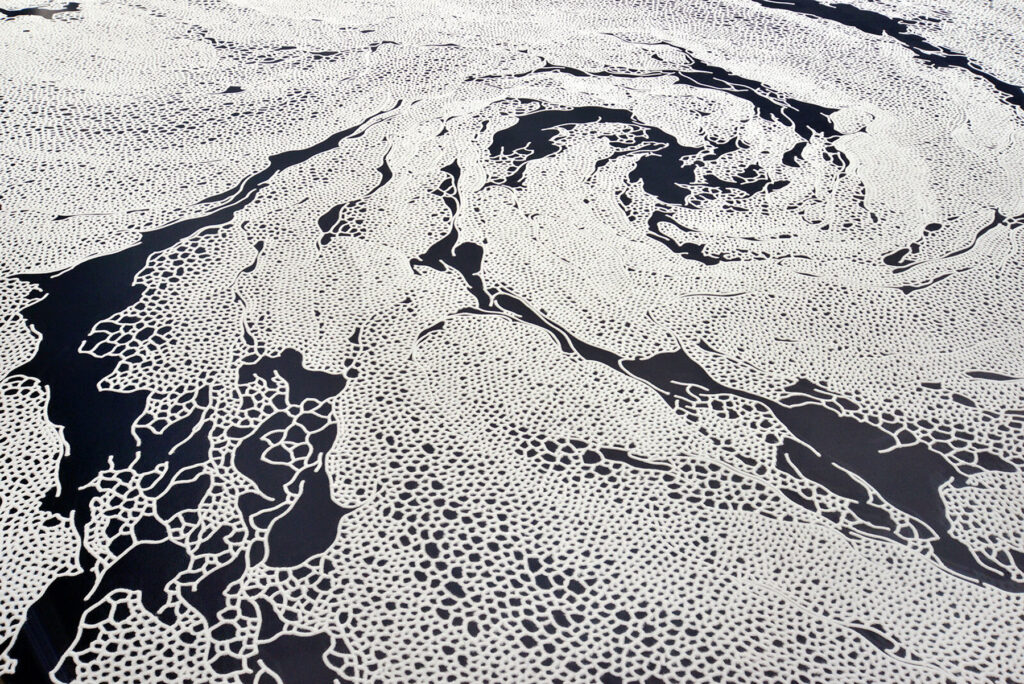

Lastly, craftsmanship, sustainability and textile innovation are very important to me. I am very moved by the dying art of traditional greek craftsmanship. I would love to find a way to preserve it, to interact with it in my designs. For our latest AW21 Collection we have been working with a local group of women in Athens – the Lyceum Club of Greek Women, an organisation founded in 1911 – who work towards preserving traditional arts, including embroidery and lace making. For our latest season, we created our first collaboration together. My long term aim is to be able to provide jobs for these women, to facilitate the training of younger people, in order to preserve such crafts in the future.

I see Di Petsa, I think WET DRESS. Can you tell us about the inspiration behind it?

The Wetness theory behind the brand evolved during my time at CSM. I was conducting eco-feminist research, investigating the relationship between Women and water, Women and their bodily fluids. The idea was to create a vision of a totally wet woman, fully accepting she is coming from water, and of her wetness. Our goal in fashion is to allow people to be unashamedly wet. To create beautiful work that can inspire others to consider nature as something of our own. Our bodily fluids. Water filtered through our bodies, bodily Water, holy Water.

The Wetlook comes after an original technique that took 6 months to develop during my master’s years at Central Saint Martins. Its conceptualization started from a series of performances I was doing for my BA years studying performance, design and practice. I had a woman dressed in water walk across Athens and that was the idea I wanted to crystallize: somebody wearing their own Wetlook could be part of this water performance without actually having to be wet.

Where does your work stand in relation to Feminism?

The brands Wetness theory seeks to subvert the idea of shame of natural bodily fluids. By re-narrating their physical and philosophical context – a notion that is unapologetically on display through our Wet Script Mesh collections, with poetic scripts, such as “Cries in Public”, “Holy Water, Sea Water”, “Wetness”, digitally printed onto the surface of the mesh garments – our mission aims to inspire the wearer and act as subtle reminders in the performance of their everyday life to embrace their wet self.

Through our work we aim to create a new narrative around bodily fluids and the female body, a subject that often remains taboo in mainstream media. We want to make women feel comfortable and empowered in their natural self, something which we are conditioned and told through the media to change and mould into what society views as the “ideal” vision of a woman. It feels very sanitized and stirpped back, “if you cry in public, you must hide it, if you breastfeed in public, you must hide it”.. There is a censorship of our bodily waters: the fact that we are wet, the fact that we come from water is something to be hidden. Shame is a self-inflicting punishment. This research, which has resonated with a lot of other people, is to this day a personal healing journey.

Your work also penetrates the realm of performance, how does such practice enable you to spread your voice?

I knew I loved fashion, but I was also very interested in performance art, theater and film, and I wanted to acquire skilIs that would develop my artistic practice and bring new viewpoints and inspiration to my fashion education. I did my first degree in Performance Design and Practice at Central Saint Martins. When I graduated I continued onto the Masters in Fashion Design Womenswear, and that was where I really combined all my skills and interests into one practice: couture fashion practices, textile development with performance, sustainability and film.

Both performance and art are so important to my work and creative practice. I am very involved in my work: it is something very personal to me. The relationship between model, designer and viewer is very interconnected, that’s why I always take part amongst the performers in my shows, exploring my vulnerability and body expression, alongside their exploration. Through these intimate moments, and the overcoming of shame, I can really tap into my creative side, and create work that comes from a deeper place. Work that is authentic to me and my experience. For us, a garment worn with intention and connection to a deeper emotional message, is one that will resonate and last with the consumer.

At DI PETSA, we are working on many different creative projects aside from the RTW collections. We recently launched a book, titled WETNESS: A Script of bodily Fluids, which I wrote and also illustrated. The book consists of 7 chapters exploring 7 bodily fluids: Saliva, Tears, Breast Milk, Vaginal Fluids and Semen, Sweat, Blood, and Urine. The writing is a merge of scripts for a filmed performance and poetic text which aims to create an alternative narrative for bodily fluids.The book includes direction notes, rehearsal exercises, diary logs, and fashion illustrations offering a behind the scenes eye to the Wetness concept and the performance work at DI PETSA.

We also run monthly Wetness Workshops that allow our audience to deepen their connection to water at large, and the connection to our bodily waters.