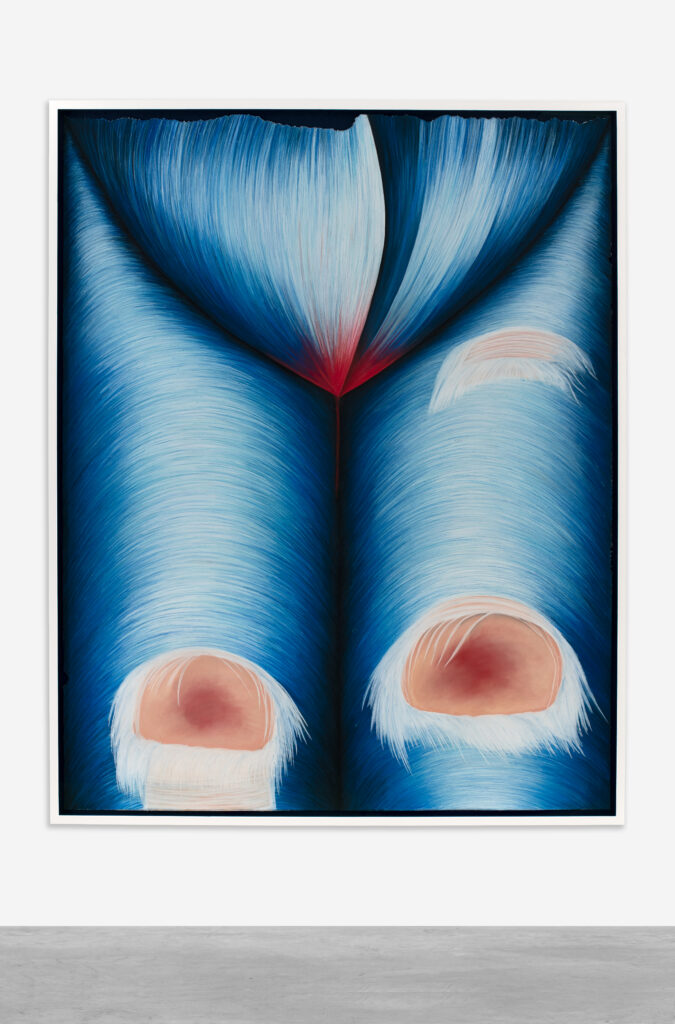

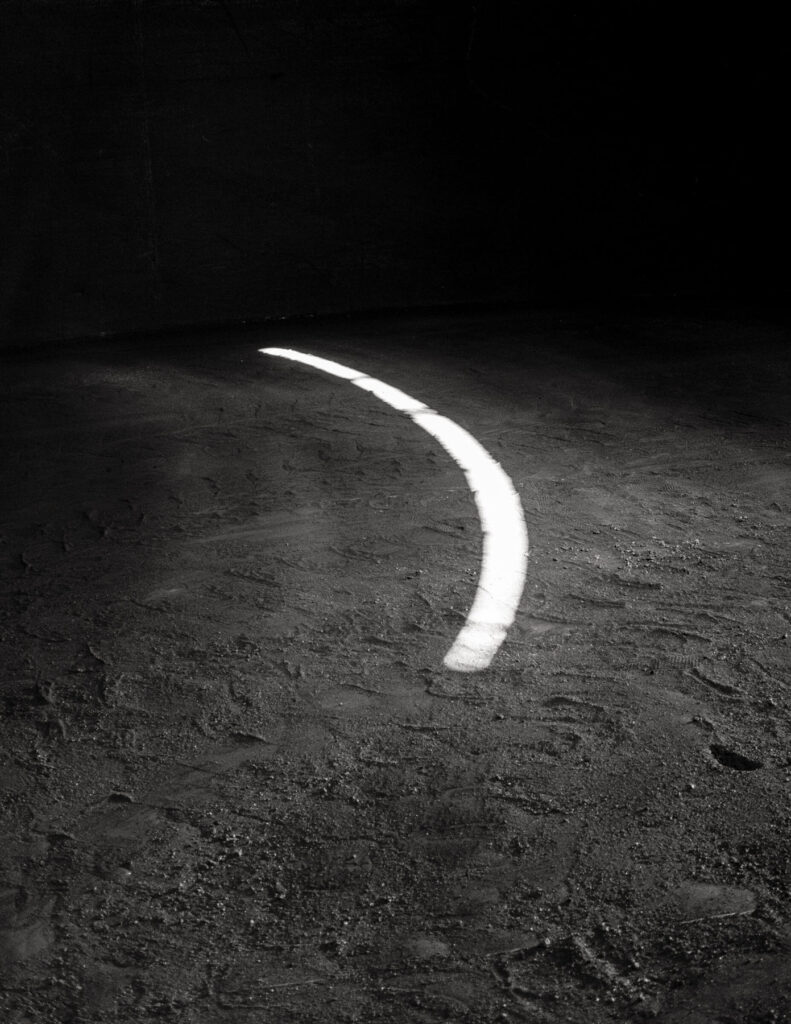

Ayse Erkmen, Luminous, 1993-2015

Installation view, SMAK, Ghent, 2015 Photography by Dirk Pauwele

Unhooked meanings transcending the worlds of architecture and spatial design

Ayşe Erkmen (born 1949, Istanbul, Turkey) is one of Turkey’s most important visual artists. Her practice has long examined the social and political implications of physical space including infrastructure, urban planning and architecture. Currently based between Istanbul and Berlin, Erkmen transcends the world of architecture and spatial design and pushes the boundaries when it comes to the transformation of both indoor and outdoor sites. On Water, 2017, a beautiful installation that debuted at the international open-air exhibition, Sculpture Projects, in Münster, Germany, is one example of Erkmen’s visually striking site-specific installations and demonstrates the importance of the audience in the completion of some of her artworks.

NR joins the sculptor and artist in conversation to discuss the influences that have informed her practice, how her work pertains both in Istanbul and Berlin and how it engages with specific histories and culture. Erkmen delves into the nature of a certain leitmotiv present in some of her work and the concepts behind Plan B, 2011, Pond to Pool to Pond, 2016 and On Water, 2017.

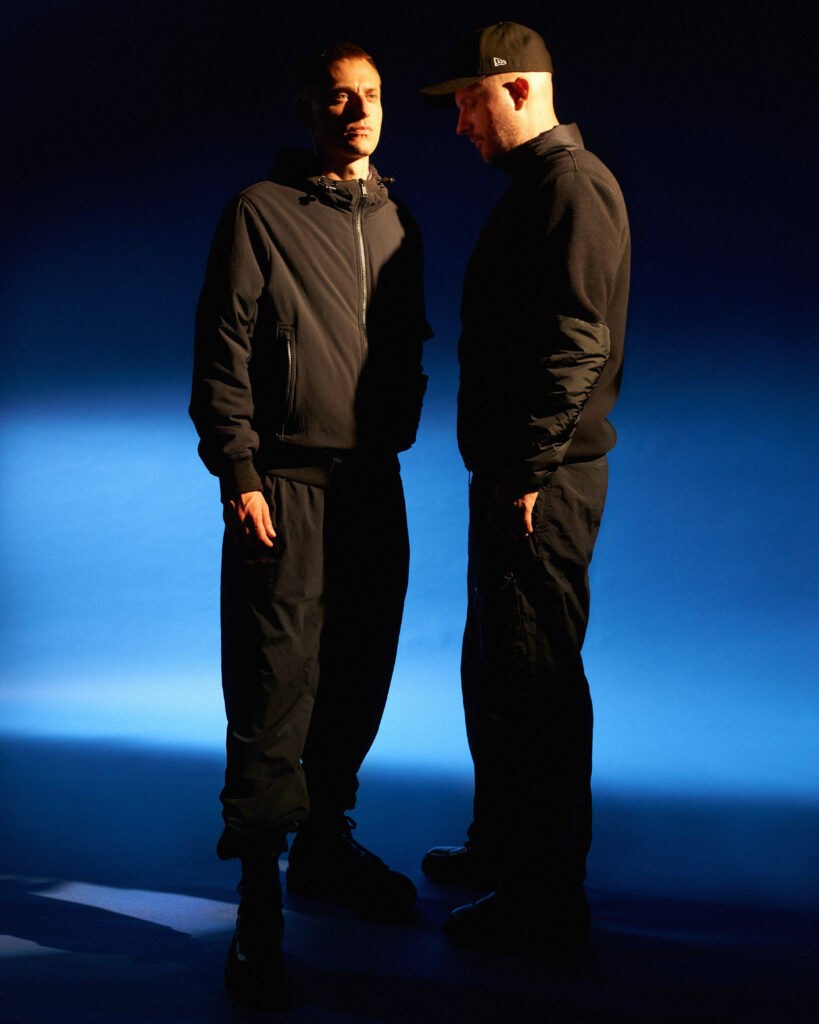

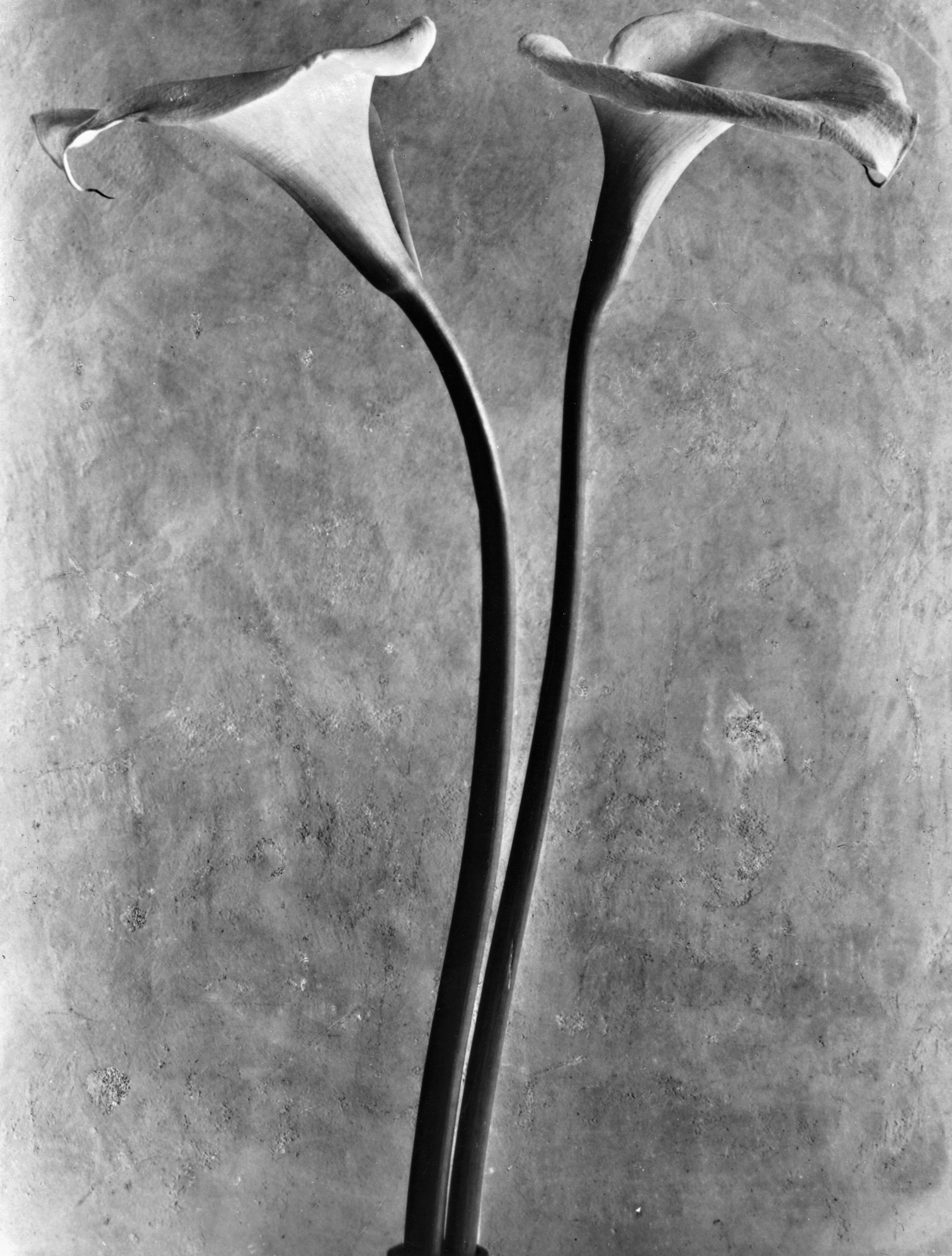

Ayşe Erkmen. Photo Credit: Serdar Tanyeli

Ayşe is a beautiful name. I have read that it means happily-living one. Would you say you are?

I think so too, Ayse is a beautiful name and I am grateful to my parents for giving it to me. It not only means happy but also moonshine and life, a very popular name, short and modest, shared by all generations and all social groups. Yes I am a happy person in general with lots of anxieties which strangely do not prevent me from being happy. Actually I believe that anxieties are one important ingredient of happiness. Happiness without worries would be a kitschy one.

You are recognised as one of the foremost Turkish artists. What does this mean to you?

I don’t think I understand myself as one of the foremost Turkish artists. Actually I would not like to be known as a Turkish artist but I guess one cannot escape its origin. I like the fact that I am from Istanbul though, for having had the chance to being very familiar with this amazing, vicious city, an opportunity like my name, something that happened to me. My fame is kind of strange. Young artists know me very well and they appreciate me as I also appreciate very much this fact of being popular among young generations. I had been teaching in Germany for quite some time and I am hoping that I have had some influence on this. As to the fact of being collected, earning money, being the muse of art fairs, etc.. this is not me. I guess, I have a special place in todays art context: people seem to like my work but they don’t know how to place it in their lives. I am hoping that the reason is that I am giving them something new that they have not yet known, they haven’t seen or did not think about before, therefore not confirmed yet!

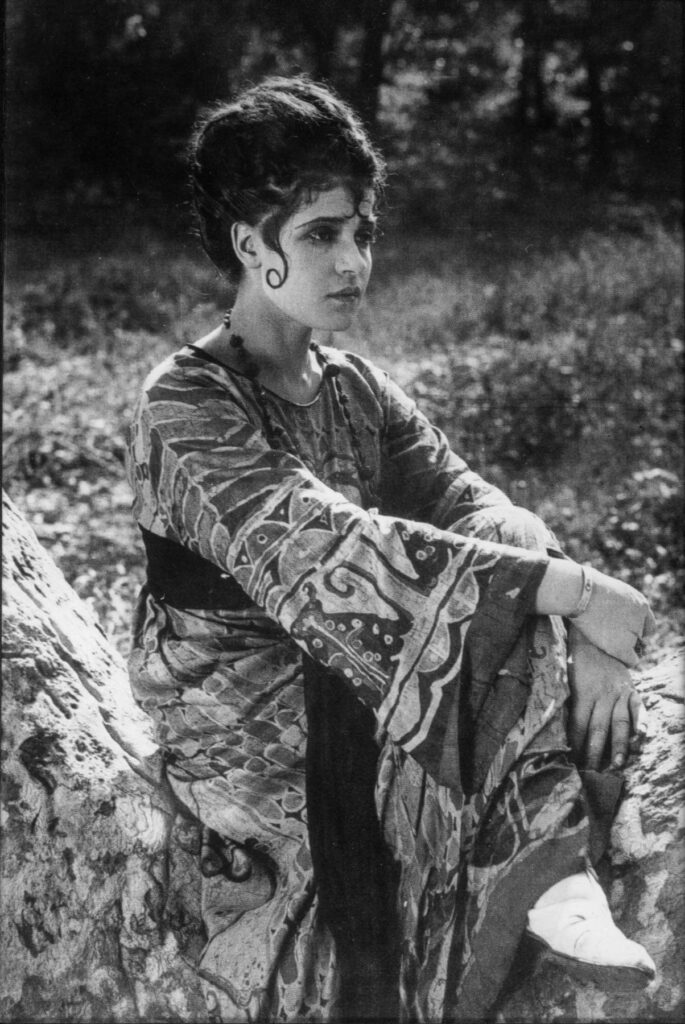

Let us Cultivate our Garden (Group) (curated by Fulya Erdemci and Kevser Güler). Cappadox Festival II, Cappadocia (Turkey), 19.05. – 12.06.2016. Exhibited work: Ödül / Prize, 2016. 142 Site-specific installation Photo Credit: Murat Germen

You are currently based between Istanbul where you were born and Berlin. How do these two cities inform your practice? Do you see any correlation between the two?

I have to quote musician/artist Ahnoni here who once said: “I want to go but I don’t want to leave” on a similar situation of living in multiple places. I feel exactly like that, always looking forward to the other place but sad to leave the place I am in. Istanbul being a difficult city as it is, makes me happy by just being there, the shout of its seagulls, the smell of the seawater, the honks of the boats, even the most serious conversations ending with chit-chats, its noble stray animals and endless variations of life style.

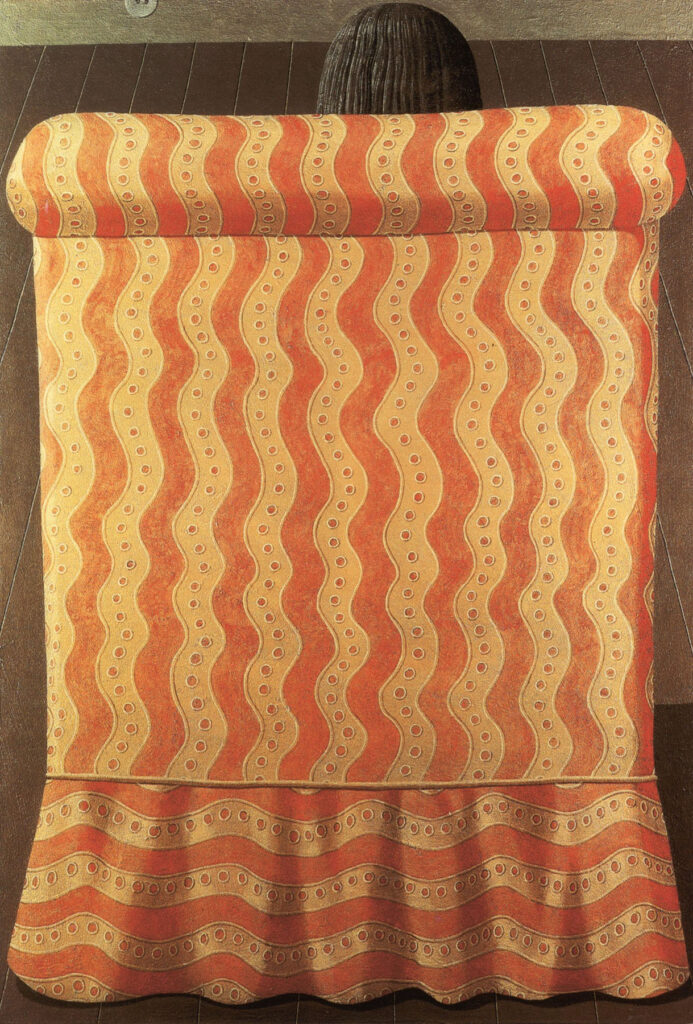

Ayşe Erkmen – Half of (Solo). Galerie Deux, Tokyo (Japan), 14.09. – 22.12.1999. Exhibited work: Half of, 1999; Photo Credit: Artist archive

Berlin a contrast but a good companion to this city; being so peaceful, easy and quiet if it were not for the official gray recycled envelopes of bureaucracy which one receives frequently. There, the small talks do not continue long and conversations turn into culture and art which is wonderful. Berlin is a city with so many venues of art, music, theatre, etc that knowing that they are always there one neglects them and gives too much a rain check. Berlin is a city that supplies too and pampers its citizens whereas Istanbul does this only by being there in that location that every time it angers or disappoints the blue sky and the seagulls appear out of nowhere.

Water appears as a recurring element in your work. Why this leitmotiv and what is your relationship to it?

“Water is something I can’t escape as an art location whether it is given to me or chosen by me, be it a river, the sea, a canal or a small pond. I always have the strong feeling that I should not lose this chance of being on water or using water as material whenever I can catch the opportunity.”

Skulpture Projekte Münster, 2017 (Group) (Catalogue) (curated by Kasper König, Britta Peters, Marianne Wagner). Stadthafen 1, North side: Hafenweg 24, South side: Am Mittelhafen 20, Münster (Germany), 10.06. – 01.10.2017

Exhibited work: On Water, 2017

Site specific installation: ocean cargo containers, steel beams, steel grates, 6400 x 640 cm walkway

Photo Credit: Roman Mensing

These fortunate offers make the recurrence in my work, unlike other repeating elements like animals, like stones and rocks, archival images, etc that are much more of a choice of mine. Water is not stabile, it moves and makes things move, It has power to create unexpected occasions and coincidences. I am looking for these instances that surprise me as moments that I do not have much control over. In some works I made buoys in water move balls on land which directly relates to the unpredictable movements of water’s effect on land. This makes continuously changing sculptural moments. In my work this is in general what I am looking for. Things that happen without the artist’s intention, water is chance.

“Besides there is the beauty of water that one cannot ignore although I would not want to be in a position of getting advantage from such a glorious appearance. I try to be as neutral as possible mixing it with contrasting technical vehicles that are invisible, unwatched companions of water.”

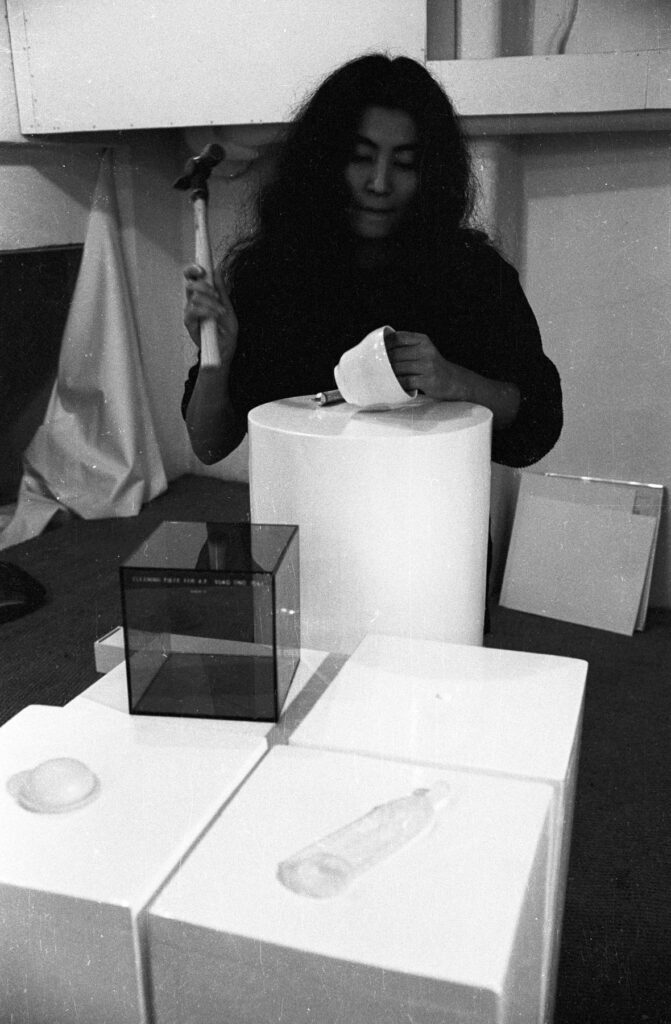

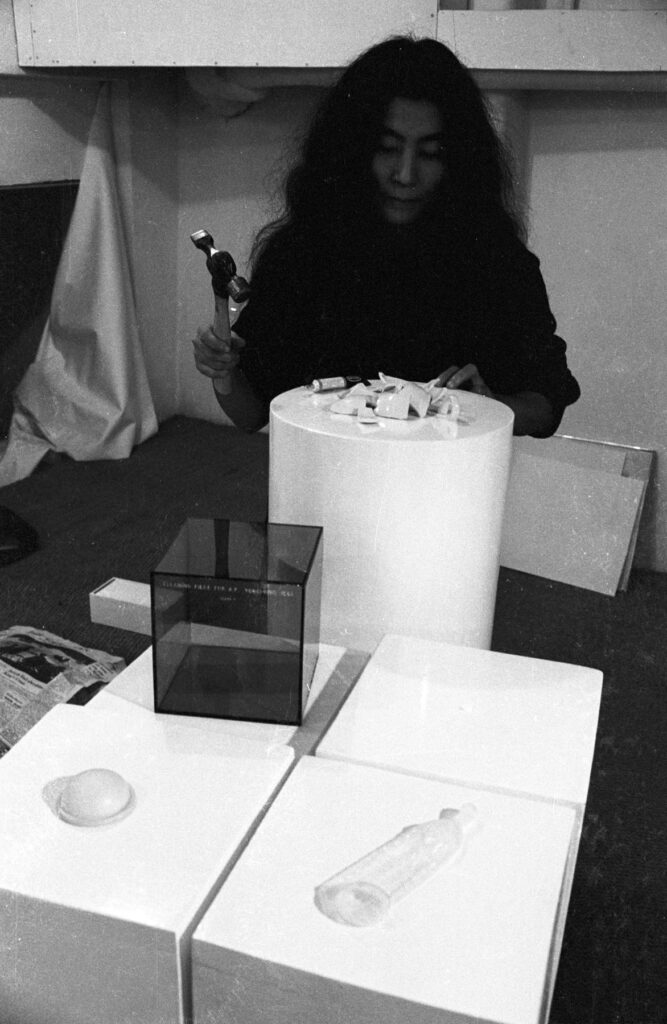

Could you delve into the concept for Plan B, the installation at the 2011 Venice Biennale, that transformed the Arsenale exhibition venue into a room for purification?

Plan B was prepared in a very short time, I still cannot imagine how we could achieve that project in four months only. Fulya Erdemci; the curator was selected in December before. She had to think which artist to choose for about two months. After being appointed by her I had to think what to do for a while but it did not take long as at our first location trip I saw that the place given to us as pavillon location at that time had the only window that opened to the sea/canal unlike the other rooms in Arsenale. This window to water told me that I had to find a way to bring it into this room one way or other. The canals of Venice that surrounds the whole city gave me the form and informed me that the room should be like the city itself surrounded by water. On the other hand the water needed to have an aim to come into this space. The most common thought about water is to drink it. There came the final idea.

Plan B (Solo) (Catalogue) (curated by Fulya Erdemci). 54th Venice Biennale, The Pavilion of Turkey, Artigliere, Arsenale, Venice (Italy), 04.06. – 27.11.2011

Exhibited work: Plan B, 2011

Installation: water purification system, pipes, pumps, cleansing machines painted in specific colors according to their function

Photo Credit: Roman Mensing

Then we found a very sophisticated water distilling company in the middle of Germany. Fulya travelled from Amsterdam, me from Berlin, we visited the company and started working to make the plan B exhibition. In four months time realised the work, we made an extensive catalogue edited by Danae Mossman from New Zealand together with Fulya Erdemci and we also made a wonderful tote bag designed by Konstantin Grcic. Our idea was that if people would not want to make the effort to come to our space almost at the end of the Arsenale, would definitely come to get their beautiful Grcic bags! And it happened! We met in London at Danae Mossman’s flat to make the interview for the book. Danae was living in London at the time, Konstantin from Frankfurt, me and Fulya from Istanbul but were in Berlin and Amsterdam at that moment. We met many times, travelled to Venice and to other cities, had lots of fun, all of us from different parts of the world.

Plan B was created from one unit of a mobile water purifying machine rented for the duration of the biennial. This device was dismantled, its pipes between units prolonged according to the proportions of the given space, heightened to various levels depending on the advice of technicians and at the end of the installation, we even added minerals for the sea water to became tasty mineral water. The pipes came into the room from the canal and went back to the canal. My first idea to make the visitors drink the water was given up and the title therefore became Plan B. Fulya Erdemci and I had a last minute thought that making people drink water out of this work would be a too easy gesture and make the work too popular and take it out of its real content.

Your work as a sculptor and artist transcends the worlds of architecture and spatial design. Have you ever wanted to also become an architect?

I never thought of becoming an architect. Architecture and design always has purpose and function. I was and am still interested in purposelessness. I am always trying to achieve the most unhooked sense that aims to make the work be far from serving a reason or expectation.

U2 Alexanderplatz (Group) (Catalogue) (curated by “Arbeitsgruppe U2 Alexanderplatz”, Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst e.V. [NGBK]: Christoph Bannat, Uwe Jonas, Annette Maechtel, Tine Neumann, Barbara Rüth and Birgit

Anna Schumacher). Alexanderplatz, Berlin (Germany), 27.09. – 29.10.2006. Exhibited work: U8, 2006. Intervention: existing speaker, computer, sensor, two CDs (As each train pulled into the platform of line U8, dramatic-sounding music was played for the time it took the train to come to a stop. Two pieces were played, both in the fashion of trailer melodies used for television series.) Photo Credit: Artist archive

Each of your work engages with specific sites, histories, cultures and societies. How does your work respond to the situations you face?

A very good question and a very commonly asked one. Everyone asks me how my work responds to the site, its history, etc..The situations I face in a place is a very important part of this procedure. For example one of my most site specific work “Half of” for a gallery space of one room only (Galerie deux/Tokyo) was inspired simply by just the plan that was sent to me to introduce the gallery. Plan included the walls as well that when you folded the plan it became the maquette of the space. This was my simple inspiration for the work I made there which was consisting of five maquettes hanging from the ceiling, one by one becoming smaller, each one being half of the previous one . All was made effortlessly out of rice paper and wooden sticks by competent Japanese hand-workers.

Every work that engages with specific sites needs its own agenda which can be totally different each time and not necessarily with the expected inspiration. Sometimes it is history but a historical place can also get an artwork that has nothing to do with that because I also can have my kind of plans at the time which I want to realise urgently. Of course I feel the most successful when the work looks as if it had always been there or when I spend very little or no effort to make a work sparkle in the space or the best for me would be if I bring nothing to the space and only use the given elements of a space like my works with elevators for instance.

Pond to Pool to Pond, 2016, Japan and your most recent exhibition in Istanbul, I Insist, 2022 are other examples of your site-specific installations. How do you channel the premises of the spaces you use into your installation to reveal the space’s previously concealed features?

Pond to pool to pond in Nara, Japan is another version of a water cleansing work. In this exhibition each artist had been given a Temple in Nara to work with. My Saidai-ji Temple had a small pond which was dirty, almost like a swamp with lots of mosquitos. My aim was to clean this pond and to be able to do that, I installed a pool next to it. The shape of the pool was very much following the borders of nature placed in between trees and holy rocks. Between the pond and the pool, I installed the water cleaning and pumping system, much simpler than the Venice one because this time it just had to clean the pond. The pipes were installed to go inside the pool and the pond, the cleaning pumps were working continuously and carrying the dirty water back and front. In about a few hours both the pond and the pool were crystal clean and frogs started coming to the pond. The much needed balance of nature came back here and a bright blue colour of water with an unusual shape.

Art Projects at 8 Shrines and Temples – Travelling over 1300 Years of Time and Space (Group Exhibition) (Catalogue) (curated by Toshio Kondo, Art Front Gallery Tokyo). Culture City of East Asia 2016, Nara, Saidaiji Temple, Nara (Japan), 03.09. – 23.10.2016

Exhibited work: pond to pool to pond, 2016

Site-specific installation: already existing pond in site, connected to pool constructed out of wood, concrete, mortar, water and connecting pipes, cleansing and pumping machines

Photo Credit: Keizo Kioku

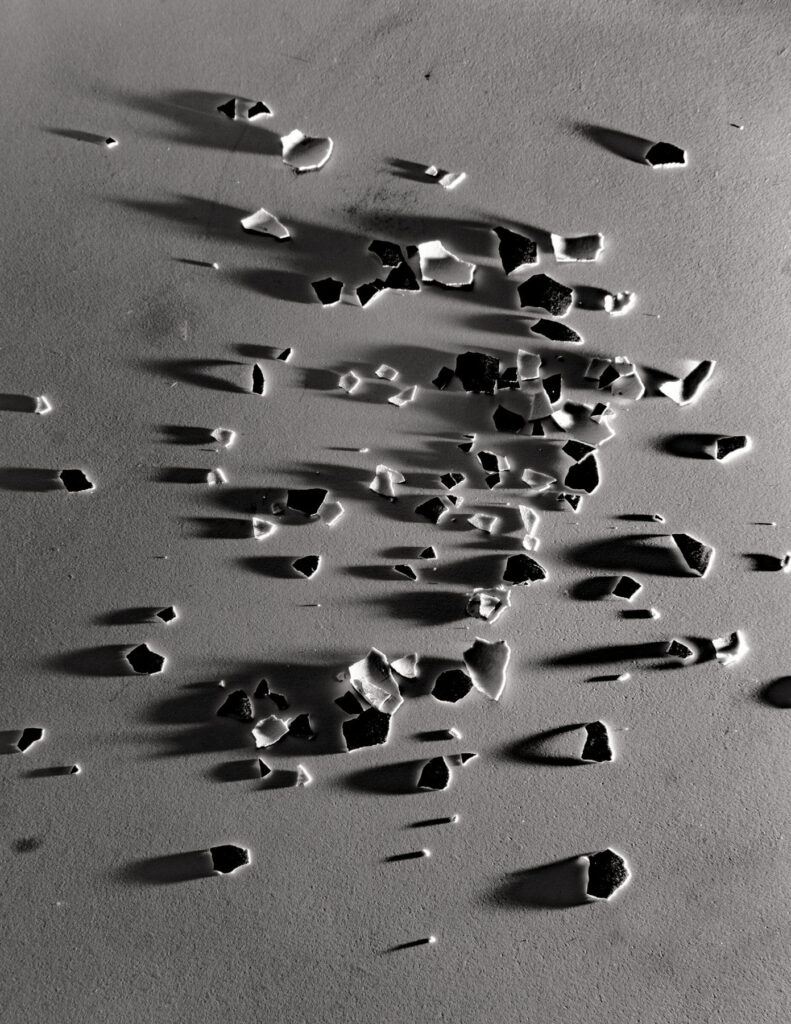

“I Insist” is an exhibition that follows another exhibition titled “Ripples” in the same gallery and uses the leftover material of the previous show. The previous show Ripples was about the unfair gentrification of an area in Istanbul and also about making a first show in a gallery that is part of this gentrification. I cut out rectangles off the new plaster walls of the clean, white cube like gallery space and hanged these wall pieces from the ceiling. The left over wooden panels on the walls at the back of these cut out plasters had white small circular traces created by chance. Aside from this I made a sound piece out of the reading of the names of all the shops and studios on the street leading to the gallery giving reference to the fact that these places will soon be the victims of this gentrification and will be gone in a short time. This was the sound of their archive, music of memories.

In the five years later exhibition “I insist”, I painted these leftover panels that had been hanging before; each one a different wall colour, each one a different size, handled with their cracks and breaks together and hanged them side by side on the walls of the gallery as if this is how they should behave, as paintings like what a gallery is for.

As can be seen in these three examples I have used the nature of one location/Saidai-ji Temple /Nara whereas I have used the politics of an area/ Dolapdere/Istanbul and in the third exhibition I have used politics of art /Gallery Space.

On Water, 2017, a beautiful installation that debuted at the international open-air exhibition, Sculpture Projects, in Münster, Germany took two years to be realised. People use it daily and the vision of passersby crossing the river whilst seemingly walking on water provides a beautifully striking scene. The public becomes an actor in this surreal scene. Could you talk more about the installation and its concept revolving around urban transportation and displacement?

The idea of the “on Water” installation came from the idea to be on Water. This was my second time of being invited to Sculpture Project Münster. My first contribution was moving sculptures on air by helicopter. The title of that work was “on Air” also giving reference to broadcasting. From being on air the first time around, I thought to be on the ground the second time would be too normal a gesture. In between the two exhibitions (1997 and 2017) I had taught at Kunstakademie Münster, therefore knew the city pretty well including this dead end/one way channel where a lively atmosphere was always existent; on one side art studios, galleries, restaurants, bars etc.. on the other part more industry and offices.

Skulpture Projekte Münster, 2017 (Group) (Catalogue) (curated by Kasper König, Britta Peters, Marianne Wagner). Stadthafen 1, North side: Hafenweg 24, South side: Am Mittelhafen 20, Münster (Germany), 10.06. – 01.10.2017

Exhibited work: On Water, 2017

Site specific installation: ocean cargo containers, steel beams, steel grates, 6400 x 640 cm walkway

Photo Credit: Roman Mensing

As it is clear from the images I made a plan to make a bridge that goes under the water and connects these two shores that people experience the magic of walking on water and to have the miraculous and mystic image of people effortlessly standing on water.

Not only people of course, dogs, bicycles, ducks were also there. Some moms and dads were teaching swimming to their kids. People had the chance to chat on water. It became too popular always full of visitors. The walk on water was slow and thoughtful which made kind of ceremonial and somber at times.

Do you like for the public/audience to interact with your artworks? It feels in some instances such as in that the audience completes the artworks.

Yes, sometimes. In the case of “on Water” without the audience the work would have been invisible. The same goes for the work Shipped Ships where once people of Frankfurt were passengers in boats coming from Turkey,Italy and Japan. These two works and some more carried the risk of being unseen if not for the visitors.

“For some works lack of participants is not a problem. Mostly I like the audience to interact with works hoping they fulfil and feel my purposelessness.”

How influential is the audience’s perception of the themes you explore, to your work?

“I must say it is not very influential. I actually believe that the perception of the audience of the themes I explore should not be strong. I would rather give the audience something that they have not experienced before therefore their judgment as well as mine should not be accurate.”

You have explored the use of acrylic in your very first works (Yellow Plexiglas Sculpture, 1969, Istanbul). Why did you choose this material in particular? Which other techniques and media have you set in place to use?

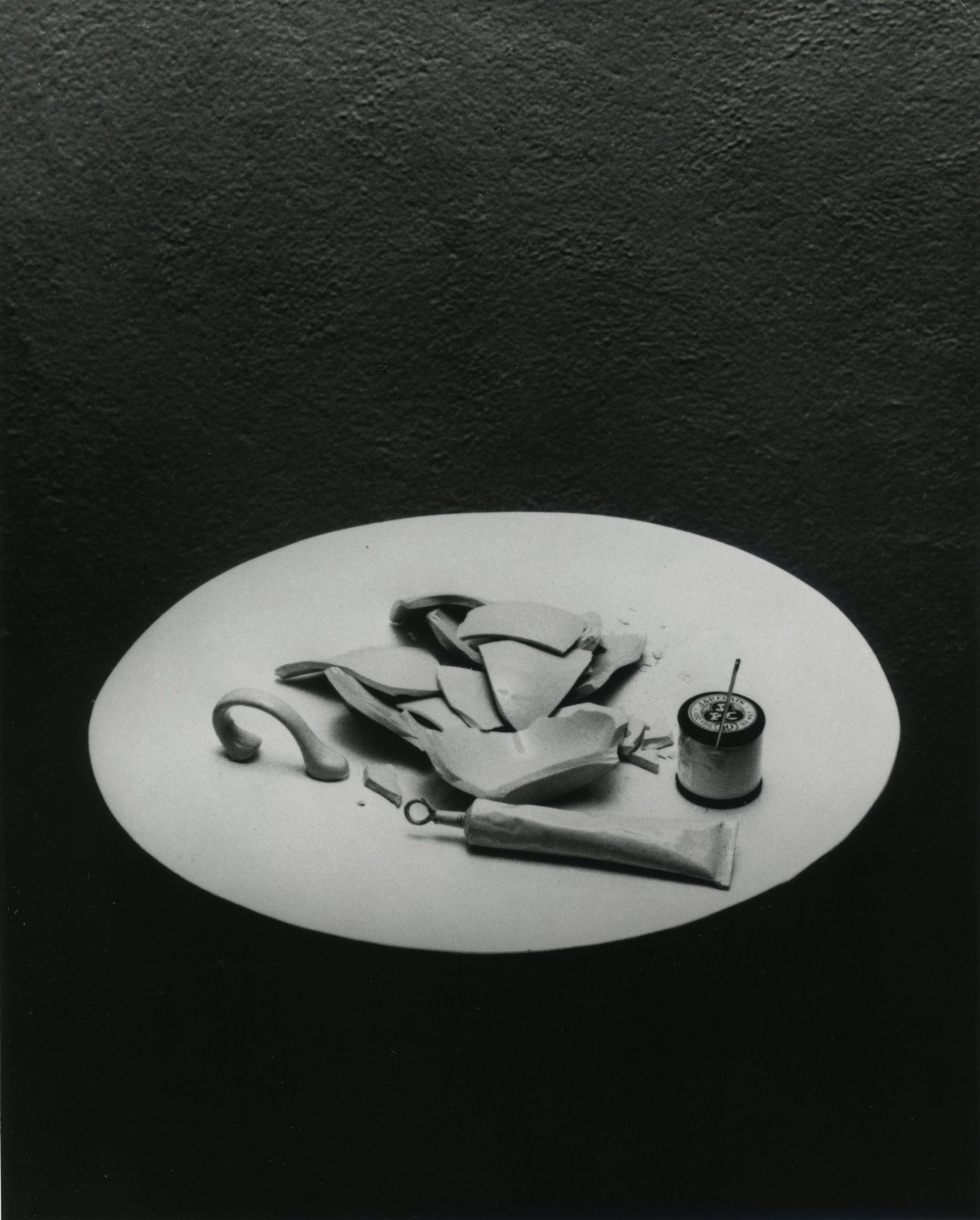

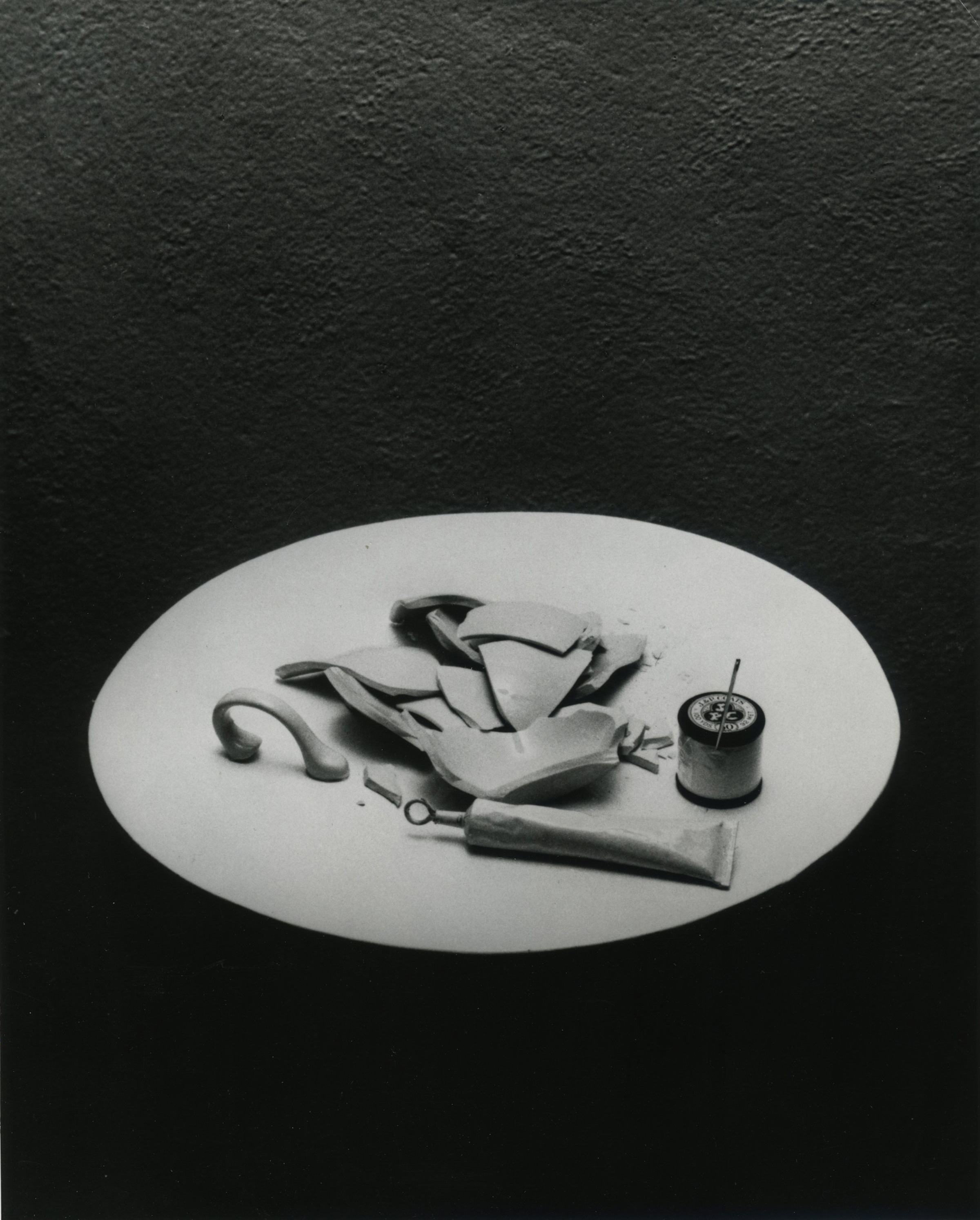

In 1969, I was a student of sculpture in the Academy of Art in Istanbul and I found these two pieces of plexiglass on the street. Plexiglass was for me a very advanced material at the time. I was fascinated. Without knowing much what I would do with them,I bent them and rolled them in a huge pot with hot water and placed one inside the other and participated in the school exhibition “New Tendencies” with this work. I placed it on the grass outside the exhibition room, maybe my first art in public space and to my surprise got the award of the exhibition with some money involved. This prize was not as important for me as these shiny plexiglass pieces. After the exhibition I recycled them to make other sculptures with the same hot water technique until the two plexi pieces broke down and disappeared.

I have great interest in material and have learned a lot from professionals who are experts on these materials. I like to work with professional people and I am mostly ready to change my forms according to their suggestions. Therefore I feel free to work in any media or technique as I wish or as my idea suggests.

What is your approach to form?

The same applies to form. I don’t have a strict or steady style. I have given myself the freedom to work in any material, style, or medium although I believe that I have a good feeling for form as I have had a very classical sculpture education for more than five years.

“I have learned a lot from one of my teachers Şadi Çalık who always said: ‘Forms should be outward rather than inward, as if they are hiding something inside, as if the inside is pushing from within’”

Kıpraşım / Ripple, 2017; Untitled sculptures, 2017. Site-specific installation, deconstructed plaster walls, revealed wooden walls; 19 aluminium sculptures: variable dimensions. Photo Credit: Hadiye Cangökçe.

He always thought that although we dont see the inside, the inside of a sculpture is as important as outside which meant one should give the same importance to parts that are invisible as the parts visible. This stayed with me and applies to everything in life, in my opinion.

Your body of work shows a dedication to long-term researched based projects. What is source material for new ideas? What books do you like?

I like fiction books. I also like lifestyle magazines to be informed of what is happening. I don’t watch tv these days. I watch a lot of films almost one every night some days. I love to go to cinema salons, even queuing for the ticket or popcorn is exciting for me but I am not doing it so much anymore because of the lazy comfort we have inside our homes now. I also sit on my own outside in a cafe and have coffee and watching the daily life. When I am involved in a project like on Water for example, I make lots of unnecessary research. I am not a research artist in the sense to display the outcome of research or knowledge as an art piece.

This issue’s theme is IN OUR WORLD. In your eyes, what does our world need less and more of?

I will have to give a very classical answer, maybe too much like a slogan but as it has high priority and urgency in these times when we cannot say “Our World” anymore like in earlier years :

“More peace, equality and justice, less discrimination, racism, less starvation.”

What are you working on at the moment?

I am very happy to be working on two permanent projects one for Japan/ Shikoku Island at the tip of a jetty and one for Istanbul right on the sea close to a shipyard from 15th century. The work in Shikoku island is almost ready, for the Istanbul one we will start working in August and will be ready for the 17th Istanbul biennial in September. I am excited for both as they will again happen on water.

Credits

Artworks · Courtesy of Ayşe Erkmen