“Our music celebrates the coefficient of randomness that is unleashed by uniting multiple minds.”

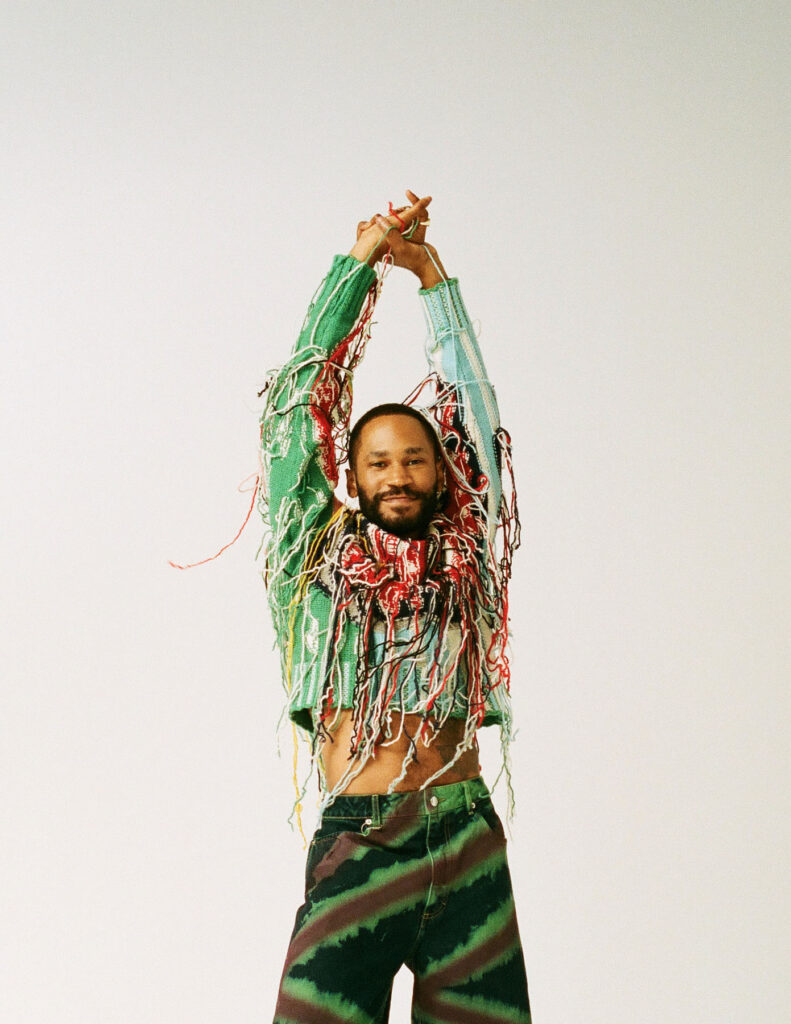

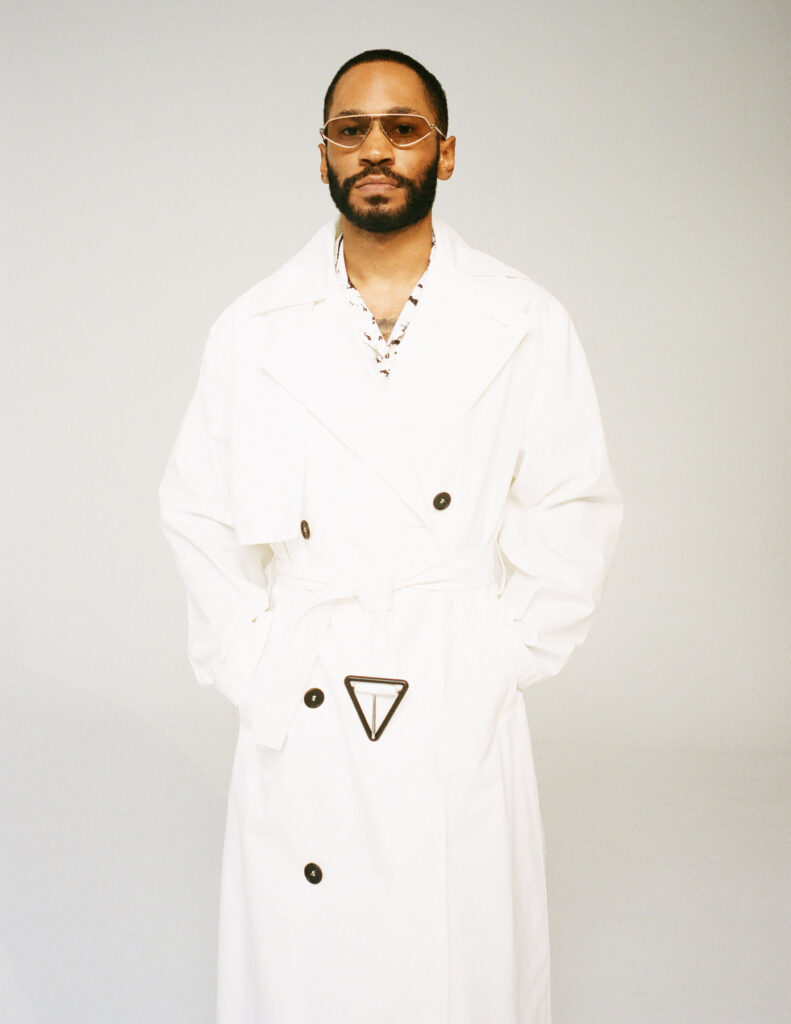

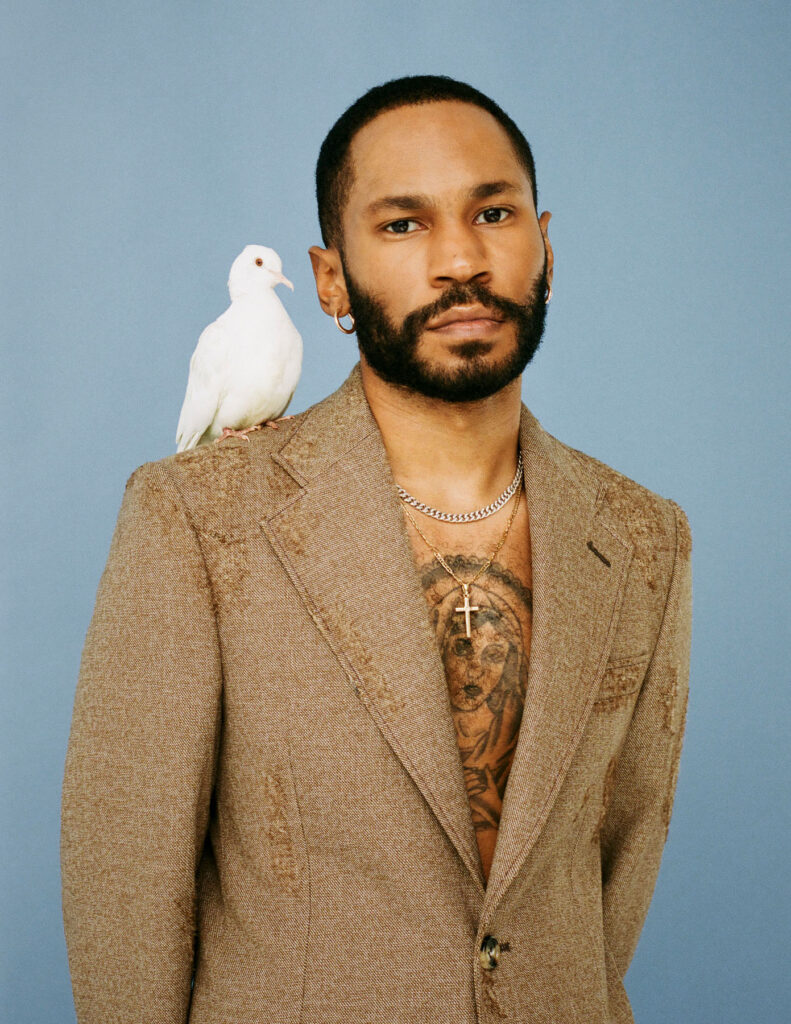

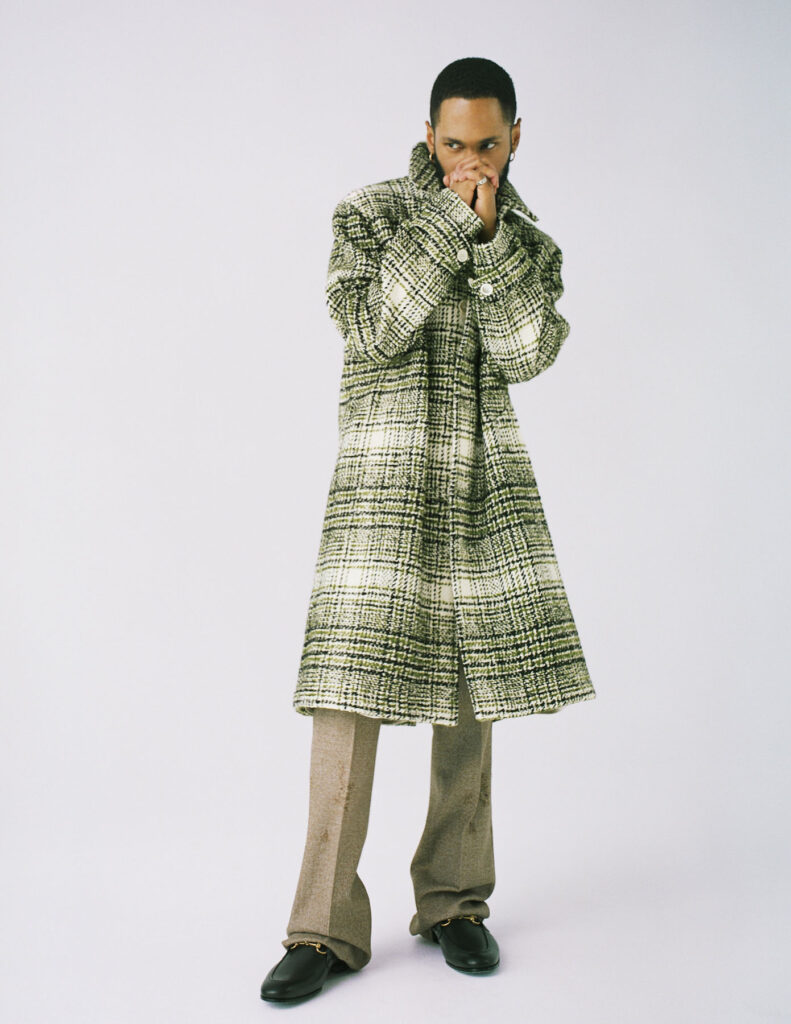

72 Hour Post Fight is an experimental project between two Milan-based producers and musicians. The group, whose debut eponymous album was released in 2019, exhibits a range of expertise and sounds; there’s guitarist Carlo Luciano Porrini (aka Fight Pausa) who was previously part of the emo band, LEUTE; Luca Bolognesi (aka producer, Palazzi D’Oriente); saxophonist Adalberto Valsecchi and drummer, Andrea Dissimile, who was also a part of LEUTE. It’s safe to say, then, that 72 Hour Post Fight have a pretty solid grasp of the music scene they’ve since (re)entered as a quartet. Their debut album introduced the music scape that has come to define their approach (an approach best described as just seeing where things end up going – as the band explain to NR below). Pairing ambience with moments that err towards the disconcerting, it’s an ode to the diverse background each band member brings – and their desire to see what they can create out of that. More than that though, their sound communicates the wide-ranging music each member grew up listening to – for example, friends since school, Carlo and Luca dreamed of forming a punk rock band – but be under no illusion that 72 Hour Post Fight are following in the footsteps of any one band or genre. The band released a remix version of the album also in 2019, which is a beautifully layered reinterpretation of what 72 Hour Post Fight first debuted. Their 2020 EP, NOT / UNGLUED, meanwhile, listens like a slick, tightened-up follow up to 72-HOUR POST FIGHT – a testament to the band’s hunch that working together might pay off. Now, they’re gearing up for the release of their latest single at the end of March. Made of Clay takes a slightly different direction to the album and EP, but it remains characteristic of their output so far. It’s a slow burner, with separate elements coming into focus over the course three minutes – 72 Hour Post Fight seem in no rush to hastily reach a crescendo, and their music is all the better for it.

NR: There’s a lot of diverse sounds in your music, how do you coalesce elements of jazz, electronic, and so on?

72PHF: We actually don’t combine them at all! Our music certainly derives in large part from already existing music and genres, but every reference is purely coincidental and based on our musical backgrounds. On our first album the compositions were mostly based around sampling and saxophone, so this made our music easily comparable to jazz, hip hop and electronica. With this second [upcoming] album, the backbone of the songs is songwriting, and none of us are really purely jazz or hip hop musicians so other inspirations shine through as well. This choice of redirecting our writing approach made us stray even further away from a canonical classification of genres.

“If we had to express it in a word, we play non-background music – and in this container there is potentially room for everyone.”

NR: What can you share about your single, Made of Clay?

72PHF: Made of Clay is a simple song. It’s very emotional and thrusting, and it has a certain decisiveness about it that we fell in love with. It started from a guitar riff that sounds taken straight out of our childhood’s CDs, and ended up being something new. Adalberto wrote this beautiful saxophone melody that narrates throughout the song, and Andrea came up with a simple and effective drum pattern for the last section while recording that really brought the song together (we actually had to cut our applause and cheering at the end of the take!) It’s not always this easy, but this time it was.

NR: Going back to the different elements in your music as well as references to indie and rock in Made of Clay. What do you think of categorising your music within a genre? Is that important, or not?

72PHF: The categorisation of our music is an external, ex-post fact that happens when we look at our music finished, with fresh eyes. We feel that trying to classify a song while it’s still being worked on could trap us in an uncomfortable comfort-zone, where we kind of know ahead of time the logical next steps to take to make it work.

“We are overthinkers by nature, so we tend to manufacture this randomness and chaos to give us the freedom to experiment and let our influences unravel, creating what we need to communicate, instead of what we should. Made of Clay was born exactly out of this need.”

NR: Besides 72 Hour Post Fight, you’ve all been part of other projects or played different kinds of music. How do you collaborate together as a band?

72PHF: Coming from different backgrounds is a precious part of our creative journey. We all have different tastes in music, and it often happens to drive back home after rehearsals listening to some new music we recommended to each other. This is stimulating both our friendships and our creativity. Indeed, the writing of our last album has been a back and forth of ideas, constantly sending audio files and feedbacks, always trying to keep the desire to surprise each other.

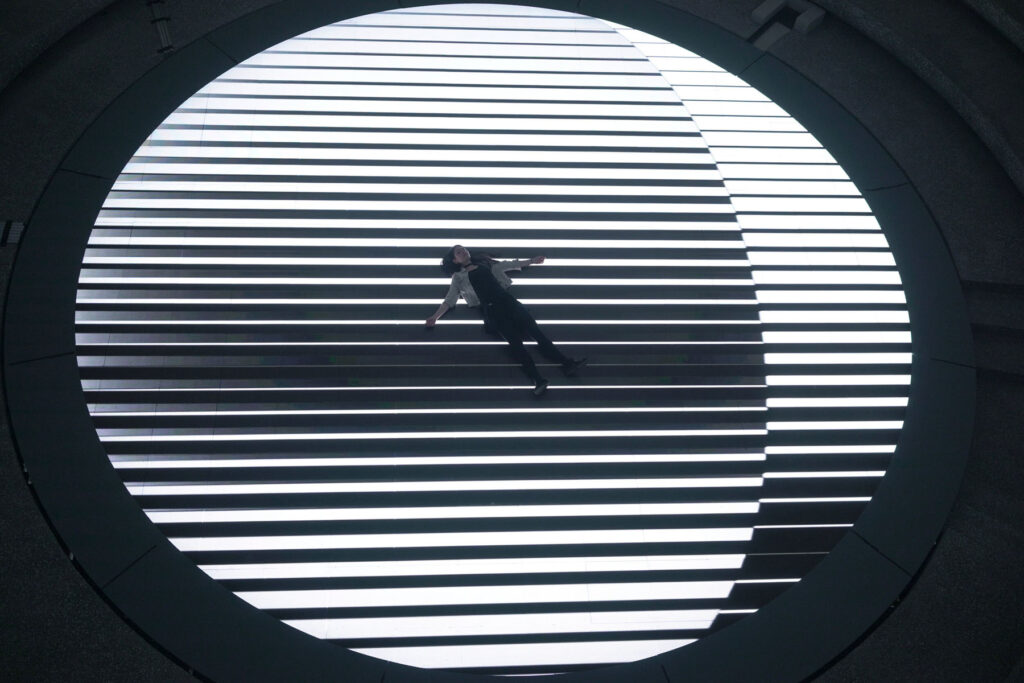

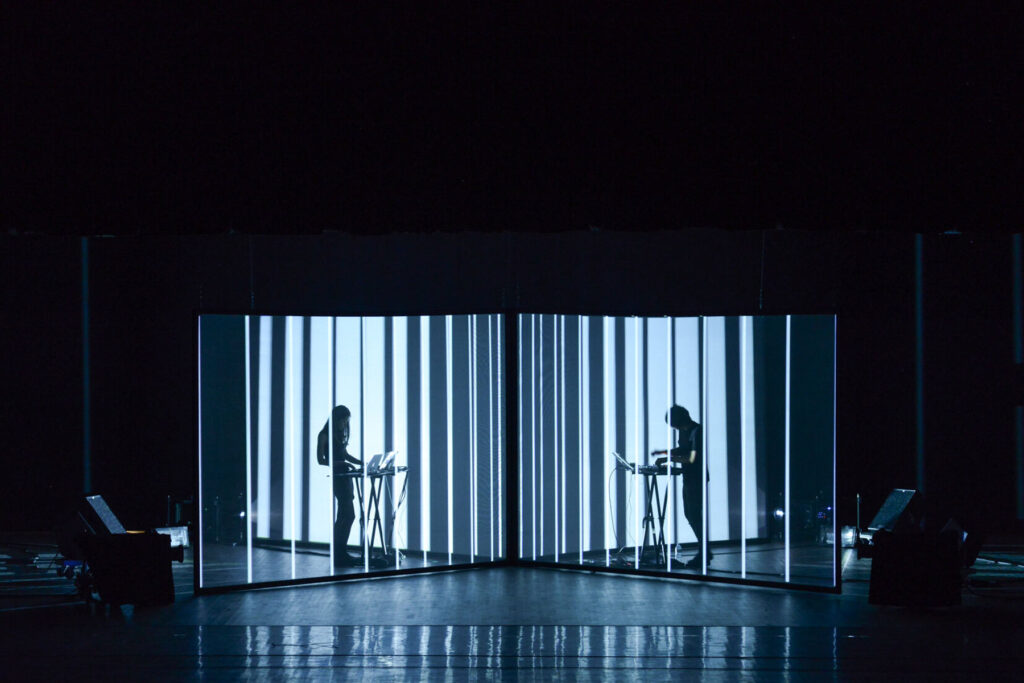

NR: What does a 72 Hour Post Fight live show look like? (Or sound like!)

72PHF: Our shows are very energetic and improvisational. We have a lot of fun, but we also have to constantly be on the same page. Instruments take over. The songs we play are alive creatures that always change on stage, based on our feelings that night and our synergy. The show is very physical in that sense, we try to create an organic and lively experience alongside the audience. If you want to get us, you have to come and see us!

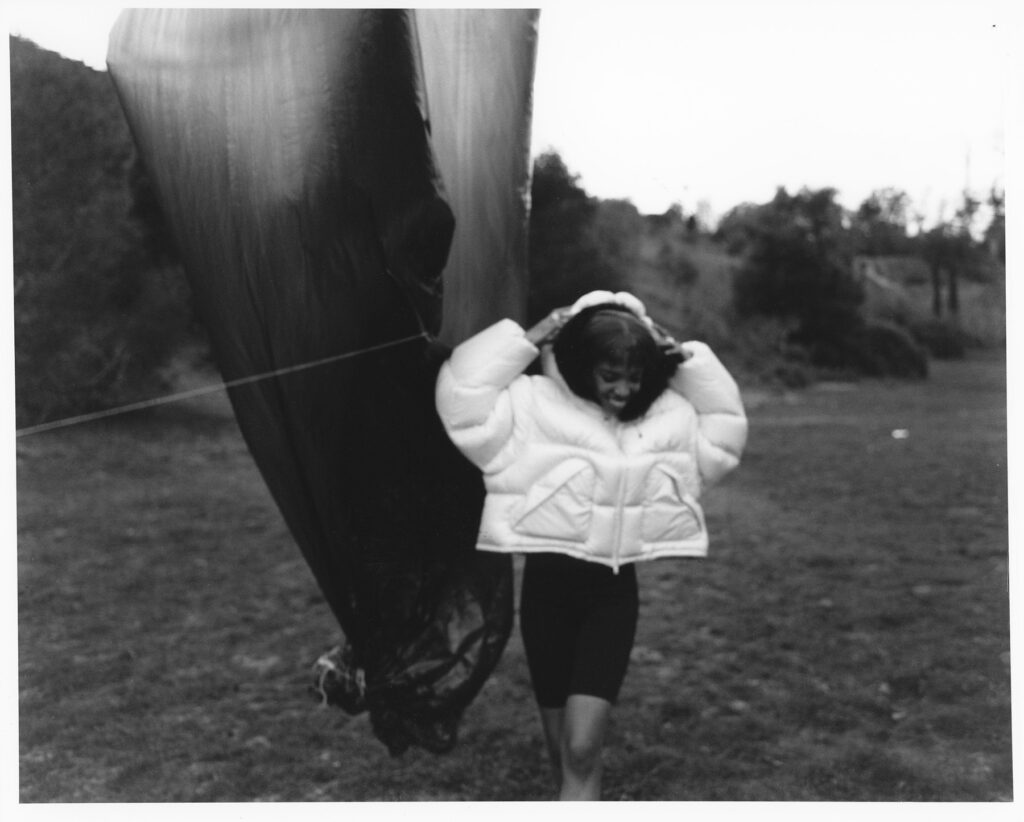

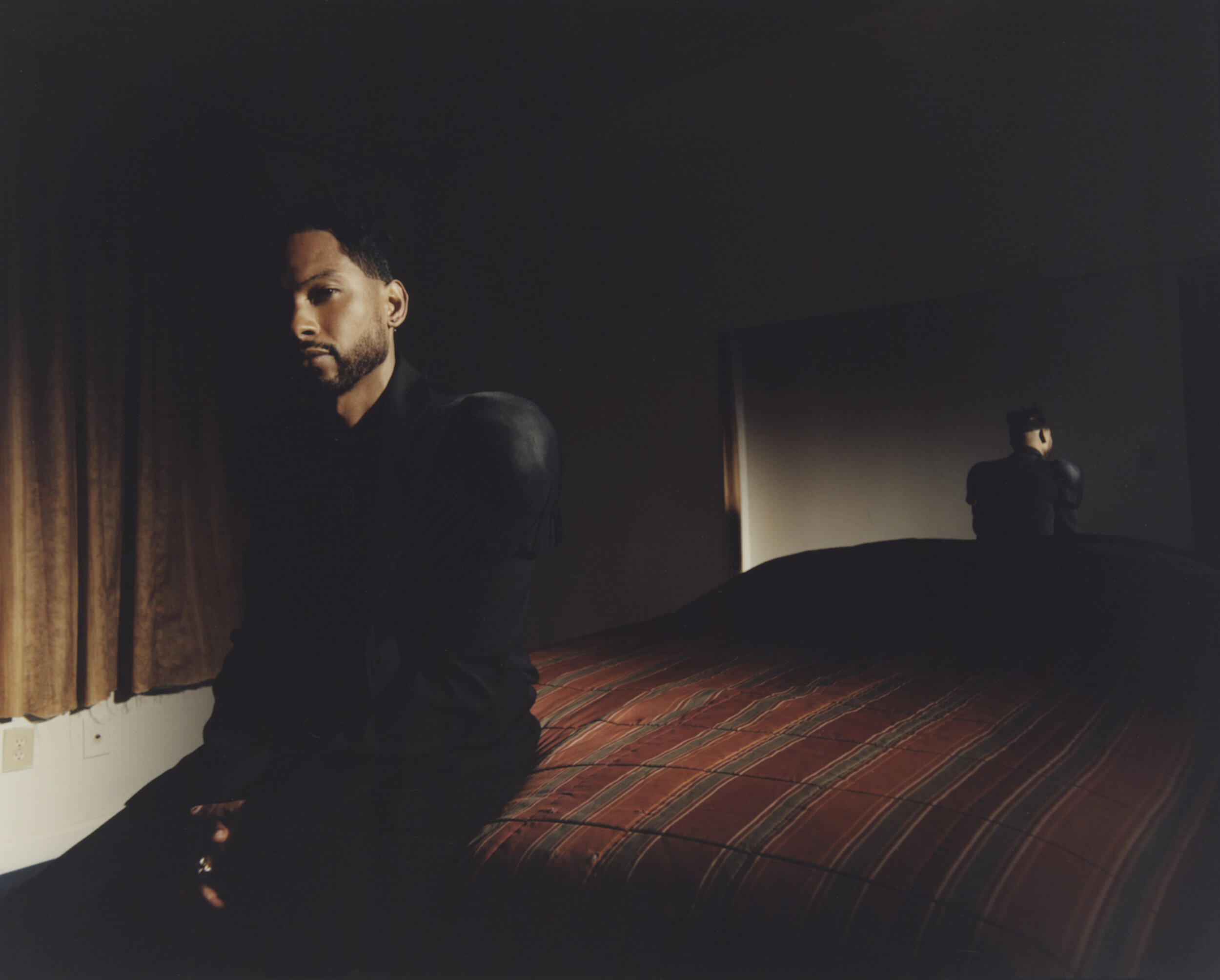

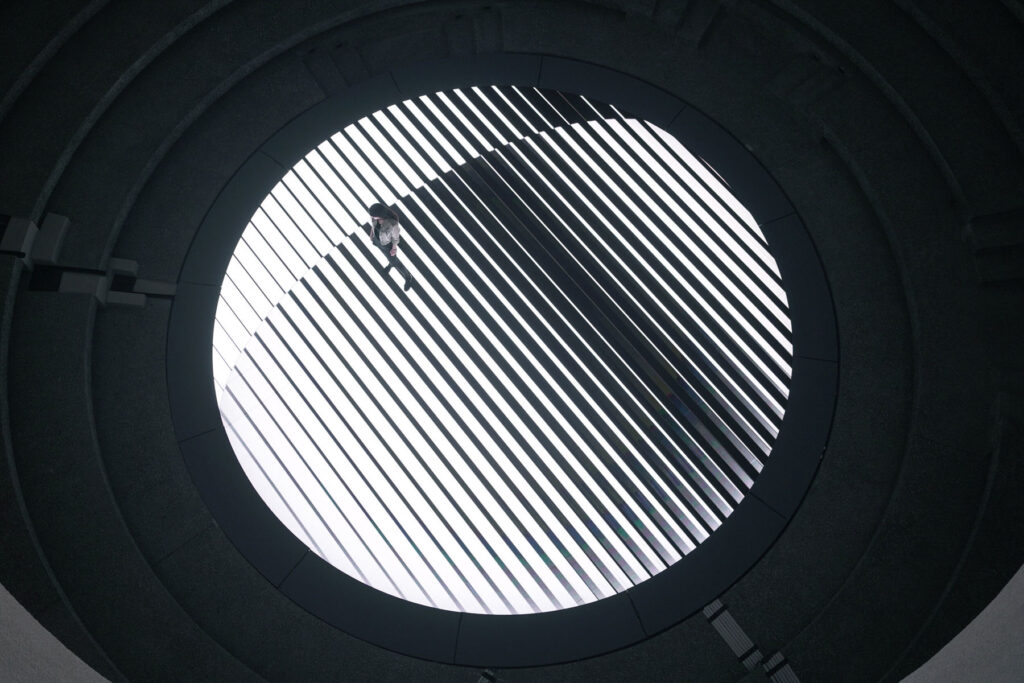

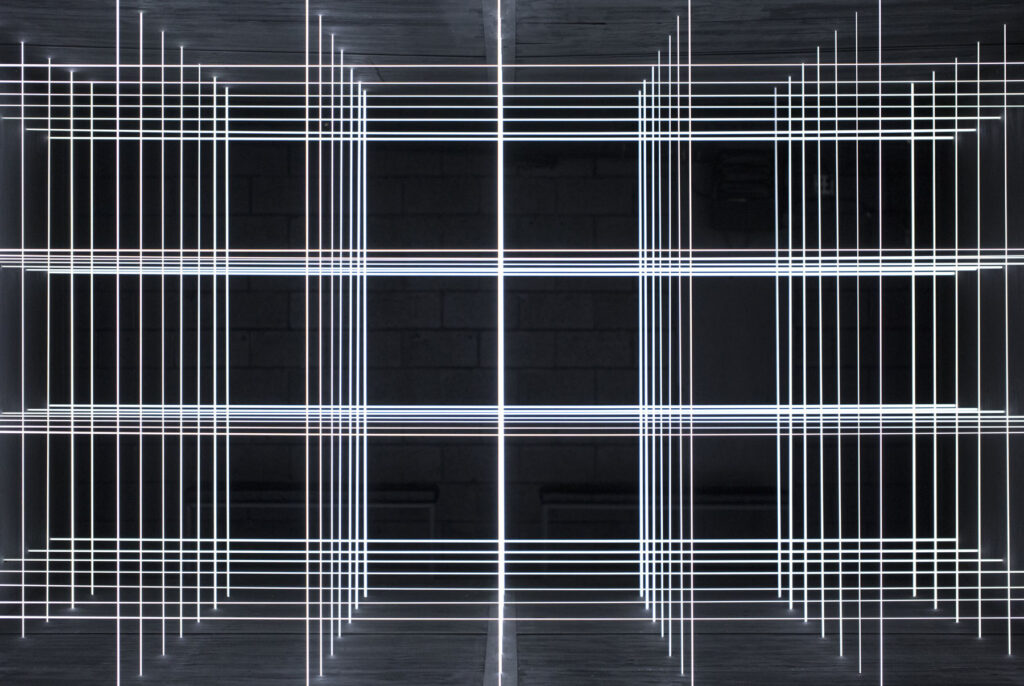

NR: Thinking about the album art for your music (especially the EP, NOT / UNGLUED), would you say that 72 Hour Post Fight has a certain aesthetic? If so, how would you define that?

72PHF: We care a lot about the aesthetic of the project. We are lucky enough to work with amazing people that help us get our ideas from a crazy, abstract input to the real thing. During the NOT / UNGLUED EP release we started working with Giorgio Cassano and Nic Paranoia for the art direction of the project. They are young and talented creative minds, and they really helped us take the project to the next stages. We had this idea of a clear flexi-disc as a cover, and we wanted to incorporate our long-time friend Francesco Mastropietro’s drawing on it, and this slowly kickstarted the idea behind the whole album art. We even managed to turn the render into the real thing! For this new round of artworks, we decided to include in the project an incredible Portuguese-American visual artist, Bráulio Amado. This is the first time we worked with someone completely outside of our team, and we’re thrilled to experience the vision of another artist who doesn’t know us personally, but only through our music.

NR: As a final question, what would you say that your music, or your work together as a band, celebrates (the theme of the magazine)?

72PHF: Our music celebrates the coefficient of randomness that is unleashed by uniting multiple minds. We feel like this is the best way we found to let our music manifest. As authors and producers, we are always very strict about our solo works, but whenever we throw an idea at the band the result it comes back with is highly unpredictable. Even if we find ourselves far from where we thought we were going to end up compositionally, the song assumes its own independence and dignity that makes it perfect. Even now, listening back to our own discography, we wouldn’t change a thing, which is really shocking for control freaks like us.

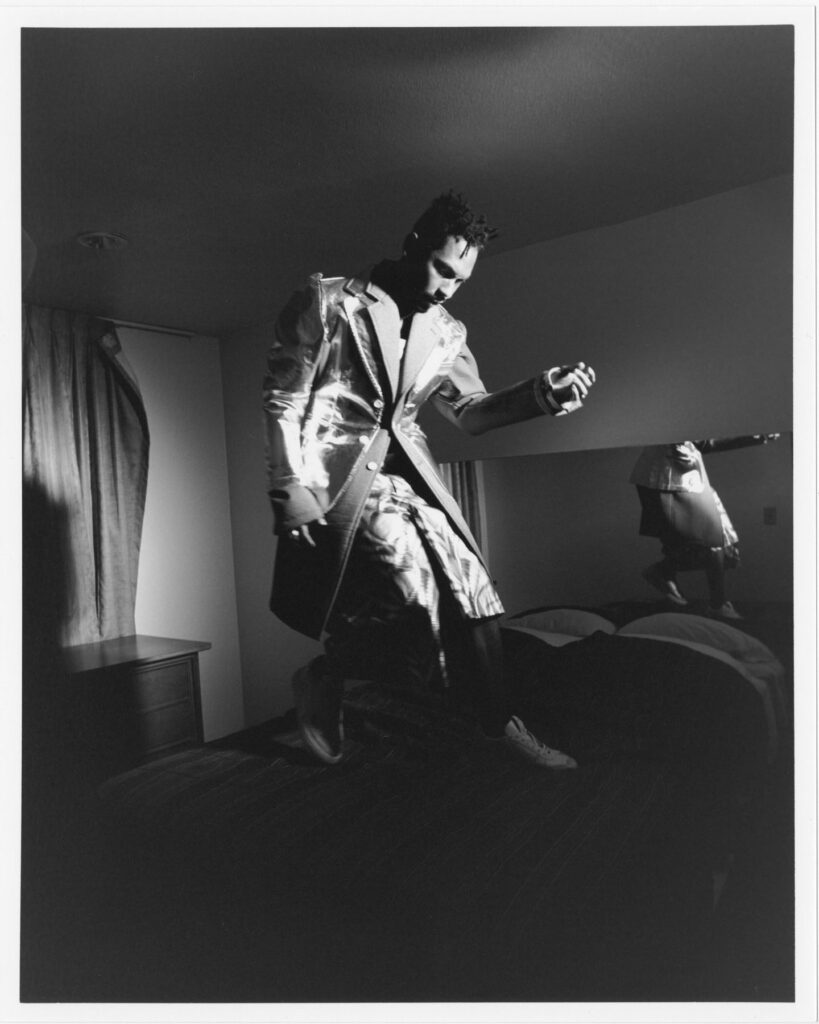

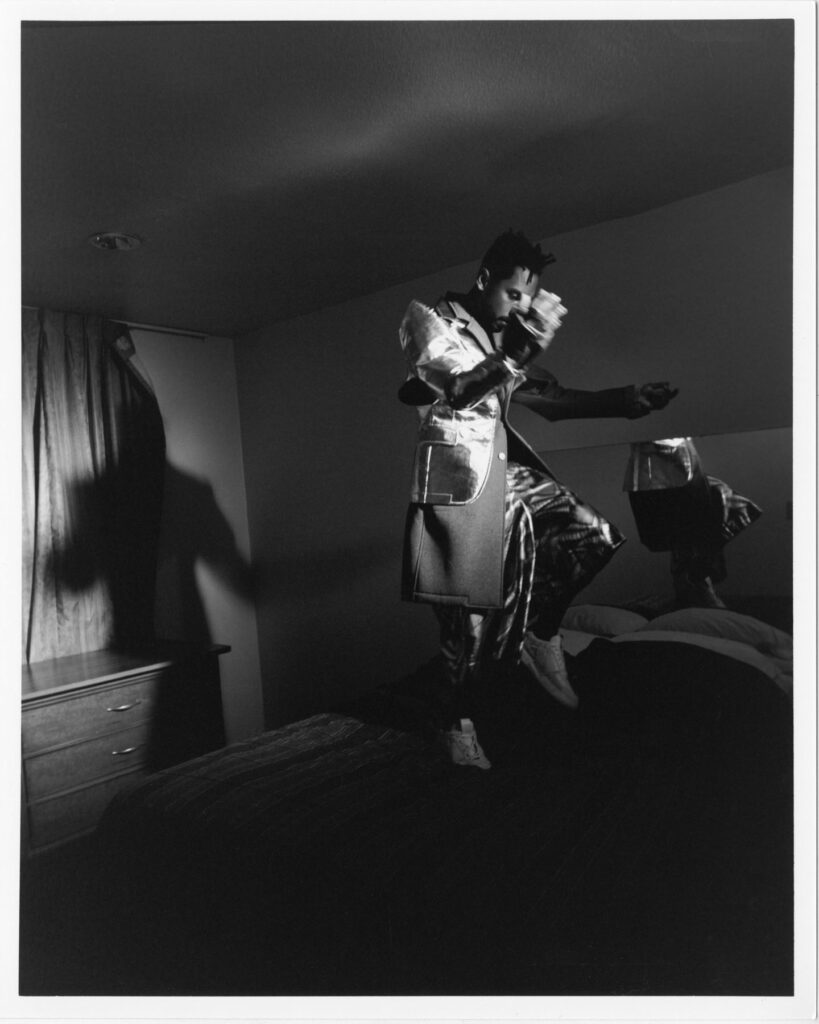

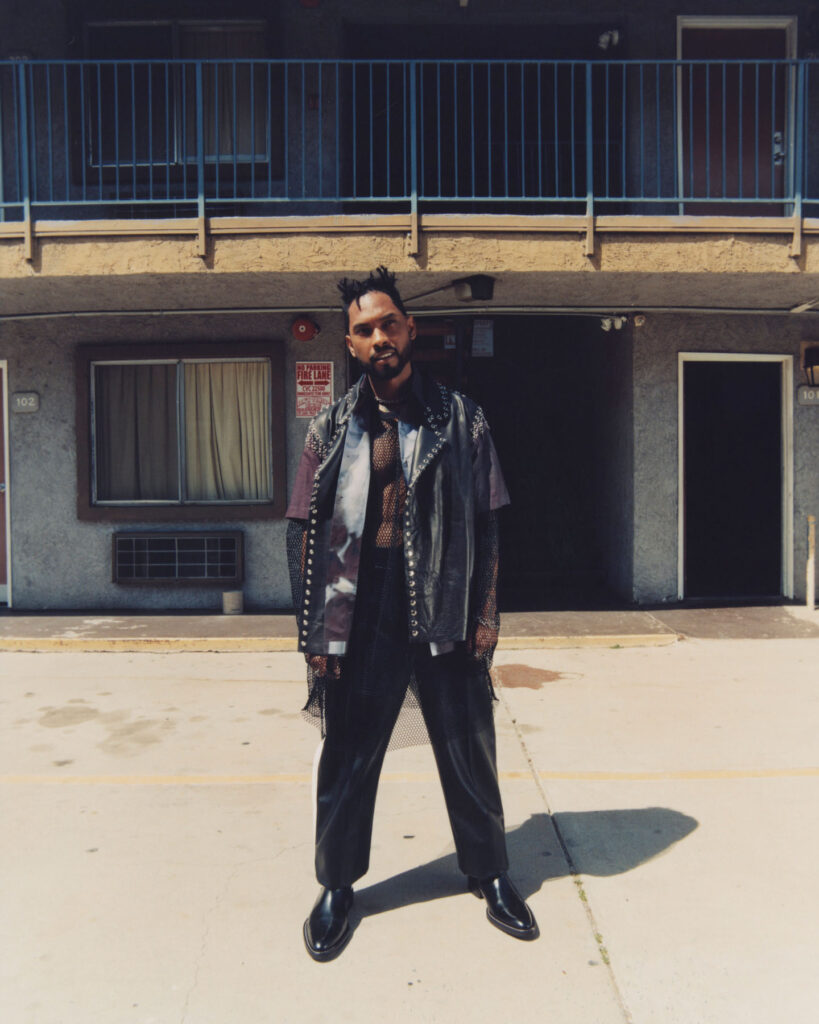

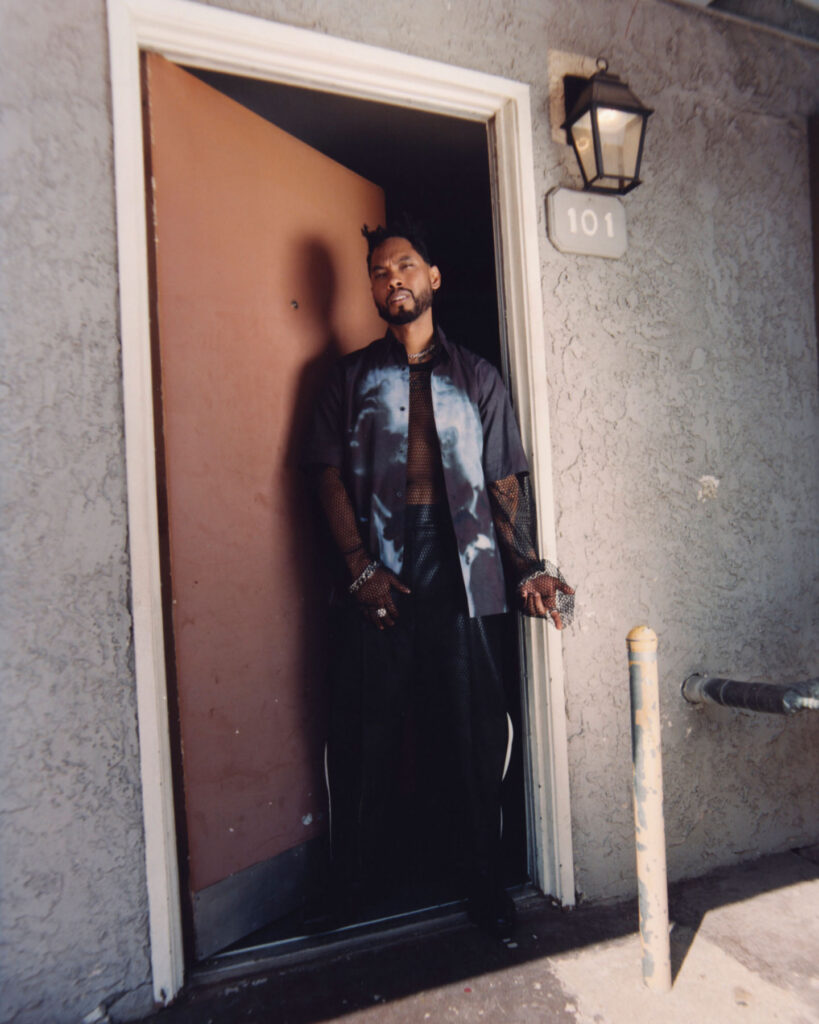

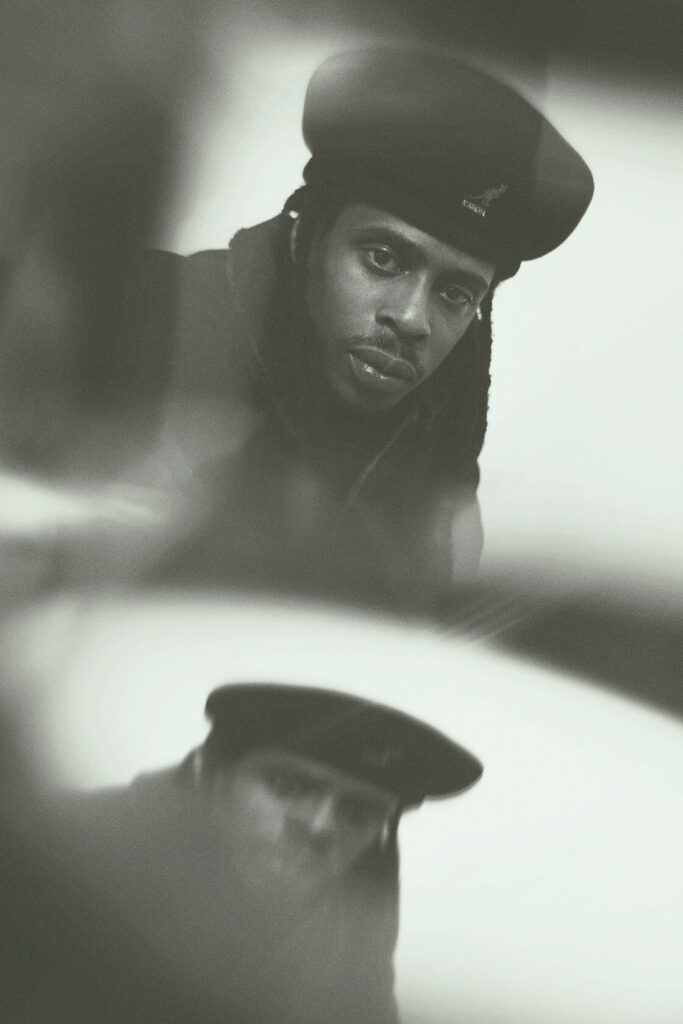

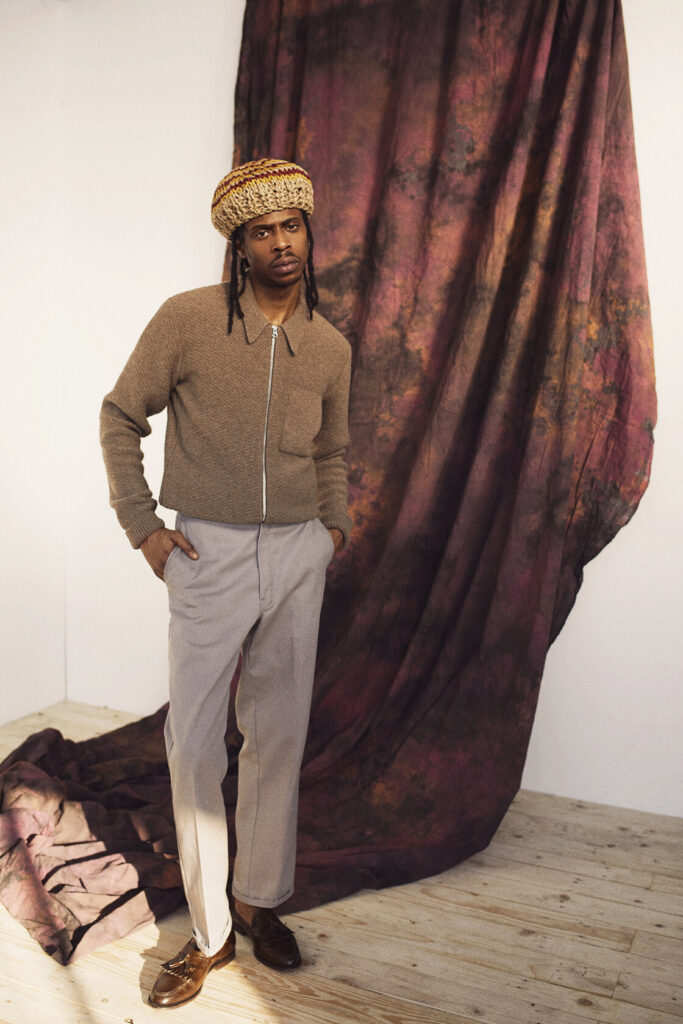

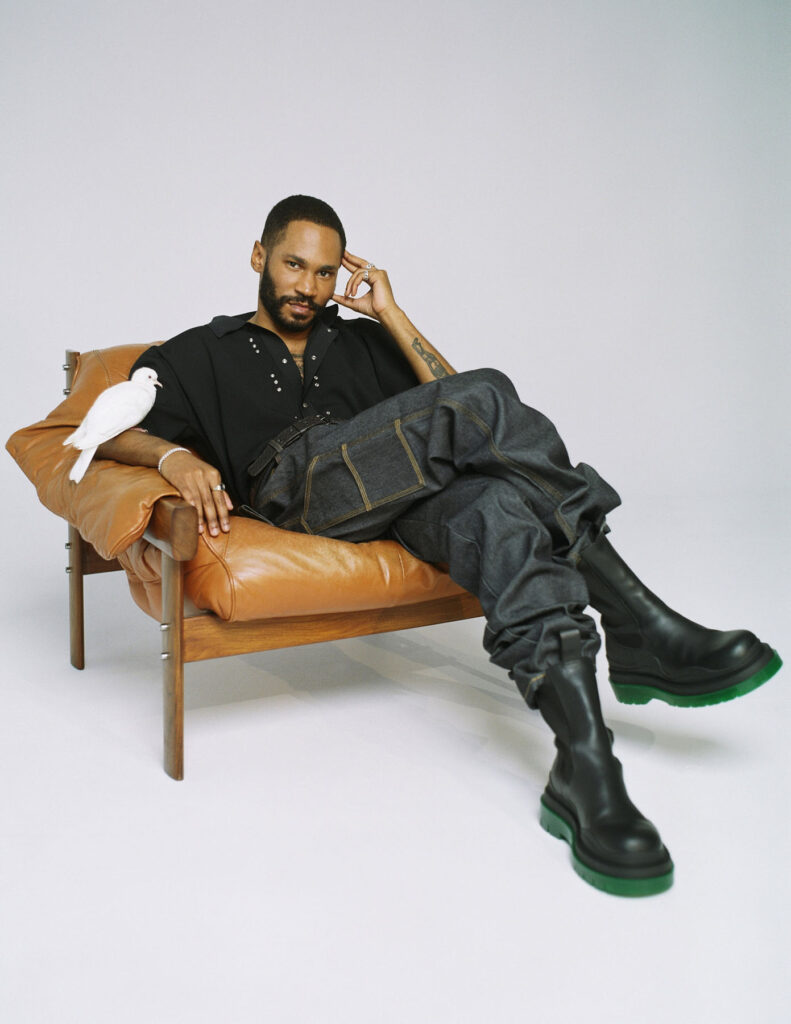

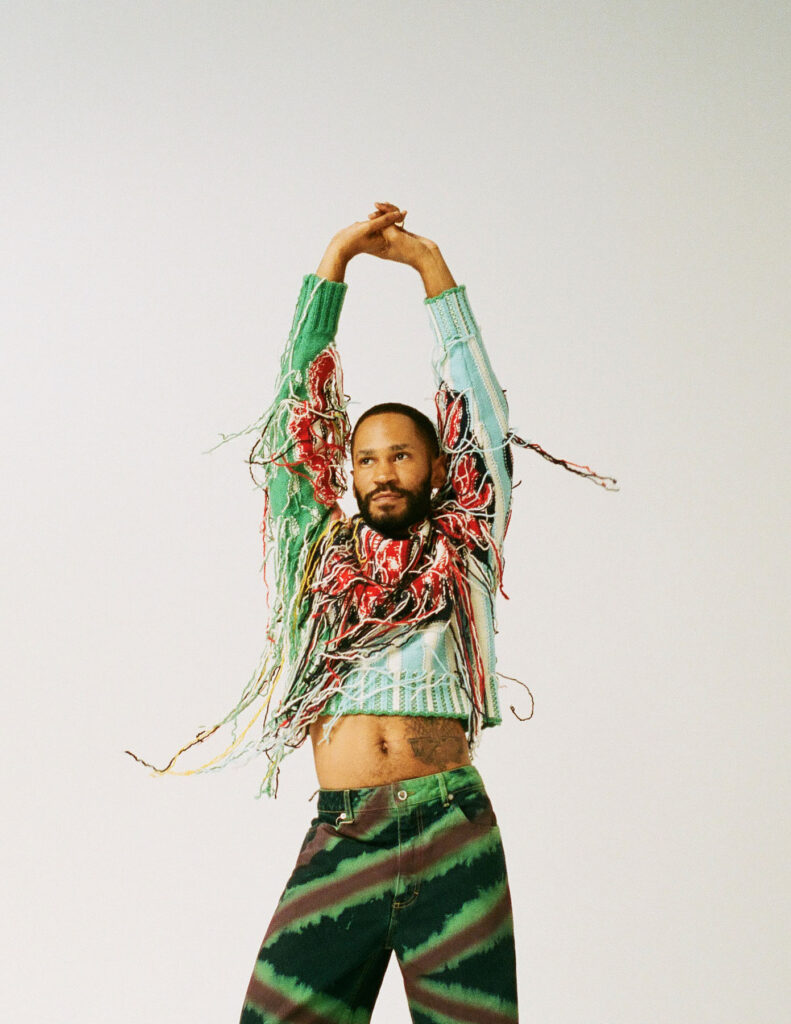

Credits

Images · 72 Hour Post Fight

https://www.instagram.com/72hourpostfight/