“In making the work I make I am lifting up my ancestors and their stories and learning more from them every day”

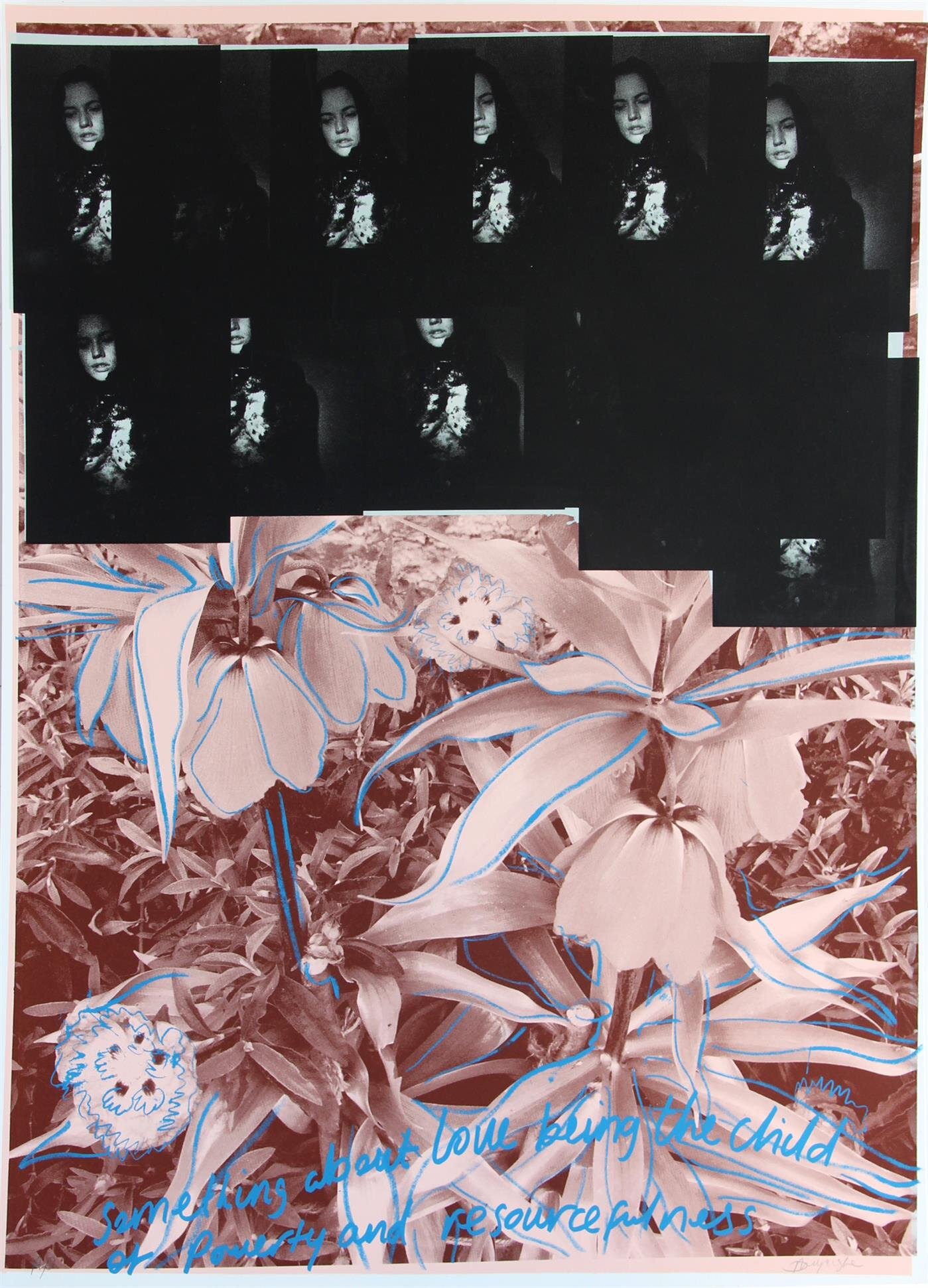

Judy Watson is an Australian artist whose practice is based on her exploration of her matrilineal Waanyi Aboriginal heritage and the experiences of Aboriginal people since British colonisation. Exploring Waanyi culture through the lens of collective memory, she then incorporates these histories into her artworks, often drawing on archival research and documents.

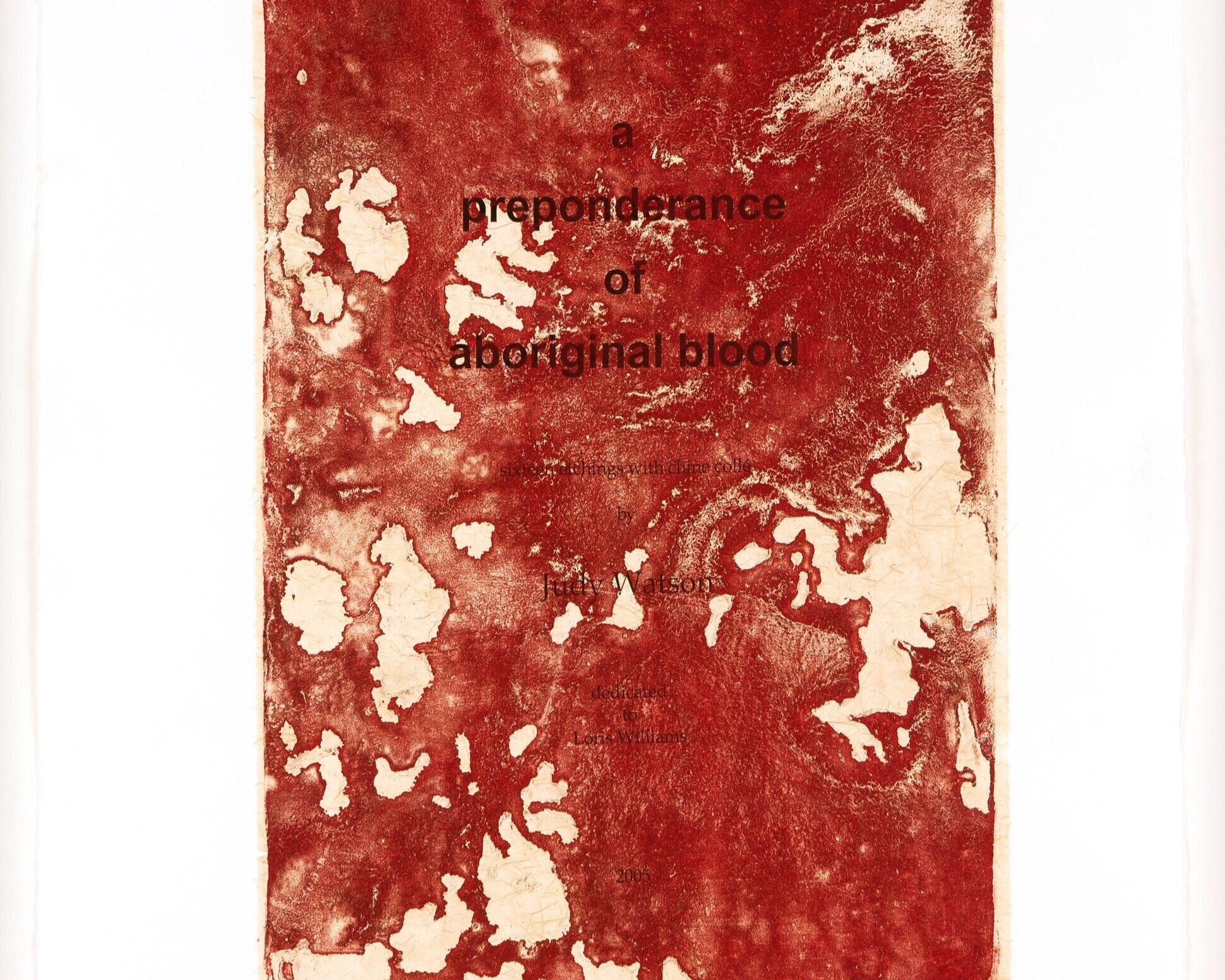

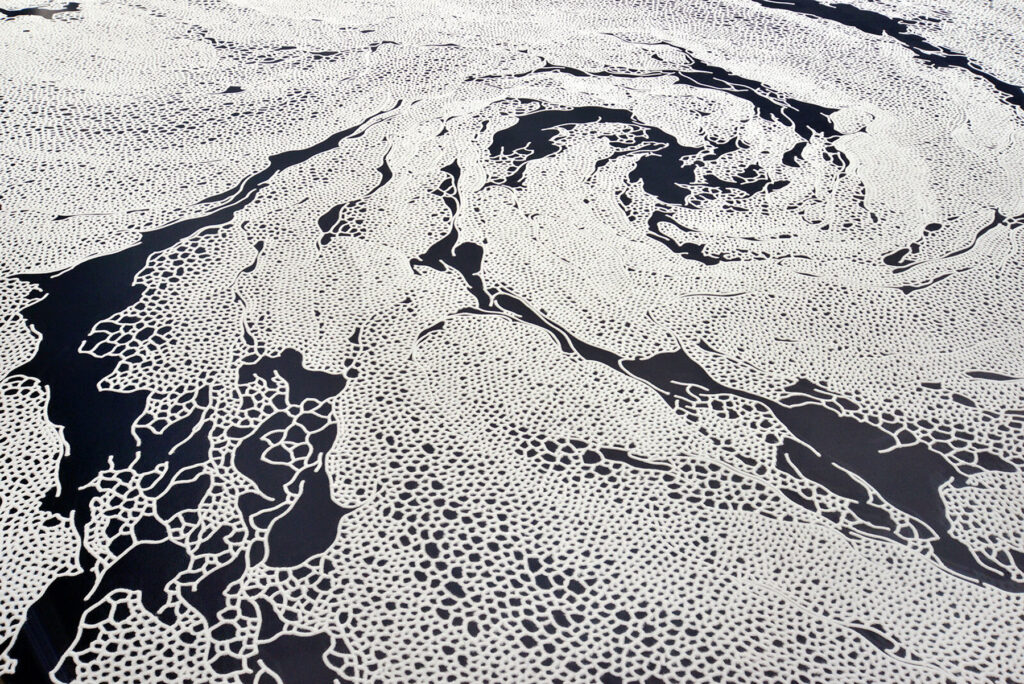

Watson’s work a preponderance of aboriginal blood uses copies of documents from the Queensland State Archives which are then layered with ‘blood-like pools of red paint, symbolising the pain and deaths of Aboriginal people.’ The documents in question are evidence of the discrimination Aboriginal Australians faced, including voting rights.’Full blooded’ Aboriginal people were not allowed to vote but ‘half caste’ Aboriginal people were. The artwork highlights the awful treatment of Aboriginal peoples in Queensland as a reflection of the ongoing effects of British colonisation.

This artwork will be part of A Year in Art: Australia 1992, a free exhibition at Tate Modern. The exhibition brings together a selection of over 25 works, many on show for the first time in the UK. The exhibition explores how artists have acknowledged the continuing relationship Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have with their lands, as well as the ongoing impact of colonisation and the complexities of representation in Australian society today. The exhibition is available to view from June 8th 2021 until Spring 2022.

When it comes to ideas of social change you have described your work as subtlety discreet with a strong message that insinuates itself into the viewer’s consciousness, do you think that aesthetically pleasing and subtle artworks can be used as an effective form of activism?

Yes, I think the power of aesthetics and subtlety can embed themselves into people’s memory and slowly leak their contents into their consciousness before they can put up resistance. Sound and smell can be a strong activation as well.

Do you think this exhibition, and your artwork specifically, will make British people more aware of the issues of British colonialism and how that affected/affects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders?

Yes, if people look into the work, they will get a sense of the oppression of Aboriginal people under the ‘Act’.

You talk about collaborating with family members on your artworks. Did they have any specific input/influence on a preponderance of aboriginal blood, and if so in what way?

I spoke to my mother, Joyce Watson about this work. She is also trained in printmaking, in fact, I was one of her first art teachers at Art School in Townsville. After making this work I took Mum and Dad into the Queensland State Archives with me. I showed them the files held on my grandmother, Grace Isaacson (Camp) and her mother Mabel Daly, among other members of my matrilineal Aboriginal family. I made a second artist book: ‘under the act’ based on these files. My mother is very supportive of me using this material in order to show the public what it was like for our people to live their lives under this institutionalised brutality and bureaucracy. My grandmother, Grace Isaacson gave permission for us to access her files.

You speak about collective memories as an inspiration for your work, have you found that a lot of personal histories and information have been lost due to a fear of discrimination from British colonialism? And if so did you find that loss of personal histories frustrating when researching during your process?

Many people have helped me to uncover documents and history about my Aboriginal family. I did interviews with my grandmother Grace, my mother Joyce and other family members from Mt Isa over the years. I’ve also undertaken a lot of research as have others about these untold stories of colonisation in Australia. It was hard at first to find these stories but we achieved it with persistence and hard work. There is more to be unearthed in the future.

Can you tell me about your creative process for a preponderance of aboriginal blood? How did you come up with the idea and how did you go about the physical process of making the artwork?

I went to a talk by Loris Williams (an Aboriginal archivist) and Margaret Reid at the University of Queensland about Indigenous people and the right to vote in Queensland. They showed amazing documents on their PowerPoint and this is where I first heard the terms: half-blood and a preponderance of Aboriginal blood. Immediately I knew that this is what I wanted to make work about. I had been asked to make an artist book for the commemoration of Queensland women and the right to vote. I knew I wanted to focus on Aboriginal women in particular. I asked permission to use the images from Loris Williams’s talk and it went from there.

I’ve discussed the making of the work in previous texts that you can access from the description in ‘a preponderance of aboriginal blood’.

In previous works you have united your Aboriginal heritage with your English, Scottish and Irish ancestry such as standing stone, kangaroo grass, red and yellow ochre, is this also the case with a preponderance of aboriginal blood? How else do you navigate the contrast of these ancestries within your work?

My work ‘burnt shield’ which is in the collection of the Queensland Art Gallery could be the shape of a European family shield. It could also be the female shape of the pubic area, or the waterhole at Duwadari waterhole, Lawn Hill Gorge, Boodjamulla National Park in NW Queensland. Sometimes I have referenced my skin colour, derogatory names and imagery associated with flayed skins. These are earlier works, both in prints and works on canvas.

You stated that shared experiences are an important part of your work. How do you feel to be a part of this group exhibition and is there any other artists artwork that particularly resonates with or stands out to you?

There are many amazing artists whose works resonate with me.

Sometimes I know them and sometimes I don’t but their work goes beyond the knowing.

You describe discovering how your Aboriginal ancestors were treated as a ‘heavy burden’, do you consider your artistic work/process as a way to work through, express and deal with that ancestral trauma?

In making the work I make I am lifting up my ancestors and their stories and learning more from them every day. I want to pass that knowledge onto my children and to others in the wider community.

What other media (i.e. books, films, documentaries) would you personally recommend to people who are looking to learn about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures and the effects of British colonialism?

Tony Roberts ‘Frontier Justice’, Timothy Bottoms ‘Conspiracy of Silence’, Bruce Elder ‘Blood on the wattle’, Rachel Perkins ‘First Australians’. So many books, videos, resources…

What artworks are you currently working on and which topics do you plan on exploring in the future?

I am currently making two bodies of work for different projects and venues that I can’t reveal yet.

One project is looking at climate change. The other is looking at a big issue affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody. I am also working with more research around the Aboriginal women in my family, the stations they worked on, the maps of the country. Other imagery will appear as I go through the process of making the work.

My public artwork ‘bara’ will be installed soon at the Botanical Gardens in Sydney, looking down at the Opera House. It is a large work in marble that represents the bara / fish hooks made from shell. These were predominantly used by Aboriginal women in Warrane / Sydney when they were fishing in their Nawi / bark canoes in the waters around Sydney, catching fish for their families in Gadigal Country.

Credits