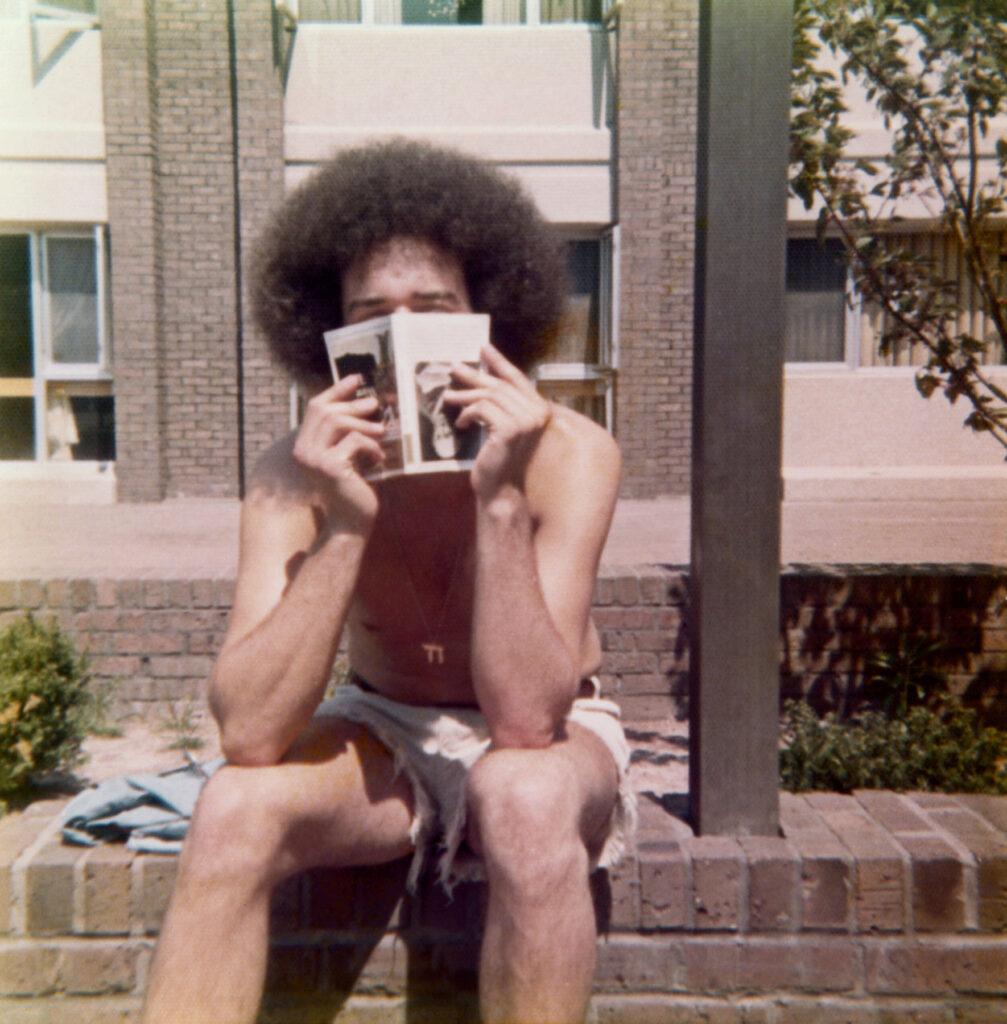

“Take a camera or computer and do things that motivate you. Do, do, do and do, that’s the way.”

A whale splashes about with its calf in a garden swimming pool, a speed boat spins in circles upon a galaxy of stars, and famous buildings just up and float away. These are just some of the worlds Argentine filmmaker Fernando Livschitz brings to life in his short films. “His stories unfold organically showing the extraordinary as something ordinary and common. Going deeper into reality through the wonder that is in it by creating a charming and mind-boggling mood.”

Indeed, his works are inherently surrealist by nature, incorporating the mundane with the absurd, but there is an inherent youthful playfulness to them that offsets their obvious technical conception. They invoke all the innocent creativity of a young child, who has been set loose in reality and has been given the power to make it their plaything. In doing so they remind us all of the freedom of childhood imagination, unconstrained by adult worries such as gravity or logic.

Livschiz’s films are viral by nature and have been seen by over a hundred million people. He has directed all over the world, winning The Young Directors Award at the Cannes Lions and worked with well-known brands including creating the opening credits for CBS’s The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

How long does it take for you to make each project/video and what’s your artistic process when coming up with ideas for your work?

It could take one day or months to make a project. there is no logic there.

Usually, I start from a small idea or concept I want to show and then the process can lead in other directions.

Which is your favourite project and why?

I’m not sure, maybe “Buenos Aires Inception Park”. This project is 10 years old, and it has opened all kind of doors in my career.

You stated that during lockdown you didn’t feel very positive because of the current situation, is that what inspired you to make Anywhere Can Happen, which is a very uplifting and positive work.

Well, I’m not sure if it was the lockdown period. Life is complicated beyond this crazy time. I feel we can see things as different, more positive.

Which was the most difficult project you worked on and how did you overcome the challenges you faced while making it?

Each project has its complications. When I start with a project I’m not sure how I’m going to do it. As I progress, I discover the complications. Sometimes I feel that my work is based on gradually solving the problems that arise.

Is there anyone/anything in particular that you draw inspiration from (ie, literature, films, artists, creators etc)

Yes, lot’s of artists: Slinkachu, Michel Gondry, David Lynch, Tim Burton, Leandro Erlich, Pablo Rochat, Fubiz, Vimeo Staff Picks, Nowness.

How do you think working on an international level affects the creation of your work?

I think it affects it in a positive way. The greater the knowledge, the greater the possibilities.

What advice would you give to young creatives looking to work in animation and film?

Do not wait for things to come from outside. Take a camera or computer and do things that motivate you. Do, do, do and do, that’s the way.

In the BTS of Lost in Motions, I saw your daughter helping you to spray paint the individual pieces you used to create the stop motion. Do you often include her in your creative process?

Yes!, she has an innocent view of things and life and I love her opinion. She has great ideas.

You have a background in photography and design how did you transition into creating these kinds of works?

I think in my work, everything is connected. Photography, animation, analogue, digital, design, music. What I do now came from all those backgrounds.

Are you working on any projects at the moment? What can we look forward to seeing from you in the future?

Yes, I am working on several projects. But shhhhh. I can’t talk about them yet.